In pursuit of literary revival

Updated: 2013-09-29 07:25

By Isma'il Kushkush(The New York Times)

|

|||||||

KHARTOUM, Sudan - On the corner of an old colonial building in downtown Khartoum sits the city's oldest bookstore, Sudan Bookshop. It was established in 1902, three years after Britain established control over Sudan, and for a long time it was a magnet for the city's civil servants, politicians and intellectuals.

Today, it is dusty, cold and empty of buyers. It displays books published in the '70s and '80s.

"We used to order a shipping container of books every month or two," said El Tayeb Abdel-Rahman, 69, the shop's manager. "But now no one reads anymore."

As people do elsewhere, the Sudanese lament that technology and the Internet have been turning eyes away from pages and toward screens. But there is more at work here, in a city long famous as a big market for Arabic writers. Books and reading are embedded profoundly in Khartoum's self-image and the country's history, and there is growing worry that the collapse of the book culture mirrors the country's overall decline.

|

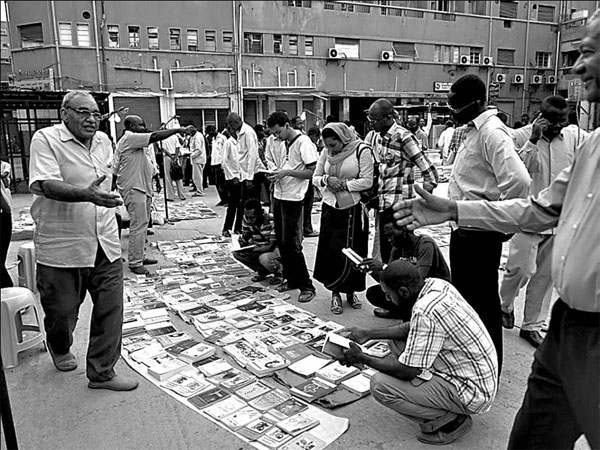

A new wave of activism in Sudan is rekindling an interest in reading and books. Used-book sellers in Khartoum. Isma'il Kushkush / The New York Times |

Most Sudanese are more concerned with bread than books. Years of war, drought and economic privation have left deep marks. A once prestigious education system has crumbled, and the number of bookstores in Khartoum has declined.

But a new wave of activism is driving efforts to revive Khartoum's reputation as a literary city. "We want to bring people back to books," said Abdullah Al-Zain, 58, who started a project with friends called Mafroush - a Sudanese Arabic word meaning displayed.

Once a month, used-book sellers come to Khartoum's Etinay Square and lay their books on the ground over cloth sheets or flattened carbon boxes. Hundreds of book lovers, including students, artists and writers, showed up recently, some gazing over the sprawl of covers, some flipping pages attentively. Others arrived with more books for the display.

Al-Mutasim Hassan, 25, a graduate student, came searching for philosophy books. "I think Mafroush is a creative endeavor, and you meet other readers," he said.

Mr. Hassan holds himself apart from those who think "Facebook and chat are the only expressions of progress," he said.

"I find myself, however, that when I read a book, I feel alive."

For many who are trying to revive reading here, the Internet is turning into an ally. "The Internet is not necessarily an enemy of books," Mr. Al-Zain said. "It is so only for those who want it to be such. We use the Internet to promote our programs."

Across town, in Khartoum's Green Square, another group is also trying to encourage Sudanese to return to books. Hundreds of Sudanese youths met in the square one afternoon, each with a book in hand. For the next few hours, they sat on the grass and read books or joined a discussion circle.

"We want to revive the habit of reading in public spaces," said Raghda El-Fatih, 18, a volunteer with Education Without Borders, a group that called for a "Khartoum Is Reading" day. Education Without Bordersgrew out of a discussion between two college graduates who wanted to tackle the many problems facing education in Sudan. Their Facebook page now has thousands of members.

"One member suggested organizing a day for reading," said Wisal Hassan, 25, one of the group's founders. So far, the group has organized two reading days, including one that coincided with the United Nations' World Book Day.

"It's been a great success," Mr. Hassan said.

A sense of Sudanese tradition infuses the revival efforts, and those of writers trying to fuel them. In the 1930s, Khartoum was having a cultural renaissance that included the publication of the first Sudanese magazine, Al-Fajr, said one writer, Kamal El Gizouli. The generation that followed inherited the love of reading, and built on it. "The '60s was a period of optimism, ideological debates, and people were self-motivated," Mr. El Gizouli said.

That period created a pantheon of writers revered in Khartoum, where Arabic authors like the native Sudanese Tayeb Salih, the Egyptian Abbas El-Aqqad and the Syrian Nizar Qabbani became vital inclusions on readers' lists that also included writers like Chinua Achebe, George Bernard Shaw and Ernest Hemingway.

Khartoum had nearly 400 bookstores, publishers say, including the five-story Al-Dar Al-Sudaniya for Books that claimed to be the largest bookstore in the Arab world. It survives, but others are struggling.

At Sudan Bookshop, Mr. Abdel-Rahman said he had maintained his pride despite tough times.

"I am working with a loss," he said. "But it would be shameful to close down such an institution."

The New York Times

(China Daily 09/29/2013 page9)