Courtroom rules in military trials of terrorist suspects came into question

Tuesday during a pretrial hearing for a suspected al-Qaida member charged in a

March 2002 grenade attack that wounded three journalists in Afghanistan.

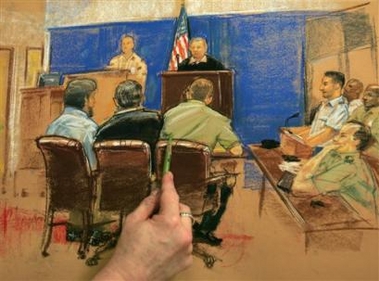

In this photograph of

a drawing by sketch artist Janet Hamlin, reviewed by U.S. military

officials, Hamlin finishes the sketch of Guantanamo detainee Abdul Zahir,

bottom, left, sitting beside his translator, name not permitted, and

lawyer Lt. Col. Thomas Bogar, during a mitlitary tribunal hearing at

Guantanamo Bay U.S. Naval Base, Cuba, Tuesday, April 4, 2006. The

presiding officer Col. Robert Chester, sits at the podium facing Zahir.

Zahir, who is suspected by the U.S. government of being an al-Qaida

terrorist and charged in a March 2002 grenade attack that wounded three

journalists, was presented at a hearing to answer to charges of attacking

civilians, aiding the enemy and conspiracy.

[AP] |

Abdul Zahir did not enter a plea, but his U.S. military defense counsel

almost immediately began asking the judge, Marine Col. Robert S. Chester, what

laws he would follow in presiding over the trial. The Guantanamo Bay trials ¡ª

held inside a cinderblock building perched on a hill on this naval base ¡ª are

the first U.S. military tribunals since the World War II era.

Zahir appeared relaxed during the hearing on charges that include attacking

civilians, aiding the enemy and conspiracy. He stood when the judge entered the

room, unlike some other detainees in pretrial hearings.

Chester refused to be pinned down by the defense on the rules for the trial.

"We will look at military criminal law and federal criminal laws and

procedures," he said.

But, when pressed by the defense attorney, Army Lt. Col. Thomas Bogar, the

judge would not specify which set of laws would guide the trial.

The chief military prosecutor, Air Force Col. Morris Davis, told a news

conference later that the judge can choose from several standards of law "to

provide a full and fair trial."

But the military commission failed to provide a Farsi interpreter for Zahir

and did not provide him with the charge sheet in Farsi, Zahir's native language.

Military Commission officials said they did not know why an interpreter was not

available and that one should have been present for use by the prosecution.

The defense team's interpreter translated the charge sheet and the

prosecutor's remarks.

Chester said the proceedings would resume on July 10 to discuss a trial date.

The defense team said it intended to go to Afghanistan to collect unspecified

evidence.

Critics of the military tribunals say it is a poorly planned ad hoc process.

David Scheffer, a law professor at Northwestern University School of Law in

Chicago, said even the charge of conspiracy, for example, does not exist as a

war crime. Scheffer is a former U.S. Ambassador at Large for War Crimes Issues.

"Technically, the government should have charged participation in a joint

criminal enterprise to commit such crimes, or, if the facts merit, aiding and

abetting," Scheffer told The Associated Press. "But these all generate different

evidentiary requirements than does the crime of conspiracy, which may be why the

government does not want to tackle those tougher standards."

Zahir served as a translator for the Taliban regime in Afghanistan in 1997

and then worked as a translator and money courier for Abdul Hadi al-Iraqi, a

commander and accountant for al-Qaida, the U.S. government said.

Later, Zahir allegedly took a more active role.

- In early 2002, he joined al-Iraqi to plan bomb attacks against U.S. forces

and civilian foreigners in Afghanistan, the military said.

Zahir was captured in July 2002, three months after the attack on the

journalists. In the attack, a grenade was thrown through the window of their

vehicle as they traveled toward Gardez. Toronto Star correspondent Kathleen

Kenna suffered serious leg injuries.

Zahir, an Afghan, also was charged with producing anti-American leaflets to

recruit Afghans living near the U.S. Embassy in Kabul and near the U.S. military

bases in Afghanistan to commit terrorist attacks against American soldiers.

Nearly 500 detainees are held at this U.S. military base in southeastern

Cuba. The U.S. has filed charges against 10 of them.

The Supreme Court is considering a case by another Guantanamo bay detainee

challenging the administration's plans to try him before a military tribunal

that provides fewer legal protections than the civilian court system and was

last used in the World War II era.