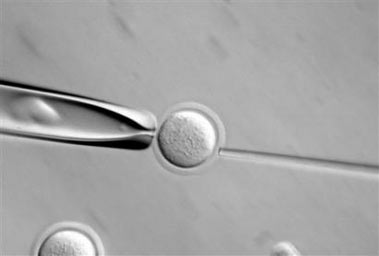

In this

image provided by Harvard University, graduate student Jacqueline Rosains

works with mouse embryonic stem cells, performing a nuclear transfer

between the cells, date unknown in Cambridge, Mass. [AP

Photo] |

Stepping into a research area marked by controversy and fraud, Harvard

University scientists said Tuesday they are trying to clone human embryos to

create stem cells they hope can be used one day to help conquer a host of

diseases.

"We are convinced that work with embryonic stem cells holds enormous

promise," said Harvard provost Dr. Steven Hyman.

The privately funded work is aimed at devising treatments for such ailments

as diabetes, Lou Gehrig's disease, sickle-cell anemia and leukemia. Harvard is

only the second American university to announce its venture into the

challenging, politically charged research field.

The University of California, San Francisco, began efforts at embryo cloning

a few years ago, only to lose a top scientist to England. It has since resumed

its work but is not as far along as experiments already under way by the Harvard

group.

A company, Advanced Cell Technology Inc. of Alameda, Calif., is trying to

restart its embryo cloning efforts. And British scientists said last year that

they had cloned a human embryo, though without extracting stem cells.

Scientists have long held out the hope of "therapeutic cloning" against

diseases like diabetes, Parkinson's disease and spinal cord injury. But such

work has run into ethical objections, a ban on federal funding and the

embarrassment of a spectacular scandal in South Korea.

Now, using private money to get around the federal financing ban, the Harvard

researchers are joining the international effort to produce stem cells from

cloned human embryos.

"We're in the forefront of this science and in some ways we're setting the

bar for the rest of the world," said Dr. Leonard Zon of the Harvard Stem Cell

Institute.

Dr. George Daley of Children's Hospital Boston, a Harvard teaching hospital,

said his lab has begun its experiments. He declined to describe the results so

far, saying the work is in very early stages.

Two other members of the Harvard Stem Cell Institute, Douglas Melton and

Kevin Eggan, have also received permission from a series of review boards to

begin human embryo cloning, the institute announced.

Daley's work is aimed at eventually creating cells that can be used to treat

people with such blood diseases as sickle-cell anemia and leukemia. Melton and

Eggan plan to focus on diabetes and neurodegenerative disorders like Lou

Gehrig's disease, striving to produce cells that can be studied in the lab to

understand those disorders.

"We think that this research is very important, very promising, and we

applaud Harvard for taking the initiative to move this work forward," said Sean

Tipton, president of the Coalition for the Advancement of Medical Research,

which supports cloning to produce stem cells.

Cloning an embryo means taking DNA from a person and inserting it into an

egg, which is then grown for about five days until it is an early embryo, a

hollow ball of cells smaller than a grain of sand. Stem cells can then be

recovered from the interior, and spurred to give rise to specialized cells or

tissues that carry the DNA of the donor.

So this material could be transplanted back into the donor without fear of

rejection, perhaps after the disease-promoting defects in the DNA have been

fixed. That strategy may someday be useful for treating diseases, though Daley

said its use in blood diseases may be a decade or more away.

Daley's current research is using unfertilized eggs from an in-vitro

fertilization clinic and DNA from embryos that were unable to produce a

pregnancy. Both are byproducts of the IVF process and should provide a ready

supply of material for research, Daley said in a statement. Later, his team

hopes to use newly harvested eggs and DNA from patients.

Eggan said he and Melton will collaborate on work that uses DNA from skin

cells of diabetes patients and eggs donated by women who will be reimbursed for

expenses but not otherwise paid.

Harvesting stem cells destroys the embryo, one reason that therapeutic

cloning has sparked ethical concerns. The Rev. Tad Pacholczyk, director of

education for the National Catholic Bioethics Center in Philadelphia, said he

found the Harvard developments troubling.

By cloning human embryos to extract stem cells, he said, "you are creating

life precisely to destroy it. You are making young humans simply to strip-mine

them for their desired cells and parts. And that is at root a fundamentally

immoral project that cannot be made moral, no matter how desirable the cells

might be that would be procured."

Apart from the controversy, human embryo cloning has also been the subject of

a gigantic fraud.

Hwang Woo-suk of Seoul National University in South Korea caused a sensation

in February 2004 he and colleagues claimed to be the first to clone a human

embryo and recover stem cells from it. He hit the headlines again in May of last

year when he said his lab had created 11 lines of embryonic stem cells

genetically matched to human patients.

But the promise came crashing down last December and January when Hwang's

university concluded that both announcements were bogus.