3-D printers at home

Updated: 2013-03-24 07:55

By Steven Kurutz(The New York Times)

|

|||||||

|

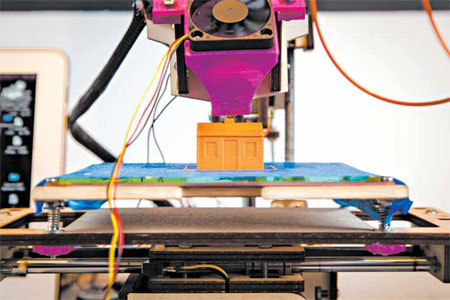

As the size and cost of 3-D printers decrease, the potential for uses at home increases. A Printrbot Jr. builds a tiny house with layers of plastic. Robert Wright for The New York Times |

|

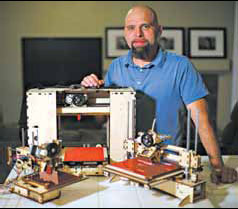

Brook Drumm is building a line of desktop 3-D printers. The company's goal "is a printer in every home and every school." Jim Wilson / The New York Times |

Brook Drumm, a bald, goateed father of three who lives outside Sacramento, California, has big aspirations for the Printrbot, a desktop 3-D printer kit he designed that, like a number of other 3-D printers, uses heated plastic - applied layer by layer to a heated bed by a glue-gun-like extruder - to turn designs created on a computer into real objects.

As Mr. Drumm illustrated in the Kickstarter campaign he used to raise more than $830,000 to start his business in late 2011, the Printrbot is small enough to fit on a kitchen counter, next to the coffee maker.

"The goal for the company," Mr. Drumm said, "is a printer in every home and every school."

The technology for 3-D printing has existed for years. But there is a growing sense that 3-D printers may be the home appliance of the future, much as personal computers were 30 years ago.

Like computers, 3-D printers originally proved their worth in the business sector, cost a fortune and were bulkier than a refrigerator. But less expensive desktop models have emerged, and futurists and 3-D printing hobbyists are now envisioning a world in which someone has an idea for a work-saving tool - or breaks the hour hand on their kitchen clock or loses the cap to the shampoo bottle - and simply prints the invention or the replacement part.

Bre Pettis, the chief executive officer of MakerBot, the New York-based company leading the way in making 3-D printers for the consumer market, has seen how the technology is already being applied. A file-sharing database MakerBot oversees, called Thingiverse, holds more than 36,000 downloadable designs.

"One of my favorite stories from Thingiverse is a dad who has a daughter who is 41 inches tall," Mr. Pettis said. "They were going to an amusement park, and she wasn't going to be able to go on any of the rides because the minimum height was 42 inches. The dad made orthopedic inserts for her shoes."

Last fall, MakerBot opened what may be the first retail store devoted to 3-D printers, in New York. Inside, demonstration models of the company's Replicator 2, a slick, steel-framed machine with the boxy dimensions of a microwave that sells for about $2,200, are constantly printing, turning files created on Trimble SketchUp and other computer-aided design (CAD) software into architecture models or smartphone cases.

Emmanuel Plat, director of merchandising for the Museum of Modern Art's retail division, said that in his experience, watching a 3-D printer work can induce future shock. "When people see the machine function, they're mesmerized," he said.

But for all the excitement surrounding 3-D printing, there is still a significant gap between its potential and the current reality. The 15,000 or so early adopters who have bought a MakerBot printer are mostly design professionals or hobbyists, not homeowners. And the things being printed still tend to be toys, key chains or just colorful pieces of plastic in amusing shapes.

Mr. Drumm bought a kit a couple of years ago. After assembling the machine, a complicated task that required a knowledge of soldering, he and his 6-year-old son printed a bottle opener. "It took 45 minutes and it was kind of crappy, but I was encouraged," Mr. Drumm said.

Mr. Pettis is betting parents will buy 3-D printers for their children in the same way his family purchased a Commodore 64 home computer in the early 1980s. The machines represent the future, he said, and "for the cost of a laptop" they offer "an education in manufacturing."

But at $2,200, a Replicator 2 costs more than most laptops, and one imagines families could find other uses for that money.

When he was designing the Printrbot, that was one of the things Mr. Drumm had in mind. He wanted the kit to be easy to assemble and to require no soldering, he said, but most of all he wanted it to be cheap. "It became obvious to me that it can't be $1,200 or even $800," he said. He settled on a price of about $550.

"People don't know what they're going to do with it," he added.

Max Lobovsky, one of the creators of the Form 1, a desktop 3-D printer that is stunning in both its design and printing quality, said the home 3-D printer is at a protozoan evolutionary stage. "It's not just about technology or reducing costs," Mr. Lobovsky said. "The machines need to be easier to use, more capable and offer more applications in the home. I think all of those things are missing today."

He and his partner, Natan Linder, envisioned the Form 1, which sells for around $3,300, as an affordable 3-D printer for professionals. Last September, they raised more than $2.9 million on Kickstarter, proof of the enthusiasm in the marketplace. They see 3-D printing technology working its way down from corporations to engineers, architects and crafters.

"There are a few more levels," Mr. Lobovsky said, "before we get to every single household."

The New York Times

|

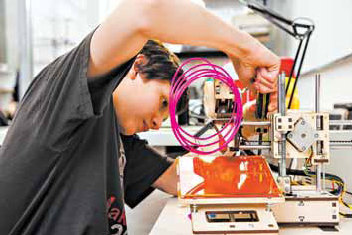

Matthew Duepner, 15, learned about 3-D printing at a workshop and "just fell in love with it." He tuned up his Printrbot Jr. at a club event. Robert Wright for The New York Times |

(China Daily 03/24/2013 page9)