Pride of place

Updated: 2014-01-05 08:21

By Xu Junqian(China Daily)

|

|||||||||

Restaurateur Austin Hu locally sources 95 percent of the food he serves out of a dedication to sense of place, educating foreigners and making the world a better place. Xu Junqian reports in Shanghai.

Austin Hu's kitchen is like a little museum of local seasonal specialties from all over China. There's caviar from the sturgeon of Qiandao Lake in Zhejiang province's Hangzhou, wagyu beef from Liaoning province's Dalian and sparkling water from a pristine lake in Heilongjiang province, to name just a few of the items he stocks.

And the 34-year-old American-born-Chinese chef of Madison, a casual fine-dining restaurant in Shanghai, knows each of them and their "growing history" like the back of his hand.

Hu is serving top local produce in a Western establishment in a country where consumers have been scared by unceasing series of food-safety scandals and are willing to pay twice - or even more - the domestic market price for food with foreign labels.

"Up to 95 percent of my food is sourced locally. If we cannot source it locally, we cannot make it," says the chef and owner of one of the city's most popular restaurants. The other 5 percent that "has to be imported" is chocolate, olive oil and dairy products.

After working in some of New York's finest kitchens, such as the Gramercy Tavern, for a decade, the Wisconsin-born Chinese returned to Shanghai, where he spent most of his childhood, in 2010 and started his culinary venture.

But rather than trying to go international or fusion - as most of his peers do - the commitment Hu made with his first venture is to source local produce, although the Chinese names of most of the items were as strange to him as to foreigners.

"What's the difference of cooking here if I source everything from New York, which is not impossible. It should be different. Like food, like wine, there should be a sense of place," Hu says.

"It comes with training. I played with things like molecular cuisine when I was young. But for me, the most natural and right way of cooking is still seasonal and local."

The challenge of having to change the menu every month in accordance with what is available from the market - or, say, nature - is also "exciting" for the adventurous restaurateur.

"It feels very special, like having Christmas every season," Hu says.

After three years of learning and with a special purchasing manager who trots around the country looking for new things, the restaurant now has a food calendar: hairy crab at the beginning of autumn, asparagus when spring arrives, and corn and juicy tomatoes in summer.

"I am a born glutton, and food for me is like a Christmas present (given) by nature," he says.

"Every time the freshest food of the season comes to me, it feels like I am receiving a new toy."

Some of the favorite "toys", or signature dishes, at the restaurant include foie gras and squab meat paired with Chinese hawthorn jam, whose sweet-and-sour flavor perfectly balances the carnivorousness of the other two.

And there is the purely white-looking spaghetti that has calamari and wild rice stems that taste like mushrooms and eggplant, called jiaobai in Chinese. The stems offer an "aha" surprise for domestic diners and "teaches a biological lesson" to foreigners about the endemic plant.

Hu's way of guaranteeing his ingredients' sources are "safe and sound" is simple - perhaps primitive. He and his team of 45 staffers try to meet as many farmers as possible, talk to people "who feel the same way I feel about food" and taste everything that comes into his kitchen.

"Faith (is) the staple" of his kitchen, he says. "This is a problem every single country has in the world," he explains.

"Actually, every industry in the world has its own problem, no matter what. But the answer that 'we are going to completely throw away Chinese ingredients and use imported ones only' is a very nearsighted and short-term one.

"As a food provider, part of our responsibility is to the food system, and we should try to change the food system somehow. It takes time. China has made incredible progress, but it has growing pains."

Cooking locally comes with a price - a much higher one than expected - since people generally believe grown-in-China products should be cheaper than imports.

The clientele of the restaurant with an average cost per head of about 200 to 300 yuan ($33-50) is half local and half foreign. Hu admits that at first some of the diners would sniff and leave the restaurant after learning they were paying "that much for local products".

But Hu has set his mind on proving them wrong. And the result is rewarding. Business has been growing annually, despite frustrating moments and misunderstandings from guests who think he uses local produce to lower the cost.

"I am huaqiao (overseas Chinese) and Chinese by descent. These are my people. I am here because I believe in the potential of what China can be in 20 years' time. If I can be a small part of what that future can be - somehow a footnote of that history - I think I have done my job," Hu says.

"Our day-to-day business is making food for people and making a living ourselves. But on a long time scale, we are looking for what we can contribute to make the world a better place."

Contact the writer at xujunqian@chinadaily.com.cn.

|

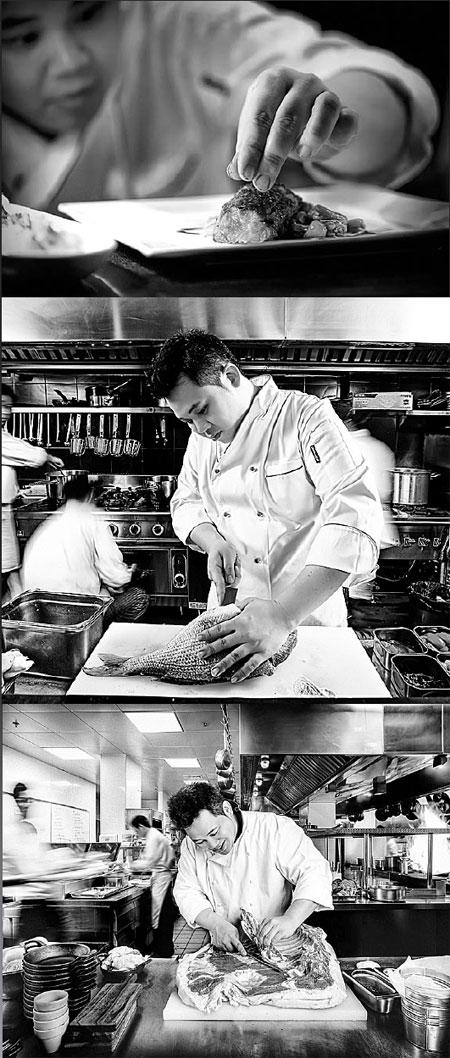

After working in some of New York's finest kitchens, Austin Hu returns to Shanghai. Rather than trying to go international or fusion, the commitment Hu has made is to source local produce and cook locally. Photos Provided to China Daily |

(China Daily 01/05/2014 page5)