Cambodia's Chinese marco

Zhou Daguan's visit to 13th century Khmer Empire produced the only surviving first-person account of the civilization that built Angkor Wat

In popular imagination, China is a place more to be explored than one that churns out explorers. Ancient stereotypes of the nation often still hold sway today: Mysterious, porcelain-skinned women; endless history; arcane religious practices and cruel torture methods.

Over the past 700 years, it is the account attributed to Marco Polo that has contributed most to this feeling of China as a place ripe for exploring.

Yet as this most celebrated of medieval explorers was said to have returned to Europe, sometime around 1275, ready to tell fantastical tales of his China travels, a lesser-known explorer left China to set down his own record of a strange and exotic land.

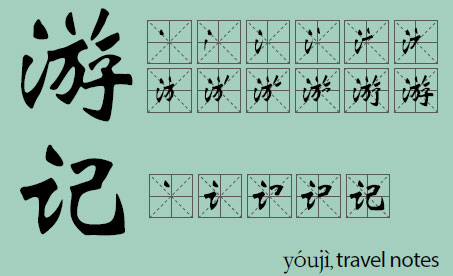

Zhou Daguan's (周达观) A Record of Cambodia: The Land and its People, (《真腊风土记》, sometimes translated more simply as The Customs of Cambodia) is the only surviving first-person account of the vast and powerful Khmer Empire (802-1431), which spanned Southeast Asia - the empire that built Angkor Wat, which today stands as one the most astounding pieces of religious architecture on the planet.

Aside from Zhou's account, there are little more than a smattering of temple carvings and inscriptions to help us understand this remarkable period of Khmer prominence, and as such his account is of great historical importance. Much of the history of the period taught in Cambodian schools today draws heavily on Zhou's account of the year he spent there from 1296 to 1297. A Record of Cambodia is fascinating insofar as it zigzags between detailed and occasionally bland reportage to the recording of spectacular myth and rumor, such as the Cambodian king's nightly lovemaking sessions with a nine-headed snake.

Unfortunately, very little is known of our obscure explorer. It appears he was an envoy in a delegation sent to Cambodia on behalf of Yuan Dynasty Emperor Temur Khan (元成宗) who ruled China between 1294 and 1307. The precise intention of this delegation is unclear, but it is likely that it was a diplomatic one with peaceful aims, Temur being less of a warmonger than his famously aggressive grandfather Kublai Khan.

Zhou was from Yongjia (modern Wenzhou), a prosperous port city in transition (only having recently fallen to Mongol invaders) and inhabited by traders, soldiers, Muslims and migrants, among others, all of which should have contributed to an outward-looking nature on Zhou's part. However, this is not always evident, and Zhou's sheer sense of Chineseness brought heavily to bear in the book, not to mention comments often instilled with an innate sense of superiority. But perhaps such thoughts are understandable - it is likely that Zhou, as an educated Chinese, believed that China was the absolute center of the civilized universe, in much the same way that British colonialists several centuries later believed that "God was surely an Englishman".

As translator Peter Harris notes in his introduction: "Zhou is an observant traveler, but his writings bear the hallmark of a Chinese traveler abroad, with their condescension, sometimes prurient interest in erotica, and earnest efforts to tabulate, elucidate and observe exotica in language that people back home will enjoy. These qualities are typical of other imperial travelers."

And so it is that even with something as simple as chapter titles that Zhou's intensely Chinese worldview shines through. Chapter 5 sees Zhou writing about various holy men and monks in Cambodia and is titled The Three Doctrines. While the three doctrines (Daoism, Buddhism and Confucianism) are the main strands of thought that have underlined Chinese philosophical traditions for the best part of two millennia, the only one that could have had any significance in Cambodia in 1296 was Buddhism.

The Khmer Empire was a confused mix of Buddhist and Hindu beliefs, yet throughout the book Zhou consistently refers to what were, almost certainly, Hindu priests as Daoists. It is unclear if his refusal to look at religion in Cambodia through anything, other than a three-doctrine lens is through reverence to "the sacred dynasty", sheer bloody-mindedness, or simply a lack of belief that anything could exist outside of the three teachings.

Another notable chapter is Salt, Vinegar and Soy Sauce. In it Zhou writes: "They do not know how to make soy sauce, either. This is because they have no soybeans or wheat, and have never made a fermenting agent." That chapter is partly dedicated to a condiment that didn't even exist in Cambodia and attests to how much its absence was felt by the Chinese adventurer. No doubt similar disappointment faces many Chinese travelers in foreign lands today.

Although Zhou diligently logs the food, flora, animals and buildings of ancient Cambodia, it is invariably the points where a travelogue turns to the esoteric, strange, cruel, sexual and previously unseen that it truly begins to fire the imagination. With young Zhou (he was probably in his 20s at the time of writing) there is no lack of this. Perhaps the most unusual practice to grab Zhou's is zhentan, a ceremony that supposedly involves all the young girls in Cambodia (between the ages of 7 and 11) being deflowered by Buddhist monks or Hindu holy men. What jars and horrifies the modern reader is actually presented as a deeply auspicious occasion, but exactly why these girls needed to lose their virginity before marriage in this way is unclear; it is possibly apocryphal.

Such is his indignation that Zhou even finds time to do a little bit of moralizing on the gay prostitution scene: "There are a lot of effeminate men in the country who go round the markets every day in groups of a dozen or so. They frequently solicit the attentions of Chinese in return for generous gifts. It is shameful and it is wicked."

As any modern-day backpacker knows, traveling for any length of time inevitably leads to a gamut of conversations about toilets and toilet habits. The 13th century was no different, with Zhou not afraid to get his hands dirty: "Whenever they go to the lavatory they always go and wash themselves in a pond afterward. ... When they see a Chinese going to the lavatory and wiping himself with paper they all laugh at him, to the point where they don't want him in their home. Among the women there are some who urinate standing up - and that is really funny."

Zhou has a point here: It is pretty funny. Today, water is still preferred over paper in Cambodia - toilets come equipped with small pistols that blast water with varying degrees of power, aka bum guns or toilet hoses, akin to the bidet in many parts of the world.

In his book, Cambodia's Curse: The Modern History of a Troubled Land, Pulitzer-winning journalist Joel Brinkley relentlessly drives home the refrain that today, so many Cambodians live "more or less as they did 1,000 years ago". If you ask expats in Cambodia why they choose to live in Cambodia, their answers take on a similar hue: The tropical weather, the simplicity of living, the lure of the women, to live an easily life.

As Zhou said seven centuries ago: "Chinese sailors do well by the fact that in this country you can go without clothes, food is easy to come by, women are easy to get, housing is easy to deal with, it is easy to make do with a few utensils, and it is easy to do trade. They often run away here."

Some things, seemingly, never change.

Courtesy of The World of Chinese, www.theworldofchinese.com

The World of Chinese

(China Daily European Weekly 08/07/2015 page27)

Today's Top News

- US tariffs deepen Asia's uncertainty

- Mini landscapes drive village's economy

- Nation sees consumption boom during Spring Festival holiday

- Milan-Cortina Winter Olympics closes as China posts best-ever overseas result

- Iowa friends salute warm ties with Xi

- Berlin and Beijing: Charting a course for stability and green growth