Museums fight for Nazi-looted art

Updated: 2013-07-14 08:06

By Patricia Cohen(The New York Times)

|

|||||||

|

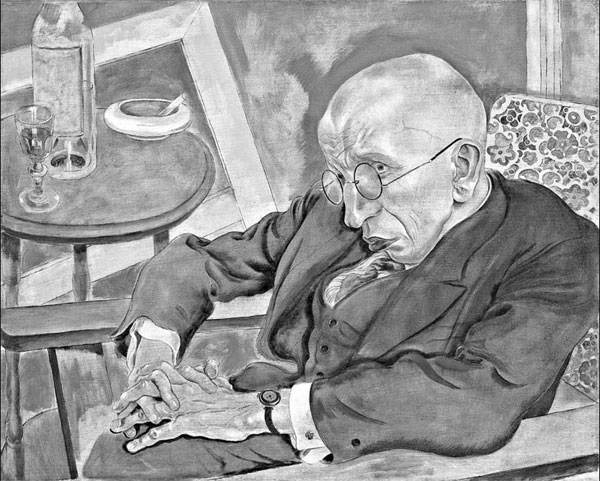

The heirs of George Grosz want the Museum of Modern Art to return the artist's works including his 1927 portrait, "The Poet Max Herrmann-Neisse," and, below, "Self-Portrait With Model" (1928). Estate of George Grosz / Licensed by Vaga, New York; museum of modern art |

Not until 1998, when 44 nations including the United States signed the groundbreaking Washington Principles on Nazi-Confiscated Art, did governments and museums formally embrace the idea that they have a special responsibility to repair the damage caused by the wholesale looting of art owned by Jews during the Third Reich.

Now, 15 years later, historians, legal experts and Jewish groups say that some American museums have backtracked on their pledge to settle Holocaust recovery claims on the merits, and have resorted instead to tactics to block survivors or their heirs from pursuing claims.

In some cases, museums like the Detroit Institute of Arts, the Toledo Museum of Art in Ohio, the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston and the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York have tried to deter claimants from filing suit by beating them to the courthouse and asking judges to declare the museums the rightful owners.

"The response of museums has really been lamentable," said Jonathan Petropoulos, the former research director for art and cultural property for the Presidential Advisory Commission on Holocaust Assets, who has been hired by claimants to do research. "It is now so daunting for an heir to go forward."

At stake are the fate of valuable works of art, the reputations of elite cultural institutions and the legal issue of whether the American judicial system is capable of addressing restitution claims.

Both the Association of Art Museum Directors and the American Alliance of Museums insist that their members follow guidelines requiring them to respond "quickly and scrupulously" to restitution requests. Christine Anagnos, executive director of the museum directors association, said most cases are resolved through negotiation.

|

All rights reserved, Estate of George Grosz / Licensed by Vaga, New York; image courtesy of museum of modern art |

Museum officials say they turn to procedural tactics like invoking deadlines only after concluding that a claim is unfounded.

But Stuart E. Eizenstat, a former special State Department envoy who negotiated the Washington Principles, said museums have adopted a harder line, partly in response to court victories by art institutions and waning pressure from the government.

"The essence of the Washington Principles comes down to one sentence," he said. "Let decisions be made on the merits of the case rather than technical defenses."

No one disputes that, even with databases that list looted art, it takes considerable effort to track artworks from Nazi-occupied countries, which typically have gaping holes in their provenance. There is also agreement that not all claims are valid.

Critics, including the Holocaust Art Restitution Project and the Commission for Art Recovery, say problems arise in cases where documentation is missing or it is unclear whether Jewish owners freely parted with a work of art or were coerced by the Nazi authorities into selling it for a pittance.

Mr. Eizenstat is among those who have long argued that the courts are inherently ill suited to resolving restitution cases and that to avoid litigation the United States should create an independent mediation board, as several European countries have.

Raymond Dowd, a partner at the Manhattan firm Dunnington, Bartholow & Miller who often handles restitution claims, complains that museums often review the evidence and decide on their own if a case is valid. Museums often fail to make their original research on a work's provenance or sale available or to submit the scholarship to peer review, he added.

The family of the artist George Grosz has long fought to recover three works from the Museum of Modern Art, arguing they were the subject of a forced sale after Grosz fled the Nazis in 1933.

A federal judge dismissed the Groszes' lawsuit in 2011, citing the statute of limitations. Research commissioned by the museum had concluded that Grosz's Jewish dealer, Alfred Flechtheim, had fair title and freely sold the works. The Groszes' experts declared that Flechtheim was forced to flee Germany after his gallery was given to a Nazi Party member.

That interpretation was affirmed in April by the German advisory commission in an unrelated case. While there is "an absence of concrete evidence," the commission concluded, "it is to be assumed that Alfred Flechtheim was forced to sell the disputed painting because he was persecuted."

Margaret Doyle, a spokeswoman for MoMA, said the museum has no interest in retaining works to which it does not have clear title. "After years of extensive research," she said, "including numerous conversations with Grosz's estate, it was evident that we did in fact have good title to the works by Grosz in our collection and therefore an obligation to the public to defend our ownership appropriately."

George Grosz's son Martin, 83, points to a letter his father wrote in 1953 after seeing one of the works, "The Poet Max Herrmann-Neisse," at MoMA: "Modern Museum exhibits a painting stolen from me (I am powerless against that) they bought it from someone, who stole it."

"He was very reluctant to in any way assail or complain about the treatment he got from anybody in the United States," Mr. Grosz said, explaining why his father never fought to recover the work.

When refugees complained, Mr. Grosz said, his father would respond: "You should kiss the ground you're walking on because they let you in."

The New York Times

(China Daily 07/14/2013 page12)