A sleight of hand conceals demolition

Updated: 2013-06-30 07:37

By Henry Fountain(The New York Times)

|

|||||||

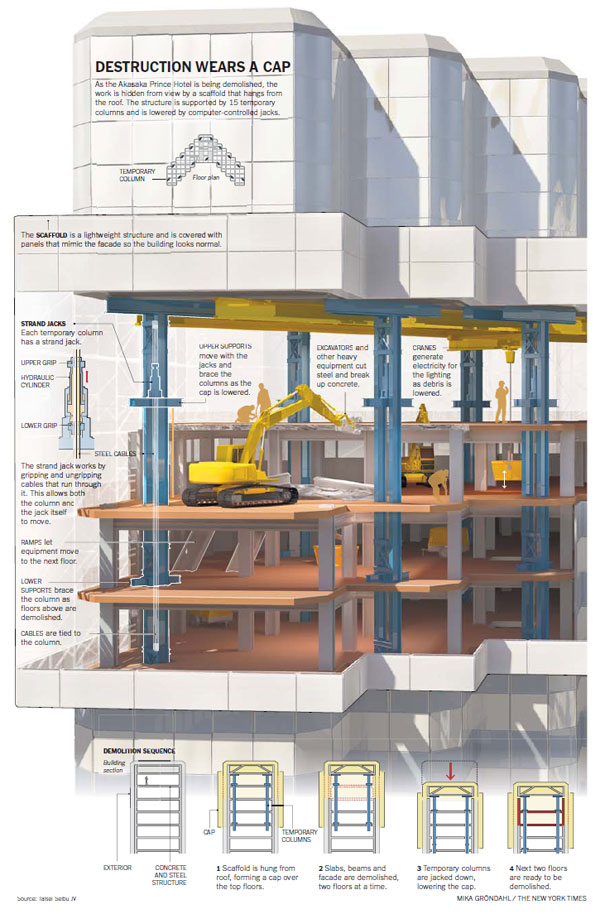

TOKYO - In this packed city with outdated high-rises and tough recycling and environmental restrictions, Japanese companies are perfecting what might be called stealth demolition. Some buildings are dismantled from the top, the work hidden by a moving scaffold; others from the bottom, the structure being slowly jacked down.

At times the techniques seem to defy gravity, for although the buildings appear intact, they slowly shrink. The methods, which make for a cleaner and quieter work site, may eventually find favor in other cities as aging skyscrapers become obsolete and the best solution is to demolish and rebuild.

The latest Tokyo high-rise to get the stealth treatment is the Akasaka Prince Hotel, a 40-story tower overlooking one of the city's commercial districts. Since last fall it has been torn apart floor by floor. It has been shrinking by about two floors every 10 days. It will be replaced by two new towers.

Hideki Ichihara, a manager with Taisei Corporation, which developed the system, said the technique had environmental benefits and allowed for more efficient separation of metal, concrete and other recyclable materials.

The hotel's top four floors were shrouded in a scaffold that hung from the intact roof and was covered in panels that mimicked the facade. When the two floors were gone, the roof-and-scaffold cap slowly descended.

The cap helps keep noise and dust down compared with more conventional methods of demolishing tall buildings, which involve erecting a scaffold all the way up and around the structure but leaving the top exposed.

"All the work is inside the covered area," Mr. Ichihara said. "The noise level is 20 decibels lower than the conventional way, and there's 90 percent less dust leaving the area."

Aside from the cap, though, the Taisei system is similar to other methods in that the structure is taken apart from the top down. Another Japanese company, Kajima Corporation, has developed a bottom-up approach, cutting a building's columns at ground level and jacking the structure down.

"The idea is to keep the building as intact as possible," said Ryo Mizutani, an official with Kajima, which in January finished demolishing a 24-story office tower, the Resona Maruha building, near the Imperial Gardens. Huge hydraulic jacks supported the building's 40 columns. Workers cut 75 centimeters from each column, over and over, to allow the structure to be lowered slowly.

By creating controlled work environments, both Japanese methods allow for on-site material separation for recycling. At the Akasaka Prince, Mr. Ichihara said, the sorting starts at the top, and the concrete and steel are brought down by separate cranes. With the Kajima bottom-up method, Mr. Mizutani said, all of the debris is created on the ground level, allowing for efficient sorting.

A 2002 Tokyo recycling law required that wood and concrete waste be recycled in addition to valuable metals like steel, aluminum and copper, even if the demolition contractors had to pay to do so.

"People started to take recycling seriously," said Tsuyoshi Seike, an associate professor at the Institute of Environmental Studies at the University of Tokyo. "And things have changed quite drastically with demolition."

Mr. Mizutani said his company's method had an added advantage in that hazardous materials like asbestos did not have to be removed from the site separately, before the structural demolition began. Rather, as the materials are stripped from each floor they can be left there until that floor reaches the ground and they can be safely carted away.

In earthquake-prone Tokyo, a building that is cut loose from its foundation could easily topple when the ground shakes. The company's solution is to build temporary concrete structures within parts of the building's steel frame. Locking devices that would activate in an earthquake would tie the frame to the concrete structures, presumably keeping the building stable.

Ordinarily, a building that is 30 or 40 years old should have many years of life left, if properly maintained. But the Tokyo buildings fell victim to a bull market for demolition.

"There are many ways to renovate," Dr. Seike said. "But with buildings in the middle of Tokyo, they think it's better to demolish."

The New York Times

(China Daily 06/30/2013 page11)