The life of a clammer: wet, nasty and brutish

Updated: 2013-05-05 07:36

By Kirk Johnson(The New York Times)

|

|||||||

OCEAN CITY, Washington - Some razor clammers take a methodical line, a slow, eyes-down stroll through the outgoing tide, watching for the divot that marks a clam's hiding spot, half a meter or so below the surface.

At age 82, John Lavender takes that approach. He walked the beach here on a recent morning with the cool calm of a clam digger's wisdom, born of 50 years' experience.

Then there's Garrett Lavender, 12, his grandson. For Garrett, digging razor clams is all about the charge, jump, dig, shout. The extended Lavender family drove six hours from their homes in south-central Washington to be here.

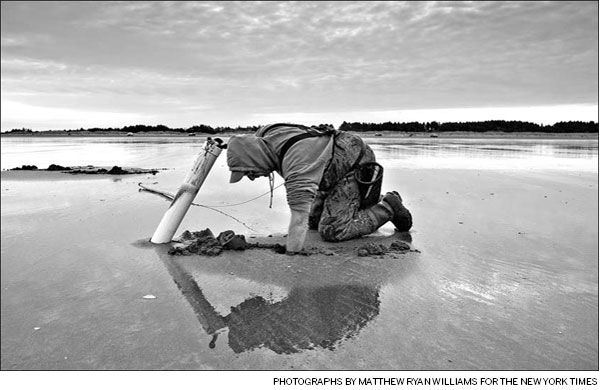

"They're faster than we are," Garrett said, slamming into the sand with his shovel. Moments later he was face down, arm deep into the hole, grasping for his prize before it could escape.

Pacific razor clams are sweet and meaty, a seasonal delicacy that finds its place in high-end restaurants in Seattle and Portland, Oregon, each two and a half to three hours away. They are also on the dinner plates of any recreational digger willing to buy a license and do some physical work in conditions that are sometimes cold and invariably wet. The season runs from October to May, with dates selected by the state based on clam stocks and when the low tides are right.

"I've been out here when it's rain and sleet mixed," said Mary Wyman, who came down from Whidbey Island, north of Seattle. Like most diggers, Ms. Wyman was using a clam gun - essentially a metal tube that, when shoved into the beach, pulls up a column of sand with a clam enclosed.

The relationship of humans and razor clams goes back thousands of years around here. The Indian tribes that dominated this part of the coast lived well, and also traded well with inland Indians who knew a good thing when they tasted it.

European settlement in the 1800s took clamming to an industrial scale (with a brief turn back to subsistence during the Great Depression of the 1930s when squatters lived on the beach in driftwood shacks).

Then starting in the 1960s, recreational clamming took off. According to state figures, clamming hit a peak in 1979 as a wave of scruffy outdoorsiness filtered through the Pacific Northwest culture.

John Gillespie, 75, a retired game warden who first began clamming here in 1967, said his 10-year-old granddaughter cannot get enough of the digging, and a 14-year-old grandson who could not care less.

He and thousands of Washingtonians still do it each spring and fall - buying a license and obeying the rules and the limit of 15 clams per day. But for many it is now more of an epicurean thing, or a nostalgic echo of a life lived closer to nature.

Mr. Lavender said he missed last season only because of chemotherapy. This year, though, he was not to be held back.

"He was bound to come," said his wife, Merle, 81, who was strolling the beach with her own clam gun. "And he's bound to get his limit, even if it takes all day."

The New York Times

(China Daily 05/05/2013 page10)