A glider built to study the ozone

Updated: 2013-11-03 08:11

By Matthew L. Wald(The New York Times)

|

|||||||||

Bend, Oregon

It might be the weirdest part of the atmosphere, 24 kilometers above the polar regions, where vast stratospheric clouds of nitric acid and water vapor shimmer in iridescent pink while human-made chemicals play havoc with the ozone layer.

Scientists long to study the stratosphere at close range. But this is almost the edge of space, far too high for a conventional airplane in level flight.

How to get there? In a glider.

Without the weight of engines or fuel, a glider can be lifted by natural atmospheric phenomena, engineers say. So a team of scientists, aviation buffs and entrepreneurs is building a two-seat sailplane designed to withstand the peculiar hazards of stratospheric flight. The journey is scheduled for August 2015.

The glider will be shipped by freighter to El Calafate, Argentina, where winds from the Pacific Ocean are deflected by the Andes Mountains to create a standing wave, with updrafts of nine meters per second.

"These mountain waves get so steep and energetic, they turn into white water," said Edward J. Warnock, head of the Perlan Project, the nonprofit that is building the glider, Perlan II.

A single-engine plane will tow the glider to meet these waves, at about 3,000 meters. Where the waves weaken, at about 18,000 meters, the glider is supposed to intercept another phenomenon, the polar vortex - circulating winds that act like a giant cyclone during the austral winter, delivering a strong uplift. If it can catch that current, the glider will soar still higher, into the Perlan Clouds, and higher, into the ozone hole, where the chemical reactions that disrupt the ozone layer take place. (Perlan is the Icelandic word for "pearl," describing the clouds' sunlit glow.)

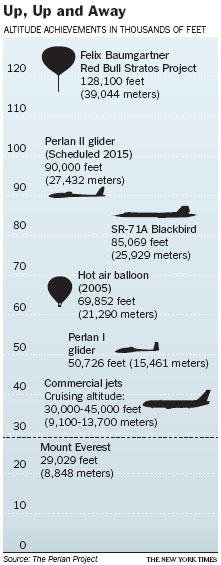

The aim is to go to 27,432 meters and set a new altitude record for a glider. The plane's predecessor, Perlan I, set the record of 15,461 meters on August 30, 2006.

Perlan II will cost an estimated $7.5 million. The

organizers include Dennis Tito, the pension fund manager who paid $20 million to visit the International Space Station, and, until he was killed in the 2007 crash of his single-engine plane, Steve Fossett, the aeronaut who flew Perlan I.

The new sailplane will have a wingspan of 25 meters and weigh just 770 kilograms counting crew. The builders say Perlan II is 80 percent complete. Huge carbon-fiber pieces that look like a woven fabric fill most of a hangar.

In the end, all will be painted a reflective white to stop the sun from heating the parts enough to weaken the epoxy. (Inside the cabin, though, the air will be near freezing.)

Long wings with a short distance from leading edge to trailing edge have low drag, essential in a plane with no engines. But as the wings get longer, the bending forces become greater, so the wings require a stiffer internal spar, which adds thickness.

"You're always working trade-offs," said Einar K. Enevoldson, the founder and chief pilot of the project, who was Mr. Fossett's co-pilot on the Perlan I flight.

Mr. Enevoldson, 81, has extensive experience in fighters and research planes. His reflexes are not the same, he said, but his judgment in the tricky business of finding the uplifts is still good.

The glider's system will be tricked by the thin atmosphere into showing an airspeed of 74 kilometers an hour, about what it needs to stay aloft. But for the speed indicator to get to that reading in such low-density air, the actual speed will have to be about 540 kilometers per hour.

And this, indirectly, sets the altitude limit. The challenge for the glider is to move fast enough to get sufficient lift in the thin air to stay airborne, without approaching the speed of sound, which causes unacceptable stresses on the airframe.

And the high altitude will introduce other complications.

One is the need to pressurize the cabin so human lungs can overcome low air pressure - something other airplanes do with an engine.

The solution is to seal the tiny cabin as the plane ascends, and bleed off a little air through a valve so the cabin pressure mimics what it would be at 4,400 meters. The sealed cabin needs spaceship-style scrubbers to remove the carbon dioxide and the moisture that would otherwise produce ice on the windows and walls. There is no way to warm the plane so the two pilots will wear socks with heaters in their soles, Mr. Enevoldson said. Squeezed into a fuselage about 90 centimeters in diameter, they will bring sandwiches and wear diapers.

The stratosphere is ripe for close study, scientists say. It is where the sun continuously breaks apart molecules of ozone.

The space shuttle used to traverse it at several times the speed of sound. Spy planes have reached that altitude, but only for brief periods. Perlan will cruise for hours at a time.

James G. Anderson of Harvard University, who is not affiliated with the project, said, "The idea of extended observations from a platform in the 70-to-90,000 foot range has huge potential scientific advantages."

The New York Times

|

A model of the glider that will soar to 27,432 meters. Einar K. Enevoldson, right, is the chief pilot of the project and Morgan Sandercock is project manager. The flight is set for August 2015. Leah Nash for The New York Times |

(China Daily 11/03/2013 page9)