World of the ancients

Updated: 2013-10-13 08:24

By John Noble Wilford(The New York Times)

|

|||||||

Greco-Roman ideas passed on to future mapmakers John Noble Wilford

Long before people could look upon Earth from space, completing a full orbit every 90 minutes, the Greeks and the Romans of antiquity had to struggle to understand their world's size and shape. Their approaches differed: the philosophical Greeks, it has been said, measured the world by the stars; the practical, road-building Romans by milestones.

As the Greek geographer Strabo wrote at the time: "We may learn from both the evidence of our senses and from experiences, that the inhabited world is an island, for wherever it has been possible for men to reach the limits of the earth, sea has been found, and this sea we call 'Oceanus.' And whenever we have not been able to learn by the evidence of sense, there reason points the way."

Strabo's words will greet visitors to a new exhibition, "Measuring and Mapping Space: Geographic Knowledge in Greco-Roman Antiquity," at the Institute for the Study of the Ancient World in Manhattan through January 5. The show brings together more than 40 objects in an overview of Greco-Roman geographical thinking - art and pottery, as well as maps based on classical texts.

Hardly any original maps survive; the ones in the exhibition were created in the Middle Ages and the Renaissance from Greek and Roman descriptions.

"Geography is not just maps," said the guest curator, Roberta Casagrande-Kim, a scholar of classical concepts of the underworld that go back well before Dante took his journey through the nine circles of hell. "There is also the cognitive side underlying mapping," she said.

Plato wrote of Socrates saying the world is large and those who dwell between Gibraltar and the Caucasus - in his imagery - live "in a small part of it about the sea, like ants or frogs about a pond, and that many other people live in many other such regions."

An early advance in Greek thinking was Aristotle's discovery, in the latter half of the fourth century B.C., that the world must be spherical. He based this on observations of lunar eclipses, ships disappearing hull first on the horizon, and the changing field of stars observed as one travels north and south.

Then Eratosthenes, a librarian at Alexandria in the third century B.C., employed the new geometry to measure the world's size with simultaneous angles of the sun's shadow taken at widely distant sites in Egypt. That yielded a remarkably accurate measure of Earth's circumference: it was clear that the world they knew - the three connected continents of Asia, Europe and Africa - was only a part of lands unknown.

Both the Greeks and the Romans identified the frigid Arctic Circle, the northern temperate hemisphere, the torrid Tropic of Cancer, the southern temperate zone and the South Pole.

Across the wall of the first gallery is projected a digital replica of the Peutinger Map, about seven meters long and more than half a meter high, illustrating how Roman mapping was at once practical and magnificent. It charts the empire's roads, cities, ports and forts from Britain to India. Sketches of trees mark forests in Germany. Topography is minimal, roads are off-scale wide, towns are indicated by symbolic walls or towers.

An early copy of the map came to light in the 17th century and was owned for years by Konrad Peutinger, a Hapsburg diplomat and map collector. It is now in the Austrian National Library in Vienna. Richard J. A. Talbert, a historian at the University of North Carolina, has concluded that the map, probably created in the early fourth century A.D., may have been intended to impress the emperor's subjects and guests.

The most influential of the ancient Greeks was Claudium Ptolemy, the foremost scholar at the Alexandria library in the second century A.D. Two of his books, one on astronomy, and another on geography, were finally translated into Latin in the Middle Ages.

Notes accompanying the exhibition point out that Ptolemy's "Geographia" provided ample information on locations of ancient lands and cities, enabling Renaissance cartographers to prepare the first fairly modern world maps, the "Mappa mundi" style that was followed for the next couple of centuries.

Even Ptolemy's errors were influential. Instead of using Eratosthenes' more accurate estimate of Earth's size, Ptolemy handed down a serious underestimate that later apparently emboldened Columbus to think he could sail west to reach China or Japan.

Instead, he reached landfall in what became known as the West Indies - about the distance from Europe that Ptolemy had led him to expect, but with no "Grand Khan" in sight.

So it was perhaps no coincidence that the rediscovery of Greco-Roman geography fostered the age of Western exploration. After 1492, there were new worlds to measure and map. Within two centuries, exhibition notes remind us, "the primacy of ancient geographic knowledge and mapping conventions came to an end."

New discoveries and technologies had made Greco-Roman geography obsolete. But its influence helped shape the way we still look at the world.

The New York Times

|

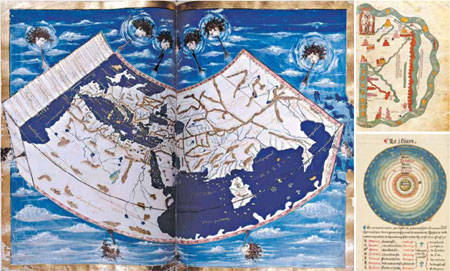

On view: clockwise from above, a map from a copy of Ptolemy's "Geographia"; a copy of an eighth-century "Commentary on the Apocalypse and the Book of Daniel"; a diagram of the solar system from a 16th-century French text; below, a third-century coin that shows a globe. New york public library; top right, the morgan library and museum; bottom right, houghton library, harvard university; below, american numismatic society |

(China Daily 10/13/2013 page9)