Jazz's slim stepchild returns

Updated: 2013-05-12 06:20

(The New York Times)

|

|||||||

|

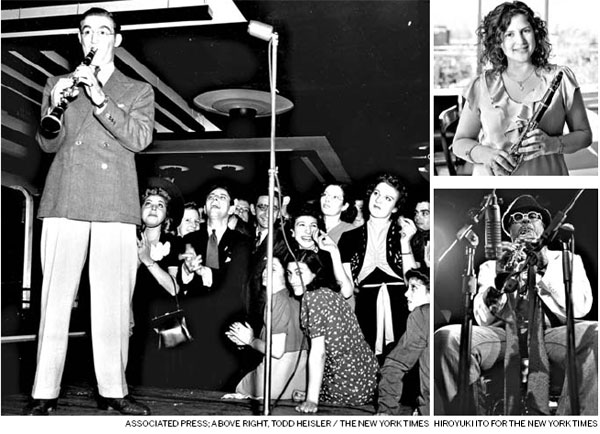

Benny Goodman, left, the clarinetist and band leader, performing in New York in 1938. Anat Cohen, top right, sees herself as a clarinetist first. Don Byron, a jazz reed player who focuses on the clarinet. |

In search of some live Brazilian music in New York a few months ago, I found my way to Dizzy's Club Coca-Cola, where the Brazilian percussionist Duduka Da Fonseca was leading a quintet that included Anat Cohen, a 38-year-old Israeli woman who lives in the city.

Around the fifth song, Ms. Cohen did something you rarely see a jazz reed player do these days. She took out her clarinet.

Like many jazz fans, I have rarely heard anyone play live jazz clarinet. A dominant instrument in jazz's early years, the clarinet faded into obscurity as the saxophone became the reed instrument of choice.

When you think of jazz clarinetists, only a handful of names spring to mind, including Benny Goodman and Artie Shaw, whose heyday was the 1930s.

But Ms. Cohen on the clarinet was a revelation. Using the clarinet's upper register, she could evoke infectious joy. In the lower register, her playing could conjure a deep, soulful melancholy. On up-tempo numbers, her improvisations had clarity and deep intelligence.

"When I play the clarinet, I am 100 percent myself," she later told me. "It is as if it is part of my body. I can play whatever I think. "

She said she took up the clarinet because the music conservatory she attended in Israel needed clarinet players. But as her tastes broadened, Ms. Cohen then fell under the sway of John Coltrane, the great 1960s tenor saxophonist. In high school, though, a teacher told her that her clarinet really didn't fit with the modern jazz she liked. "I kind of put a cap on my clarinet without really thinking about it," she recalled.

She became a committed tenor saxophonist instead.

But at Berklee College of Music in Boston, where she enrolled in 1996, she occasionally picked up the clarinet and remembers one of her professors telling her that she "really had a sound on the clarinet."

By 1999, she was the tenor saxophonist in an ensemble, called the Diva Jazz Orchestra. Then, she said, "somebody asked me to play clarinet on a choro gig."

Choro is a traditional Brazilian music that she describes as a kind of Brazilian ragtime. Her clarinet, with its quieter, higher-pitched sound, fit perfectly with the music, as it did with other kinds of Brazilian music, and world music, too.

"The clarinet," she said, "had a more traditional, folkloric sound. It was more normal to the ears."

After gigs, when people would come up to her to talk about her music, they would usually focus on her clarinet-playing.

By 2007, when she recorded her album "Poetica," Ms. Cohen had come full circle. Although she still played the tenor, she viewed herself as a clarinetist first.

When you ask music historians whatever happened to the clarinet, you get a variety of theories. The jazz critic Gary Giddins said that he thought the sound of the clarinet simply didn't blend well with the other instruments in postwar jazz.

Loren Schoenberg, the executive director of the National Jazz Museum in Harlem, thought it was something much simpler. "As the saxophone became more popular, by default, the clarinet became less popular," he said. Which is to say, it became uncool.

Now, in addition to Ms. Cohen, Ken Peplowski and Don Byron are two reed players who focus on the clarinet, while ensemble leaders like Maria Schneider often employ it in their orchestras.

Mr. Schoenberg praised Ms. Cohen's playing. "Because the instrument is so hard to play," he said, "many clarinetists fall into a kind of glib playing that shows off their technique. That is not how Anat plays. She can play all these different kinds of music, but she is always herself."

He called her brave.

"There is as much conformity in the jazz world as there is anywhere else," he said. "So for someone like her to actually be open enough to reconsider something as basic as her instrumental profile, that's very unusual."

The New York Times

(China Daily 05/12/2013 page12)