'Jungle Book' poses concerns

Updated: 2013-06-30 07:37

By Rob Weinert-Kendt(The New York Times)

|

|||||||

|

Mary Zimmerman has infused her stage version of "The Jungle Book" with Indian influences. A rehearsal. Photographs by Liz Lauren |

|

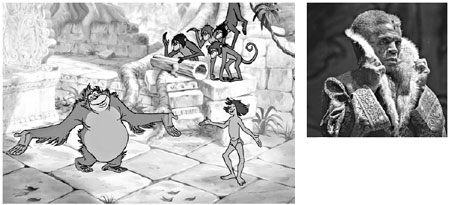

Many think the Disney film's jazz-singing orangutan has racial overtones. Andre De Shields believes his King Louie will transcend the role's racial questions. Disney |

CHICAGO - As the music director for a stage production of "The Jungle Book" was leading an 11-piece band through a show tune, there were musicians seated around him on sitar, vina, tabla and Carnatic violin. To his left, a jazz sextet sat on chairs with music stands. These players rolled through the Dixieland rumble of the show's "I Wanna Be Like You" and the sunny swing of "The Bare Necessities," as sax and sitar traded improvised solos, and tabla and drums found fresh grooves together.

This jam session between Indian and jazz musicians performing old Disney tunes was a rehearsal for the stage version of "The Jungle Book," being produced by Mary Zimmerman at Chicago's Goodman Theater in conjunction with the Huntington Theater Company in Boston. Richard M. Sherman, a songwriter on the 1967 animated film, looked on as they played, tinkering with lyrics, chiming in with musical advice, or singing along.

This isn't the first time that Disney has entrusted a beloved animated musical to a visionary director whose big idea is to take aesthetic inspiration from the story's far-flung location, in this case India. That could also describe the winning gamble Disney took in 1997 with Julie Taymor and the African elements she added to her stage version of "The Lion King."

But Disney is not producing this "Jungle Book," though it has provided financial support and given Ms. Zimmerman full access to the film's script and score, including several songs that weren't in the movie. Whether the show will have a life that includes Broadway depends on whether audiences accept the stylized world she is creating.

If expectations have been ratcheted down, it's partly because Disney doesn't see "Jungle Book" as its most stage-ready property. But it's also because Ms. Zimmerman's unique process of adaptation - she starts without a script, then works on writing one up until opening night - requires autonomy Disney could only agree to if it weren't producing.

The show, which officially opens on July 1, has already been extended through August 11. But the work has hardly been seamless. Ms. Zimmerman has infused Indian influences into the show, taking her cue from the setting of the Rudyard Kipling stories that were the basis of the film. Yet in a recent interview she appeared to dismiss concerns about Kipling's colonial attitudes, and about a common perception that the Disney film's portrayal of a jazz-singing orangutan has racial overtones.

Jamil Khoury, the artistic director of Silk Road Rising, a Chicago company that produces works by Middle Eastern and South Asian writers, wrote a blistering blog post accusing Ms. Zimmerman of building her career on "Orientalism" and cultural appropriation.

Kipling's role as the foremost defender of the British Empire - and a certain queasiness about that singing ape - were on Ms. Zimmerman's mind as she approached "Jungle Book." She has built her reputation with adaptations of literary works like "Metamorphoses" and "The Arabian Nights," and had intended to draw heavily from the Kipling stories, but she found the music pulling her in the opposite direction.

"Once you commit to using the songs from the movie, they act like a dragnet: They pull in plot and character and, most importantly, tone," Ms. Zimmerman said. "I originally thought I was going to be using Kipling much more, but his tone is so radically divergent from the film that it would have no integrity to do that dark and bloody and vengeful version of things, and then do those songs."

The plot centers on Mowgli, an orphaned boy raised by wolves, then shepherded through pre-adolescence by Bagheera, a sagacious panther, and Baloo, a friendly bear, amid mortal threats from predators.

What might have been threatening got the Disney touch. "Walt told us, wherever there's a scary thing, turn it upside down and make it funny," recalled Mr. Sherman, now 85. So vultures sang a barbershop quartet with Beatles accents, and a plot point in which monkeys kidnap Mowgli was set to the scat-heavy "I Wanna Be Like You."

"We were thinking about Louis Armstrong when we wrote it, and that's where we got the name, King Louie," said Mr. Sherman. "Then in a meeting one day, they said, 'Do you realize what the N.A.A.C.P. would do to us if we had a black man as an ape? They'd say we're making fun of him.'

"I said: 'Come on, what are you talking about? I adore Louis Armstrong.'"

Louis Prima, an Italian-American, ended up doing the voice on the soundtrack, but the perception of racism has, for some viewers, stuck to the film. "I did hesitate about that song, but it's very curious," Zimmerman said. "Here are the elements: a drawn orangutan and Louis Prima's voice. Who's inserting the black person in there? There isn't one. The comparison is in the observer."

Casting the African-American polymath Andre De Shields in the stage role of King Louie could either complicate or transcend the role's race questions. Mr. De Shields naturally favors the latter view. "I've always said that part of my mission as a performing artist is a ministry to detonate stereotypes," he said.

Kipling, born in India, was shipped to a boardinghouse in England at 6. "He lost that paradise at essentially the age Mowgli is," Ms. Zimmerman said.

"I'm not an apologist for Kipling's toxic politics," she said. "But he's a very complicated figure with a big old wound in him that those books are compensating for."

The New York Times

(China Daily 06/30/2013 page12)