Global General

Humble soldier adjusts to fame

By Sharon Cohen (China Daily)

Updated: 2011-01-04 08:10

|

Large Medium Small |

|

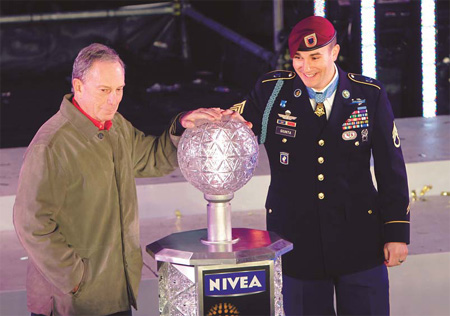

Medal of Honor recipient Staff Sergeant Salvatore Giunta (right) and New York City Mayor Michael Bloomberg prepare to start the countdown to midnight on New Year's Eve in Times Square, New York, on Friday. Seth Wenig / Associated Press |

CHICAGO - It was years in the making, so Staff Sergeant Sal Giunta had time to talk with his wife about the "what if" question. He'd been recommended for the Medal of Honor, the nation's highest military decoration. If chosen, his name would be in headlines. His face in the spotlight. He'd be a celebrity.

And again and again, he'd have to tell strangers the harrowing story of a deadly ambush in Afghanistan.

"He was worried," says Giunta's wife, Jenny. "He didn't know how he was going (to be) able to talk to people about it. He couldn't even talk to me. He didn't even talk to his parents about it. How was he going to talk to the world about it? How was he going to be OK with telling his story?"

Giunta did receive the medal. And, as expected, he's become a celebrity with all the trappings: A celebration at the White House. Praise from the president. Late-night TV appearances. Invitations galore. And calls, too, for him to tell his story - a story that forever changed his life.

Through it all, Sal Giunta has remained a humble man in a "look at me" world, quickly adjusting to his newfound fame, insisting he's just an average soldier. The gold, five-point star draped around his neck says otherwise: He's the first living recipient of the Medal of Honor for service in Afghanistan and Iraq - and the first for actions since Vietnam. The 25-year-old soldier would have you believe there's nothing special about braving rocket-propelled grenades, machine guns and a wall of bullets to help one comrade, then free another from the clutches of the Taliban.

"I'm not a very smart guy," he recently told a crowd gathered to see him at an armory outside of Chicago. "I haven't guided myself to the position I'm in. I've been mentored. I've been tutored. I've been taught along the way. I've been told to follow. I've been told to lead."

Everywhere he goes, on publicity tours organized by the Army, Giunta portrays himself as an everyman, not a superman. That hasn't stopped football and hockey fans from giving him standing ovations, crowds from lining up for photos, strangers from embracing him.

"This isn't me," Giunta said in an interview. "As far as getting used to it, I don't think I ever will."

Since he received the medal in mid-November, Giunta has come to realize that instant fame brings opportunities, pressures and surreal moments. His choice of lunch - an Italian beef sandwich - now turns up in a gossip column. His mere presence in public is applauded.

Giunta casts himself as an ambassador for everyone in uniform. Modestly, of course: "I'm representing so many people that I know for a fact are faster than me, smarter than me, stronger than me, braver than I am," he says.

He knows, though, he's the star attraction, the reason crowds come out on a bitter winter morning, the reason he's sitting before a microphone on an afternoon radio show. It's his story they still want to hear - and telling it doesn't get any easier. "I've never seen anyone else asked what was the worst day in your life and let's break it down piece by piece and please go into detail," he says. "For some reason they continually ask me every single day and multiple times a day. Of course, it's difficult. I lost two very good friends that day. They mean absolutely everything (to me) and people brush by their names. And they keep saying 'Giunta. Staff Sergeant Giunta.' That doesn't feel right."

The dead were Sergeant Josh Brennan and Specialist Hugo Mendoza. Both were on the mission with Giunta as part of Company B, 2nd Battalion (Airborne), 503rd Infantry Regiment.

Giunta was tight with Brennan; they trained together and traveled around Italy, where they were based. "He was athletic, smart, funny, always someone you could count on," he says. As for Mendoza, a medic: "He truly cared about other people more than he did about himself."

It was a moonlit night on Oct 25, 2007, when enemy forces formed an L-shaped ambush around Giunta's platoon in the Korengal Valley in eastern Afghanistan, a dangerous strip of land that served as a key route for al-Qaida to move weapons, fighters and money from Pakistan. Brennan and another soldier were hit first. When Staff Sergeant Erick Gallardo ran through an open area to link up with them, he was stopped by a barrage of gunfire. Moving toward Giunta, he was struck, a round from an AK-47 dinging off his helmet and temporarily disorienting him.

Giunta jumped up, exposing himself to rockets and enemy fire, to help Gallardo. One bullet then smashed into Giunta's armor - pushing him back. Another shattered the weapon slung across his back.

He didn't stop.

Giunta and his comrades regrouped, throwing grenades and charging forward. When Giunta, who was a rifle team leader, realized Brennan was missing, he raced ahead and saw two insurgents carrying the wounded sergeant by his arms and legs.

Giunta, alone and without cover, shot and killed one of the insurgents; the other ran away. Giunta dragged Brennan by the vest to safety. He tried to stop the bleeding, tried to comfort his friend. Someday, Giunta told the mortally wounded soldier, he'd be telling hero stories.

Why did Giunta do it? He said it was the logical next step, but in a recent Army interview, Gallardo said Giunta simply wanted to save his buddy. Brennan "would have done the same thing for me", he quoted Giunta as saying.

Gallardo says he told Giunta: "You don't understand ... but what you did was pretty crazy. We were outnumbered. You stopped the fight. You stopped them from taking a soldier."

"Unbelievable what he did that night," Gallardo added. "I know he's going to hate me for saying this, but he's the face of the war now."

Associated Press