Remarkable propensity for violence

| Wang Baoqiang (right) plays a migrant worker-turned-thief in A Touch of Sin. Provided to China Daily |

Maverick director's new film pulls no punches as it depicts harsh realities of working class

Violence happens all the time in cinema. Whether Optimus Prime is mutilating the robotic innards of Decepticons with his bare fists, or Alfred Hitchcock is having Janet Leigh stabbed off screen in a shower, violence adds easily understood and entertaining tension to cinema.

What better way to resolve a conflict or begin the narrative tension that keeps us locked to our seats for two hours. As such, cinematic violence is a frequently used narrative technique in the director's arsenal, particularly as an affirmation of agency, of a character's power. Cinematic violence represents the assertion of intent to control a person or a situation.

Violence is so prevalent in modern cinema that we sometimes forget to acknowledge its existence. In Jia Zhangke's latest film, A Touch of Sin, violence is the ultimate and final manifestation of causality; it makes a frighteningly psychological and clear socioeconomic portrait of the Chinese masses.

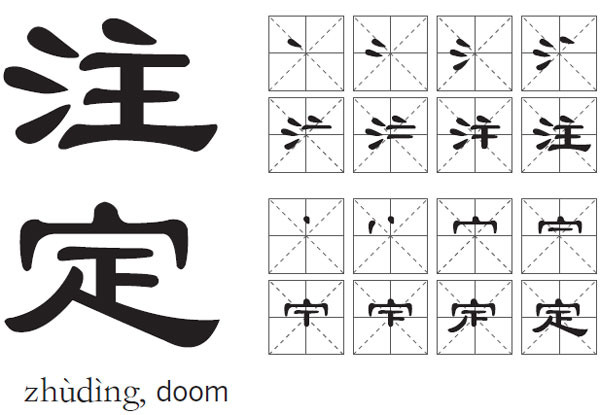

A Touch of Sin (天注定,tiān zhùdìng) is one of a series in Jia's recurring dystopian and bitter visions of everyday China. Broken into four story arcs, it chronicles the descent of four unrelated characters into a pit of desperation as they deal with recurring themes of corruption, vice and bureaucracy. While these characters seem to share very little in terms of identity, socioeconomic background or even geographic location, they all ultimately resort to violence as a final act of desperation: a miner (Jiang Wu), an exploited young man (Wang Baoqiang), a receptionist (Zhao Tao) and a migrant worker (Luo Lanshan).

Despite being spread out across the country, their growing resentment and disillusionment with modern Chinese society seems not only to be a rejection of “the Chinese dream” but also a frightening insight into the downward-spiraling morale of China's desperate and downtrodden.

It was cleared for release in China in December but since debuting at the Cannes Film Festival last May, where Jia won the award for best screenplay, its mainland release has been in limbo.

Dahai (miner): Chief, when you sold off the coal mine you promised yearly dividends.

Cūnzhǎng, cūnli méikuàng chéngbāogěi cáituán de shíhou, shuō hǎo le měinián dōuyǒu fēnhóng de.

村长,村里煤矿承包给财团的时候,说好了每年都有分红的。

Village chief: Let's talk about it in private.

Sīxià shuō ba.

私下说吧。

Dahai: If you don't talk to me, I will make sure you talk to the Central Discipline Inspection Commission of the CPC.

Nǐ bù gēn wǒ shuō, dào shíhou jiù gēn Zhōngjìwěi de rén shuō.

你不跟我说,到时候就跟中纪委的人说。

It is the use of ultra-violent Tarantino-esque brutality that sets this film apart from Jia's previous work.

Blood spurts in fountains; there's murder by shotgun, axe, kitchen knife and hammer. Each of the protagonists finally resorts to violence to cope with the hopelessness of their respective situations, stemming from their oppressive backgrounds and poverty.

The miner hopelessly looking to extract promised payment from corrupt local officials, the abused receptionist looking for a way out, the migrant worker searching for another job, and the exploited young man all face repression.

While it seems nearly every character in A Touch of Sin displays a remarkable propensity for violence, Jia clearly establishes a normal level of brutality, whereupon each protagonist is shown descending into abnormally violent tendencies, correlating with their rising frustration and anger.

The opening sequence of the film sees Wang Baoqiang being ambushed by a group of men.

Under any other circumstance, this might be a scene from Mad Max - a post-apocalyptic highway robbery by axe.

In fact, this is modern China. Without flinching, he dispatches them with a pistol - coldly and efficiently.

Wife: I got two remittances, 130,000 RMB altogether.

Shōudào guò liǎng bǐ qián, yīgòng shísān wàn.

收到过两笔钱,一共十三万。

San'r (migrant worker turned robber): That's right.

Nà jiù duì le.

那就对了。

Wife: I don't want your money.

Wǒ búyào nǐ de qián.

我不要你的钱。

A Touch of Sin is brutal and calculated in exacting violence, the one thing its everyday protagonists are able to establish their agency in the face of an overwhelmingly ignorant system. The film appears to be a brutally dystopian vision of how helplessly China's working class continues to bear the brunt of a system that is increasingly ignorant of their needs. What's even sadder is these visions are far from dystopian fantasies. One only has to put an ear to the ground to hear the stories of murder in the Chinese countryside to understand the dynamics Jia is portraying.

A Touch of Sin, then, is not only a violent work of fiction, but a voice for those who used their last ounce of agency to show us the absurdity of the modern condition.

Courtesy of The World of Chinese, www.theworldofchinese.com

The World of Chinese

(China Daily Africa Weekly 04/11/2014 page27)

Today's Top News

- Year of the Horse carries message of resilience, solidarity, industriousness

- China remains anchor of stability in unsettled world

- Stage beckons, festive spirit resonates overseas

- China predicts over 285 million inter-regional trips on first day of Spring Festival holiday

- China extends visa-free policy to Canada, UK

- 2nd round of Iran-US talks to be held in Geneva Tuesday