Orcas' captivity inspires ethics debate

Updated: 2013-08-11 08:07

By James Gorman(The New York Times)

|

|||||||

|

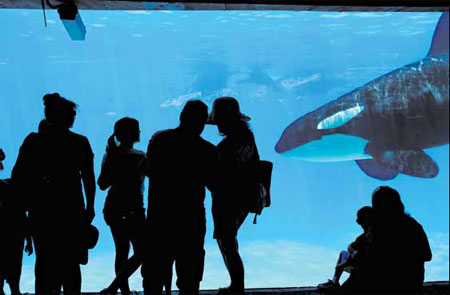

An estimated 45 orcas are kept in captivity worldwide at marine parks, half of them by SeaWorld in the United States. Sandy Huffaker for The New York Times |

Should the killer whale, or orca, one of the most social, intelligent and charismatic animals on the planet, be kept in captivity by human beings?

That is a question asked more frequently than ever by scientists and animal welfare advocates.

Killer whales, found in all of the world's oceans, were once as despised as wolves. The name apparently came not because it was a vicious whale, but because it preyed on whales, along with fish, penguins and seals.

With life spans that approach those of humans, orcas have strong family bonds, elaborate vocal communication and cooperative hunting strategies. And their beauty and power, combined with a willingness to work with humans, have made them legendary performers at marine parks worldwide since the 1960s.

Some scientists and activists have argued for years against keeping them in artificial enclosures and training them for exhibition. They have asked for more natural settings, like enclosed sea pens, as well as an end to captive breeding. (Orcas are no longer taken from the wild.)

Now the issue has been raised with new intensity in the documentary film "Blackfish," which is playing in the United States and in Britain, Canada and New Zealand; and in the book "Death at SeaWorld," by David Kirby, just released in paperback.

The film and book focus on the 2010 death of Dawn Brancheau, a trainer, at SeaWorld in Orlando, Florida. She was dragged underwater by a whale called Tilikum, which had been involved in two earlier deaths.

Both the book and film argue that Tilikum's actions were deliberate and that his behavior was a result of the psychological damage of captivity. SeaWorld has said the death was an accident.

Beyond the death lies a fundamental disagreement about whether killer whales, and other cetaceans - whales, dolphins and porpoises - should be held captive at all. It is reminiscent of the movement to put all captive chimpanzees into sanctuaries.

But the situation for killer whales is different. There are many fewer in captivity - a total of 45 worldwide, according to the organization Whale and Dolphin Conservation - and thousands of people have come to love them partly because of the very exhibitions in marine parks that disturb opponents of captivity.

But even some scientists who have worked with captive dolphins set orcas apart because of their size, their range of movement in the wild and the close-knit nature of their social groups.

The males can reach 10 meters in length and weigh up to 1,000 kilograms. The females are smaller, but live longer. Males can reach 60 years; females 90 years. The whales live in family groups, or pods. Subgroups differ in diets and physical traits. Orcas can travel up to 160 kilometers in a day. The behaviors of different groups are so diverse that scientists talk about them as having different cultures.

Opponents of captivity recognize that the animals, for their own safety, should not be released into the wild. Rather they would like to see the orcas kept in larger, more natural settings.

Naomi Rose, a whale biologist, said creating sanctuaries for orcas is "highly feasible," and should be done by companies like SeaWorld, which has 22 orcas.

Some Sea Life aquariums, mostly in Europe, have been exploring the possibility of a sanctuary, such as a cove or a bay, for bottlenose dolphins with Whale and Dolphin Conservation.

But both SeaWorld and the Association of Zoos and Aquariums say that such sanctuaries would be a solution for a problem that does not exist.

Christopher Dold, vice president of veterinary services at SeaWorld, argues that orcas at SeaWorld facilities already have "a phenomenal quality of life." SeaWorld says it offers a high level of veterinary care and psychological enrichment programs.

At a meeting in New Zealand of the Society for Marine Mammalogy, Dr. Rose will be one of several co-authors presenting a paper about survival of captive orcas. She said it shows that captive orcas do not do as well as wild ones. The scientific community, she said, needs to confront some "hard truths."

The New York Times

(China Daily 08/11/2013 page11)