Nature's pretty, deadly drone

Updated: 2013-04-14 08:06

By Natalie Angier(The New York Times)

|

|||||||

|

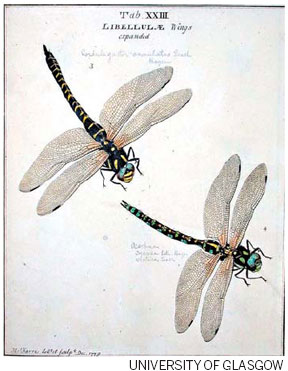

The brain, eyes and wings of a dragonfly allow it to hunt nearly unerringly. "An Exposition of English Insects" by Moses Harris, below, was published in 1782. Photographs by Jay Iwasaki / Combes Lab, Harvard University |

African lions roar and strut, but they're lucky to catch 25 percent of the prey they pursue. Great white sharks have 300 slashing teeth, and still nearly half their hunts fail.

Dragonflies, by contrast, look dainty, and they're often grouped with butterflies and ladybugs on the short list of Insects People Like. Yet they are also voracious aerial predators, and new research suggests they may well be the most brutally effective hunters in the animal kingdom.

When setting off to feed on other flying insects, dragonflies manage to snatch their targets in midair more than 95 percent of the time, often wolfishly consuming the fresh meat without bothering to alight.

"They'll tear up the prey and mash it into a glob, munch, munch, munch," said Michael L. May, an emeritus professor of entomology at Rutgers University in New Jersey.

Next step: grab more food. Stacey Combes, who studies dragonfly flight at Harvard University, once watched a laboratory dragonfly eat 30 flies in a row. "It would have happily kept eating," she said, "if there had been more food available."

In recent papers, scientists have pinpointed key features of the dragonfly's brain, eyes and wings that allow it to hunt so unerringly. One research team has determined that the nervous system of a dragonfly displays an almost human capacity for selective attention, able to focus on a single prey as it flies amid a cloud of similarly fluttering insects, just as a guest at a party can attend to a friend's words while ignoring the background chatter.

Other researchers have identified a kind of master circuit of 16 neurons that connect the dragonfly's brain to its flight motor center in the thorax. With the aid of that neuronal package, a dragonfly can track a moving target, calculate a trajectory to intercept that target and subtly adjust its path as needed.

The scientists found evidence that a dragonfly plots its course to intercept through a variant of "an old mariner's trick," said Robert M. Olberg of Union College in Schenectady, New York, who reported the research with his colleagues in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. If you're heading north on a boat and you see another boat moving, say, 30 degrees to your right, and if as the two of you barrel forward the other boat remains at that 30-degree spot in your field of view, vector mechanics dictate that your boats will crash: better slow down, speed up or turn aside.

In a similar manner, as a dragonfly closes in on a meal, it maintains an image of the moving prey on the same spot. "The image of the prey is getting bigger, but if it's always on the same spot of the retina, the dragonfly will intercept its target," said Paloma T. Gonzalez-Bellido, an author of the new report who now works at the Marine Biological Laboratory in Woods Hole, Massachusetts.

As a rule, the hunted remains clueless until it's all over. "Before I got into this work, I'd assumed it was an active chase, like a lion going after an impala," Dr. Combes said. "But it's more like ambush predation. The dragonfly comes from behind and below, and the prey doesn't know what's coming."

Dragonflies are able to hover, dive, fly backward and upside down, pivot 360 degrees with three tiny wing beats, and reach speeds of nearly 50 kilometers per hour. In the dragonfly, the four transparent, ultraflexible wings are attached to the thorax by separate muscles and can each be maneuvered independently, lending the insect an extraordinary range of flight options.

Their eyes are the largest and possibly the keenest in the insect world, a pair of giant spheres each built of some 30,000 pixel-like facets that together take up pretty much the entire head.

Dragonflies can't really hear, and with their stubby antennas they're not much for smelling or pheromonal flirtations.

Perhaps not surprisingly, much dragonfly research is supported by the United States military, which sees the insect as the archetypal precision drone.

Some dragonfly species migrate long distances. Recent studies have shown that green darner dragonflies migrate in sizable swarms each fall and spring between the northern United States and southern Mexico, while the globe skimmer dragonfly lives up to its name: it has been tracked crossing between India and Africa, a round-trip, multigenerational pilgrimage that may exceed 16,000 kilometers.

Dragonflies migrate to maximize breeding opportunities, to find warm freshwater ponds in which they can safely lay their eggs. From those eggs hatch dragonfly larvae: astonishing gilled predators that will spend weeks to years hydrojetting through water and shooting their mouthparts after aquatic prey, until they're ready to spread their wings and take the hunt to the sky.

The New York Times

(China Daily 04/14/2013 page9)