The art of hiding the loot

Updated: 2013-05-19 07:33

By Patricia Cohen(The New York Times)

|

|||||||

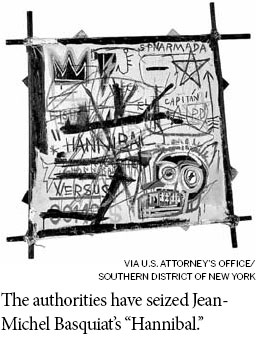

According to the air bill on the crate that arrived at New York's Kennedy International Airport from London, an unnamed painting worth $100 was inside. Only later did investigators discover that it was by the American artist Jean-Michel Basquiat and worth $8 million.

This painting, known as "Hannibal," was brought into the United States in 2007 as part of a Brazilian embezzler's elaborate effort to launder money, the authorities say.

The painting's seizure was a victory in the economy-rattling, billion-dollar fraud and money-laundering case of Edemar Cid Ferreira, a former Brazilian banker who converted some of his loot into a 12,000-piece art collection.

Law enforcement officials in the United States and elsewhere say "Hannibal" is just one of thousands of valuable works of art being used by criminals to hide illicit profits and illegally transfer assets around the globe. As other traditional money-laundering techniques have come under scrutiny, smugglers, drug traffickers, arms dealers and the like have increasingly turned to the opaque art market, officials say.

The Basel Institute on Governance, a nonprofit research organization in Switzerland, warned last year of the high volume of illegal and suspicious transactions involving art.

It is hard to imagine a business more custom-made for money laundering, with million-dollar sales conducted in secrecy and with virtually no oversight. What this means in practical terms is that "you can have a transaction where the seller is listed as 'private collection' and the buyer is listed as 'private collection,'" said Sharon Cohen Levin, chief of the asset forfeiture unit of the United States attorney's office in Manhattan. "In any other business, no one would be able to get away with this."

Governments around the world have taken steps to bring illegal activity to light. In February, for instance, the European Commission passed rules requiring galleries to report anyone who pays for a work with more than 7,500 euros in cash, and to file suspicious-transaction reports.

The United States similarly requires all cash transactions of $10,000 or more to be reported.

In a forthcoming book, "Money Laundering Through Art," the Brazilian judge who presided over the Ferreira case, Fausto Martin De Sanctis, argues for more regulation, saying if businesses like casinos and gem dealers must report suspicious financial activity, so should art dealers and auction houses.

But to dealers and their clients, secrecy is crucial to the art market's mystique and practice. The Art Dealers Association of America dismissed the idea that using art to launder money was even a problem.

In Newark, New Jersey, federal prosecutors in a civil case recently announced the seizure of nearly $16 million in fine art photographs as part of a fraud and money laundering scheme that prosecutors say was engineered by Philip Rivkin, a Texas businessman.

Mr. Rivkin, who has not been charged with any crimes, was last thought to be in Spain and had arranged to have the photos shipped there.

In New York, victims of the scams of the disbarred lawyer Marc Dreier are still in court fighting over art he bought with some of the $700 million stolen from hedge funds and investors. At the moment 28 works by artists like Matisse, Warhol, Rothko and Damien Hirst are being held by the federal government.

"Hannibal" also sits in storage. That 1982 Basquiat work was part of a spectacular collection that Mr. Ferreira assembled while he controlled Banco Santos in Brazil.

In 2004 Mr. Ferreira's financial empire, built partly on embezzled funds, collapsed, leaving $1 billion in debts. A court in Sao Paulo sentenced him in 2006 to 21 years in prison for bank fraud, tax evasion and money laundering, a conviction he is appealing. Before his arrest, however, art worth more than $30 million, owned by Mr. Ferreira and his wife, Marcia, was smuggled out of Brazil, Judge De Sanctis said.

According to court papers, "Hannibal" was bought for $1 million in 2004 by a Panamanian company called Broadening-Info Enterprises, which later tried to sell the painting for $5 million. It was sent to New York in 2007, passing through the hands of four shipping agents in two countries before landing at Kennedy International.

Since merchandise valued at less than $200 may enter the United States without customs documentation, duty or tax, "Hannibal," labeled as worth $100, was cleared for entry before the plane landed.

Philip Byler, Broadening's lawyer in New York, said the inaccurate invoices were just a shortsighted attempt by the art dealer that Broadening hired to save importation fees. "It was not done with the intention of smuggling," he said. He also challenged the Brazilian authorities' claim, saying that "Hannibal" was legally purchased from a company owned by Mr. Ferreira's wife.

Mr. Byler said that Broadening intends to appeal the forfeiture.

The New York Times

(China Daily 05/19/2013 page9)