Finally, the bowl is in the spotlight

Updated: 2013-04-14 08:07

By Julie Lasky(The New York Times)

|

|||||||

|

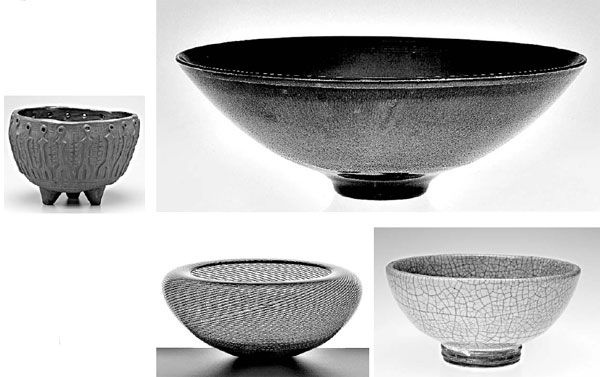

Clockwise from left: "Carved Pot" by Peter Voulkos; "Red Bowl" by James Lovera; "Untitled Yellow Crackle Bowl" by Glen Lukens; and "Purple Bowl" by Lino Tagliapietra. Photographs by Dan Kvitka / Museum of Contemporary Craft |

Last month, a small white ceramic bowl carved with a pattern of lotus blossoms sold for more than $2.2 million at auction in New York. That price was more than 700,000 times what the sellers had paid for it.

The consignors, whom Sotheby's identified only as a family from New York State, had bought the bowl for a few dollars at a yard sale in 2007. It was displayed in their home until they consulted Asian art experts and discovered that it was a thousand-year-old artifact from the Northern Song dynasty in China, an exquisite specimen of pale, thin-walled Ding pottery.

If it's curious that this Chinese bowl escaped notice for so long, it's an equal wonder that it came to light. Nothing signaled its age or rarity to the untutored eye.

Bowls haven't changed in any important way since the Song dynasty. In fact, they haven't changed much since the Neolithic era, between 4,000 and 10,000 years ago, when people first began making receptacles by hollowing out wood and stone or molding and baking clay.

Before the bowl, cupped hands and folded leaves brought water to the lips.

"We don't talk about the bowl because it's completely this everyday thing," said Namita Gupta Wiggers, director and chief curator of the Museum of Contemporary Craft in Portland, Oregon. "We take it for granted. We know it too well."

That so vital an article is overlooked led Ms. Wiggers to organize an exhibition devoted to it. "Object Focus: The Bowl" opened last month, displaying nearly 200 bowls, from a Tibetan singing bowl to a chrome ice bucket.

Ms. Wiggers said she was moved to think differently about the bowl after reading "The Language of Things," a book by Deyan Sudjic, who directs the Design Museum in London. Mr. Sudjic wrote about the ways designers have transformed ordinary household objects into coded luxuries meant to raise the owner's status and self-esteem. Such objects, as Ms. Wiggers interpreted it, include the table, lamp and chair. Consumers, she said, covet not just tables, but Noguchi tables; not just chairs, but Eames chairs; not just lamps, but Ingo Maurer lamps.

The bowl does not perform the same star turn in the object world, Ms. Wiggers believes, and she attributes its background role to its close connection with craft. The bowl has been overlooked partly because it's an accessory. Which is to say, it's a supporting player in the narrative of other objects and their users. What else is to be expected from something defined largely by the void at its center and its ability to contain a near-infinite variety of things?

"When I talk to people about the bowl, it is always about something else," Ms. Wiggers said. "It's a metaphorical conversation about ritual, like in the tea ceremony, or about the fabrication process. It's very hard to just talk about the bowl itself. We talk around the bowl."

Paradoxically, it's the bowl's lack of presence that makes it such an excellent metaphor and accounts for the many memorable references to it in literature. Sifting through the Western canon alone, one quickly arrives at Mr. Micawber and his punch bowl; Mrs. Dalloway's outre friend Sally Seton floating the heads of dahlias and hollyhocks in bowls of water; stately, plump Buck Mulligan performing a parody of the Roman Catholic Mass with a shaving bowl; and, of course, "The Golden Bowl" of Henry James. Tables, chairs and lamps can't begin to compete.

Ms. Wiggers has capitalized on the narrative richness of bowls by inviting scholars, writers and artisans to select an example from the show and write a brief essay about it. Some of the essays are philosophical, like the meditation by Mara Holt Skov, a curator in San Francisco, on a glass bowl by Do-Ho Suh modeled with the impression of the South Korean artist's cupped hands pressed into the base. It is, Ms. Holt Skov wrote, a "reminder that the hand is present in everything we make."

Take the ancient Song dynasty bowl that created such a stir: Tao Wang, who heads the Chinese art department at Sotheby's, said that the lotus pattern in the ivory bowl is probably a Buddhist allusion, symbolizing rebirth and purity. This particular bowl would have been used not for dining, Mr. Wang noted, but for making an offering to a temple. "It's not a simple daily object," he said.

Which is not to denigrate the everyday. "The simple bowl," Mr. Wang added, "is the great invention of the human mind."

The New York Times

(China Daily 04/14/2013 page12)