Imbibe, then test, with care

Updated: 2013-07-21 08:25

By Matthew L. Wald(The New York Times)

|

|||||||

Cheap microelectronics are democratizing the world of blood alcohol measuring equipment. A field once dominated by $10,000 machines owned only by police departments is now filled with devices that cost as little as $30 and can hang from a key chain.

A recent proposal by the United States National Transportation Safety Board to drop the legal definition of drunk to 0.05 percent blood alcohol from 0.08 percent has kindled interest in the personal units, some of which are sold as smartphone accessories.

Safety experts warn that a reassuring reading on one of these devices does not guarantee someone is safe to drive. And manufacturers, wary of liability, don't endorse the idea, either.

These machines do offer some form of measurement beyond counting drinks, though.

Keith Nothacker, whose company, BACtrack, sells a so-called fuel cell unit that displays its results on an iPhone via a Bluetooth link, argues that "law-abiding citizens can't possibly be expected to know the difference" between 0.05 blood alcohol content and 0.08 blood alcohol content without doing a test. BACtrack displays a graph that predicts future blood alcohol levels, all the way down to zero. The device sells for $150.

Inside the hand-held, battery-powered unit is a metallic catalyst that starts a chemical reaction, which the unit uses to calculate blood alcohol.

Mr. Nothacker's company describes its product as "pocket-sized peace of mind," but he insisted that its purpose was not to assure a drinker that he or she would be under the limit if pulled over by the police. He said it was simply an "an educational tool."

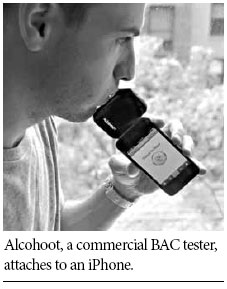

A competitor, Alcohoot, is promising shipment in September of a similar $75 model that plugs into an iPhone. Alcohoot's product includes an app that displays a list of local restaurants where people can eat and sober up and a list of taxi companies.

Another type of device, which typically costs $30 to $70 and is made by manufacturers including BACtrack, relies on a tin oxide semiconductor. Applying alcohol to the sensor changes its ability to conduct electricity, giving an easy indication of blood alcohol. But the sensor may go bad after three to six months, and can also be prone to giving false positives, mistaking acetone, hair spray or other common contaminants for alcohol.

The machines are all calibrated by the manufacturer using a device approved by the United States Transportation Department that takes in a solution with a known alcohol concentration and puffs it out in a way similar to human breath.

BACtrack recommends annual recalibration of its costlier models, which it will do for $19.95.

Most of the cheap semiconductor models are probably bought for personal use, manufacturers say. The fuel cell units are sold to drinkers for their own use as well as to employers and parents.

The testing equipment used by police, on the other hand, is usually not sold to private citizens. A driver pulled over by the police and subjected to a blood alcohol test back at the police station will most likely blow into a device about the size of a desktop printer. Most police departments use a model called the Intoxilyzer. It sells for about $10,000 and its results are widely accepted in court.

Police officers will often stick a flashlight-shaped device through the driver's window before taking the person to the station for testing. The light given off by this $600 mobile detector mostly serves to disguise its true purpose: an air sensor that sniffs for alcohol.

J.T. Griffin, a lobbyist at the Washington office of Mothers Against Drunk Driving, warned that the consumer models were sometimes used by people who wanted to come as close to the limit as legally possible. And, he said, "If the device isn't calibrated properly, it could give them the wrong reading and they might drive anyway."

The New York Times

(China Daily 07/21/2013 page10)