Outsider gets his due, but he's still restless

Updated: 2013-07-21 08:26

By Ben Sisario(The New York Times)

|

|||||||

|

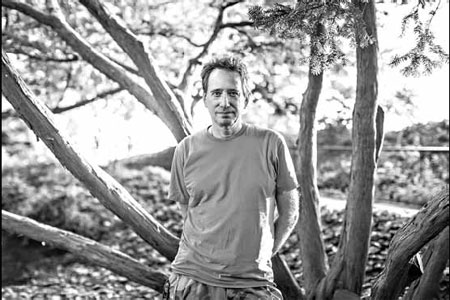

"People are not going to understand what I'm doing until I'm dead." John Zorn, Composer and saxophonist. Chad Batka for The New York Times |

The composer and saxophonist John Zorn, for decades one of the most prolific and polarizing figures in New York's downtown music scene, sat silently in the Guggenheim Museum atrium in June waiting for the start of a show in Zorn@60, a worldwide festival marking his 60th birthday.

The festival, which continues through September at temples of high culture like the Metropolitan Museum of Art, celebrates Mr. Zorn as a major American composer whose work crosses just about every stylistic boundary imaginable: jazz, classical, klezmer; from caustically noisy to sweetly lyrical.

But if anything can define Mr. Zorn and his work, it is his stance as a defiant outsider - even upon a moment of insider acceptance.

He has built an influential career on his own terms, and has released more than 30 albums of original work on his own label in the past three years.

"What happens when you get to the age of 60," he said, "is that you have no more doubts. I know why I'm here on this planet. I know what I need to do."

The Guggenheim concert featured two sinuously beautiful works for female vocals, with mystical texts and echoes of 14th-century polyphony - a long way from the manic hybrids of jazz, thrash and B-movie soundtracks that brought Mr. Zorn to fame in the 1980s, on albums like "The Big Gundown" and "Spillane," and with his band Naked City.

George E. Lewis, a professor of music at Columbia University in New York and a trombonist who has played with him, said that this "extreme openness to new ideas" linked Mr. Zorn to both the jazz avant-garde and to the composer John Cage. "The early jazz musicians would always tell you that you should listen to everything," Mr. Lewis said. "John took that about as literally as can be."

Yet that openness means that Mr. Zorn has remained on the margins of several musical worlds, with jazz critics particularly scandalized by albums like "Spy vs. Spy" (1990), which featured Ornette Coleman pieces played with the frantic intensity of hardcore punk.

To maintain his output, Mr. Zorn has adopted a strict discipline. He lives alone in the same apartment where he has lived since 1977 and works constantly, eliminating distractions like magazines, television or people.

"People are not going to understand what I'm doing until I'm dead," he said. "Ultimately people in the academy and people on your side of the fence are most happy when their subjects are dead, because they're not going to turn around and do something that proves that you were wrong."

Mr. Zorn returned to the subject of collaboration, which, for him, is essential to composition itself.

"The job of a composer is putting something down on a piece of paper that will inspire the person who's playing," he said.

To publicize his and others' music, he has his own label, Tzadik, which has released more than 600 albums since 1995 (about 150 of them featuring his music). In 2005 he founded the Stone, a club in the East Village where musicians share the booking duties and keep 100 percent of the door receipts.

Mr. Zorn said that a "messianic" zeal to stand out marked his early days. That urge has waned, and Masada, a music project he began in the early 1990s, was a bridge.

Masada explored his roots and expanded the idea of Jewish music through a "songbook" that linked klezmer and jazz.

He wrote the first tunes under strict guidelines: Every melody must fit on one music staff, every tune on one page. But when he revisited Masada a decade later he had found "the courage to write a pretty melody," and more than 300 songs came out in a few months. "I used to look at composing music as problem solving," he said. "But as I get older, it's not about problem solving anymore. There are no solutions, because there are no problems. You just turn the tap and it flows out."

The world has also caught up. The past decade's shuffle-mode aesthetics echo Mr. Zorn's 1980s eclecticism, and his self-determinism has become the norm.

Asked whether there could ever be another like him, Mr. Zorn said: "I feel like there will be many more. This is a new way of making music - not just focusing on being a specialist, but having friends and connections all over the place. People are coming out of conservatories wanting to improvise. They want to play in a club. They want to make some horrible noise."

The New York Times

(China Daily 07/21/2013 page12)