Education, charity and beauty of bouquets

A Chinese property baron sets off a debate about the worthiness of charity recipients

Philanthropy is generally not a hotbed for controversies. But here in China you are watched closely if you hold your purse string tight or let your money flow and, in the latest case, where it flows.

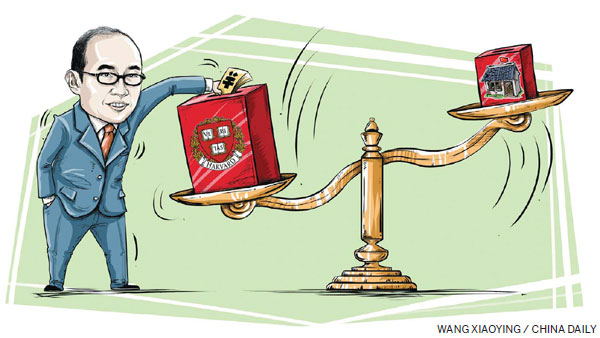

Pan Shiyi, a real estate tycoon who is a celebrity in his own right, ruffled feathers when he and his wife decided to donate $15 million to Harvard University.

The grapevine news that hit the nerve center was more dramatic: It said Pan gave $100 million. Later he clarified that he planned to set up a fund with a total of $100 million, of which $15 million is earmarked for Harvard, and specifically for needy students from China. Other schools being considered include Yale and other US and British universities of prestige.

Yao Shujie, a Chinese economist, spoke for many when he questioned Pan's motives. "Pan made his fortune from the property market in China. Why should he go all the way to the US for philanthropy? He forgot where his roots are."

Others suggested that Pan's donation was an effort to win admission for his son into the Boston school. Their rationale: the benchmark set by Pan for recipients' eligibility is 65,000 yuan in annual family income, which most middle-class Chinese families can easily cross and, therefore, not many from China will meet this requirement anyway.

Now, Pan is no Chen Guangbiao, who goes around trumpeting his altruistic deeds. He has dabbled in entertainment, even playing the male lead in a feature film. He does have a much higher profile than most businessmen in China, but he earned it not from his business feats, but rather from his microblog comments on public affairs.

As a matter of principle, Pan has the right to donate to whichever individual or organization he sees fit. It is none of outsiders' concern whether the recipient is Chinese or foreign. Every person has his or her own priorities when it comes to choosing a target for help.

Most Chinese now totally get this. Had this happened a decade or two ago, public feedback would have been predominantly negative, I'm certain, because most would have equated such an act with a lack of patriotism. This feeling still lingers, but it is shared by fewer and fewer people as the public can more easily find the distinction between public rights and private ones.

A few years ago, Zhang Lei, a Chinese financier, donated $8.88 million to Yale University, his alma mater. Had he been better known, he would have borne the brunt of a major ill-will campaign.

Detractors, for all their misplaced zeal to dictate private citizens' choice of charity, do apply a crude principle of economics when they see something like that. For a school like Harvard, they reason, this money is just icing on the cake. It has got so many donors that Pan's money would not yield the highest return on investment, if it's seen as an investment.

Ordinary Chinese do not use calculus to figure out which school needs donations the most, but we do have two colorful sayings that correspond to the rule of microeconomics: Adding flowers to a big bouquet or sending charcoal to someone trapped in snow. You get more bang for your buck if you do the latter, but that will require independent thinking.

Most investors, professional or otherwise, would follow the herd mentality and chase objects everyone else is already hotly pursuing. You would feel you have rubbed off some of the glitter if you give money to Harvard in the US or Tsinghua University in China. In fact, the top universities in China get proportionately much more in both private donations and public funding. They are the largest, most prominent bouquets in the garden of higher education, and throwing roses or petals at them would probably yield more psychological returns than tangible ones.

By this yardstick, the problem with charity recipients is not their nationality, but rather which one is in dire need of such help. Harvard may have a much larger budget than Tsinghua, which, in turn, is much better funded than a regular college in China. The ones most worthy of such financial assistance, as the logic goes, are those located in poverty stricken areas that cater to the lowest-income families.

As I gather from empirical evidence, this social stratum is given short shrift and deserves a strong and consistent inflow of funding. Education, if it be the great equalizer, should give these students from underprivileged families equal opportunities so that they can make a fresh start with their lives. But philanthropy alone is unable to solve this problem. It has to be from the state, which is implementing all kinds of programs for that purpose but still leaves much for improvement.

A year ago, a photo surfaced online of a father carrying a desk to school for his daughter. It outraged the country. Shouldn't this be the responsibility of the local education authority, not the parents? Only in those areas not covered by the state can philanthropists fill the void, so to speak.

There are many grassroots programs. The one for the free lunch is especially touching as it funds students who can hardly pay for their meals. The money enables them to eat slightly better and consume more nutrients when their body needs them most.

One can question which is a better economic choice: a large sum for a world-renowned institution or a similar sum that may benefit tens of millions of hinterland children. If you push the argument further, you will realize that there are even youngsters who suffer from worse poverty and misery. They may not be in a country you are familiar with, but the same amount of money may be able to make a greater difference in their lives than in a Chinese backwater region.

However, that is just one way of calculating the worthiness of a recipient. You can also use a different gauge and see how much money is wasted in overheads or unnecessary expenses. And you may choose a recipient that is best managed and yields the least waste in the process.

Then there is the possibility of using philanthropy as a public relations tactic - to smooth the wrinkles of business dealings or boost one's personal image. If handled deftly, such a fusion of business and non-business strategies would not raise eyebrows. If Chinese businesses have an eye for the global market, why not non-business affairs such as charities? Shouldn't one expand his or her horizon to that of the whole world?

I don't want to second-guess Pan Shiyi's motives behind his decision to fund Ivy League-bound Chinese students. He has donated many times to poor children in Chinese interior provinces. He may see the new move as helping those on the tip of success and the schools as incubators for tomorrow's leaders. Zhang Xin, Pan's wife, says: "I want the best students to receive the best education regardless of whether their families can fund it."

The writer is editor-at-large of China Daily. Contact him at raymondzhou@chinadaily.com.cn

(China Daily Africa Weekly 08/01/2014 page30)

Today's Top News

- China reports 5% GDP growth in 2025

- Sanya rises as magnet for Russian tourists

- China's steady opening-up for Asia-Pacific economic growth

- Blueprint seen as a boon for entire world

- 'Kill line' an inevitable outcome of US system

- Fusion energy drive entering a decisive phase