Science and Health

Scientists grapple with looming volcanic question

By Duan Yan (China Daily)

Updated: 2011-05-24 08:06

|

Large Medium Small |

Geologists step up monitoring following recent eruptions, Duan Yan reports from Jilin province.

Changbai Mountain, on the border of China and the Democratic People's Republic of Korea (DPRK), is a popular tourist destination and the eggs boiled in the steaming water of nearby hot springs are a key attraction.

|

|

Zhong Guangpei (left) and Su Xiaoyi, two staff members at Changbaishan Tianchi Volcano Observatory, measure the temperature of a hot spring on Changbai Mountain to monitor the volcano's activity. Zhang Tao / China Daily |

Geologists are also interested in the hot springs, but not for eggs.

The 2,744-meter-high volcano is China's least stable. Geologists are closely monitoring it following the earthquake that hit Japan on March 11 and increasing volcanic eruptions around the world.

Iceland's most active volcano, Grimsvotn, erupted on Saturday, hurling a plume of ash and smoke that is approaching northern Scotland.

Mount Shinmoedake in Japan erupted three times, on March 13 and April 8 and 18. Southern Italy's Mount Etna erupted on May 12, and the Philippines has raised its alert level as the Taal volcano rumbles.

Volcanoes are well studied in those countries but less so in China, which has had no volcano disasters in its recent history. More than 10 volcanoes are considered active, and six of them are monitored.

Now experts are proposing a major update of the monitoring system and collaborative research with DPRK so China can prepare for any volcanic disasters that might come.

"Right now, close monitoring is crucial," said Liu Jiaqi, a professor in the Institute of Geology and Geophysics at the Chinese Academy of Sciences. He explained that volcanoes in Japan are more active because they lie in what is called a subduction zone, where the Pacific plate slides under other plates. Changbai lies on the Eurasia plate.

The energy created in the subduction process creates earthquakes and turns rock into magma, which rises as lava to form volcanoes. This happens around the edge of the Pacific Ocean in what has been called the Ring of Fire.

"We need to pay special attention to it," Liu said.

Last June, the Chosun Ilbo newspaper in the Republic of Korea (ROK) reported that South Korean geologist Yoon Sung-hyo, who has been researching Changbai with Liu and other Chinese experts, said there were "clear signs" that Changbai was heading toward an eruption. He expected it to happen in 2014 or 2015.

Chinese experts discounted the threat, saying the eruption does not seem imminent. Since being in an active phase from 2002 to 2005, the volcano seems to have quieted down, although scientists expect more activity in the next few years.

"The only sure thing is that the eruption will not happen anytime soon," Liu said. "But as to when it will erupt, and what forms the eruption will be like, accurate conclusions can only be made through more monitoring as well as research."

What to expect

|

|

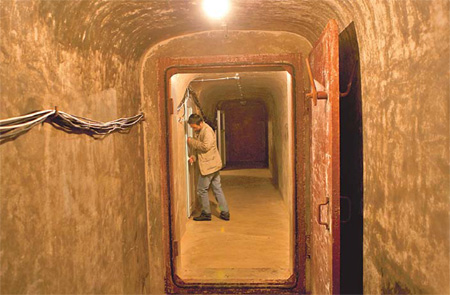

Zhong Guangpei checks cables linking monitoring equipment to make sure the data will be transmitted. Zhang Tao / China Daily |

Geologists are much more certain about the consequences of an eruption. "Just the water of Tianchi Lake all coming down from the mountaintop will be devastating," said Xu Jiandong, director of the China Earthquake Administration's Active Volcano Research Center in Beijing.

Tianchi Lake has a surface area of 9.8 square kilometers, roughly the size of 22 Tian'anmen Squares. It was formed during a massive eruption about 1,000 years ago and is one of the highest crater lakes in the world. It holds 2 billion cubic meters of water.

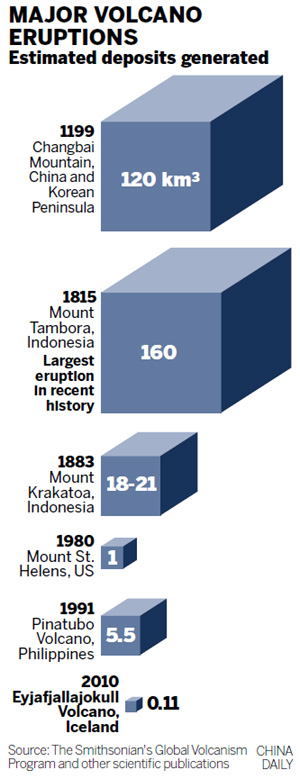

Liu Ruoxing, one of China's leading volcanologists and former director of the Institute of Geology at China Earthquake Administration, estimated that the violent, explosive eruption occurred around 1199 or 1200. The volcano spewed up to 120 cubic kilometers of magma (molten rock) and tephra (ash) and the eruption is considered one of the most powerful in the past 2,000 years.

"Japanese geologists have discovered that eruption dumped ash as far as northern Hokkaido," 1,000 km away, Xu said.

And unlike a thousand years ago when the area was sparsely populated, Changbai Mountain is home to about 100,000 people on its north and west slopes, and is a major draw for tourists. Hotels and residential compounds are being built. Even the observation centers provide accommodations for tourists.

Taking notes

Zhong Guangpei and Su Xiaoyi, two staff members at Changbaishan Tianchi Volcano Observatory, walked through the crowds of tourists, climbed over the fence and tiptoed through soft ground to a shallow spring spot below the wooden sidewalk.

Zhong took a thermometer from a black suitcase and pushed the metal rod into the soil under the water. Curious tourists watched from the sidewalk, and one asked Zhong if it was OK to touch the water.

"You'd better not. It's around 80 degree Celsius, hot enough to boil eggs," Zhong said. "The temperature is always the same, no matter in summer or winter. "

After he measured the temperature, Su took out a glass container and captured the gases bubbling from the hot spring. "Any changes in the temperature or contents of gas samples indicate the volcano's underground activities," Zhong said. He explained that carbon dioxide is the dominant gas. Other elements, including nitrogen, helium and hydrogen, may appear at different levels when volcanic activity increases.

Regular monitoring of Changbai started in 1999, and data collection at this site is repeated every three days. Similar sampling and measuring at four other hot springs on the north and west slopes are carried out periodically when weather and other conditions permit.

Yang Qingfu, director of the earthquake and volcano analysis and forecast center at the seismology bureau of Jilin province, said the temperature of the hot springs indicates what's going on underground and can be a predictor of eruptions. "These data showed the volcano was stable and there were no signs of an imminent eruption," Yang said. But they aren't enough, he said. "We have 11 observatories, but not all stations can carry out real-time monitoring."

On the screen of a monitoring computer at Tianchi Observatory on the mountain, Zhong pointed out six red dots that indicated six observatories were sending in current seismic data. "These data are also sent to the seismology bureau of Jilin province in Changchun and to the China Earthquake Administration in Beijing," Zhong said.

Above the Tianchi station, Zhong and his colleagues had to wade through knee-high snow before he could check on the power cords of a seismic monitor that is set into a cave and locked behind four iron doors. Other observation points and hot springs are even more remote.

"These tasks can only be conducted when the snow has melted away," said Wu Chengzhi, an engineer at the Changbaishan Volcano Observatory at the base of the mountain's north slope.

Every summer, Wu and other staff members pack their bags and enter the forests, living in tents for days before they can reach other observatories to retrieve seismic data and hot springs to analyze temperatures and gas content. "We have to watch out for snakes sneaking into the tents," Wu said.

Yang said newer monitoring equipment, more stable power cords and cables, and more observatories would provide real-time data and not require staff to trek through forests and snowfields.

| 分享按钮 |