Global General

Lebanese artist fights for right to sing

(China Daily)

Updated: 2010-07-31 09:46

|

Large Medium Small |

BEIRUT - Across four decades, Fairouz's songs of freedom, justice and love transfixed Arab audiences, moved millions to tears and gave hope to the Lebanese during the darkest days of their 15-year civil war.

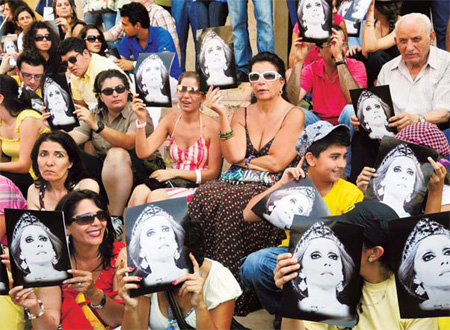

Fans of Lebanese diva Fairouz hold her pictures as they protest against a ban preventing her from performing songs composed by "The Rahbani Brothers" in Beirut, Lebanon. Ahmad Omar / Associated Press |

At 75, the Lebanese singer still performed, seemingly impervious to age - until now, when a fight over royalties within the Arab world's most famous musical family threatens to silence Lebanon's most beloved diva.

The fans are outraged.

It is a familiar story the world over - heirs fighting over an inheritance - but in this case it involves a cultural icon whose songs changed the musical landscape of the Arab world.

The Rahbani family quarrel is being played out on newspaper pages and tabloids in the region, angering many for whom Fairouz is an untouchable figure.

"If it was someone else we might have talked about who's right or wrong and what the law says, but not in this case because Fairouz is not an ordinary person," said Egyptian film star Elham Shahine, who took part in a demonstration in Beirut Monday calling on Fairouz to keep singing.

"Fairouz is above all laws," she added.

Most of Fairouz's songs were penned by her late husband, Assi Rahbani, and his brother Mansour, together known as "The Rahbani Brothers", and now her nephews are accusing her of not asking their permission to sing that repertoire or paying them the necessary royalties.

Assi died in 1986 and when Mansour passed away in January 2009, the long simmering family dispute boiled over.

This summer, Fairouz had planned to perform at the Casino du Liban Ya'ish Ya'ish (Long Live, Long Live), a 1970 musical written by the Rahbani brothers. But her nephews sent a letter to the Casino's administration reminding them that such a performance would require the approval of the heirs.

Mansour's sons - Marwan, Ghadi and Oussama - decline to say how much money is owed, but they are demanding remuneration for each time the diva performs songs or any of the musical plays from the Rahbani repertoire.

"All what we are asking for is our intellectual property rights and this is something we will not give up," Oussama, also a musician, told The Associated Press.

He accused Fairouz of trying to wipe out Mansour's name from the Rahbani brothers' legacy.

"We love her and want her to sing, but if she - the symbol of Lebanon and the Rahbani family - is not going to protect the intellectual property rights of the Rahbani brothers, who will?" he asked.

Oussama says the late Mansour had reached a "gentleman's agreement" with Fairouz over several performances she made when he was alive. But he cited two instances in 2008, when she performed in Damascus and in Sharjah and did not pay.

Rima Rahbani, a director and the daughter of Fairouz and Assi, accused the heirs of greed and said there was no formal system of direct payments to the brothers from Fairouz herself.

In a telephone interview with AP, she said Mansour's heirs should collect their money from Sacem, a Paris-based organization whose job is to collect royalty payments and redistribute them to the original authors.

Mansour had joined Sacem in 1963.

"Sacem should collect the fees from the producers, not from Fairouz, and after the performances are made, not before," she said.