In Brazil, growing prices enrage the middle class

Updated: 2013-08-04 07:18

By Simon Romero(The New York Times)

|

|||||||

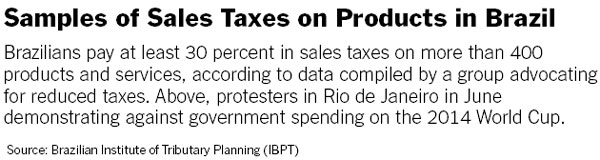

SAO PAULO, Brazil - For Brazilians seething over wasteful spending by the country's elite, the high prices they must pay for just about everything - a large cheese pizza can cost almost $30 - only fuel their ire.

"People get angry because we know there are ways to get things cheaper; we see it elsewhere, so we know there must be something wrong here," said Luana Medeiros, 28, who works in the Education Ministry.

Brazil's protests grew out of a campaign against bus fare increases. Residents of Sao Paulo and Rio de Janeiro spend much more of their salaries to ride the bus than residents of New York or Paris. But economists note that the fares are just one of the struggles Brazilians face.

Inflation is about 6.4 percent, with many in the middle class complaining that they are bearing the brunt of price increases. Limiting the authorities' maneuvering room, the popular indignation is festering at a time when huge stimulus projects are failing to lift the economy, raising the specter of stagflation in Latin America's largest economy.

"Brazil is on the verge of recession now that the commodities boom is over," said Luciano Sobral, an economist. "This is making it impossible to ignore the high prices which plague Brazilians."

Brazil's sky-high costs can be attributed to an array of factors, including transportation bottlenecks that make it expensive to get products to consumers, protectionist policies that shield Brazilian manufacturers from competition and a legacy of consumers somewhat inured to relatively high inflation, which remains far below the 2,477 percent reached in 1993.

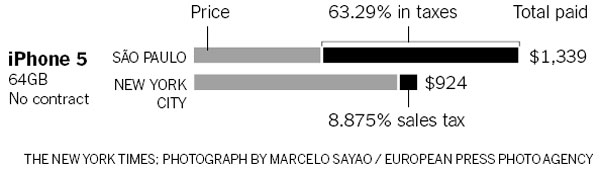

But economists say much of the blame for the high prices can be placed on a dysfunctional tax system that prioritizes consumption taxes, which are relatively easy to collect, over income taxes.

Alexandre Versignassi, a writer who specializes in deciphering Brazil's tax code, said companies were grappling with 88 federal, state and municipal taxes, a number of which are charged directly to consumers. The authorities issue an estimated 46 new tax rules every day, he said.

Making matters worse for many Brazilians, loopholes enable the rich to avoid taxation on much of their income.

The result is that many products made in Brazil, like automobiles, cost much more here than in the countries that import them. One example is the Gol, a subcompact car produced by Volkswagen in the Sao Paulo metropolitan area. A Gol sells for about $16,100. In Mexico, the equivalent model, made in Brazil but sold to Mexicans, costs thousands of dollars less.

The ability of many Brazilians to afford such cars reflects positive economic changes over the past decade, like the rise of millions of people from grinding poverty and a decline in unemployment, which is now at historically low levels. Salaries climbed during that time, with per-capita income now about $11,630, as measured by the World Bank, compared with $6,990 in neighboring Colombia and $50,970 in Canada.

A resident of Sao Paulo, Brazil's financial capital, has to work an average of 106 hours to buy an iPhone, while someone in Brussels labors 54 hours to buy it, said the investment bank UBS.

Stroll into any international airport in Brazil, and such imbalances are vividly on display, with residents flying off to countries where goods are much cheaper.

Seeking to prevent such shopping binges from getting out of control, the federal police screen travelers upon arrival, picking out people whose luggage appears to bulge with too many items. If it can be proved that Brazilians spent over a certain limit abroad, they are immediately forced to pay taxes on their purchases.

Such screening catches foreigners, too. In May, the police at Sao Paulo's international airport arrested two American Airlines flight attendants, both American citizens, on smuggling charges after they were found going through customs carrying a total of 14 smartphones, 4 tablet computers, 3 luxury watches and several video games. The smartphones were hidden in their underwear, the police said, and were intended to be sold on the black market.

Before the protests began, Brazil's government had begun trying to combat price increases. The central bank raised interest rates after an uproar over food prices this year contributed to inflation fears. The authorities removed some taxes on some products, like cars. Even so, inflation remains high while the economy remains sluggish, leaving many Brazilians fuming about the high taxes embedded in the price of products they buy.

A new federal law requiring retailers to detail on receipts how much tax customers are being charged has fed some of this anger. Fernando Bergamini, 38, a graphic designer, was stunned after spending $92 one recent day on groceries like tomatoes, beans and bananas, only to glance at his receipt and discover that $25 of that was in taxes.

Mr. Bergamini said: "It is shocking given the services we receive for giving the government our money. Seeing it like this on a piece of paper makes me feel indignant."

The New York Times

(China Daily 08/04/2013 page10)