Renewal, death and David Bowie

Updated: 2013-03-17 08:38

By Simon Reynolds(The New York Times)

|

|||||||

|

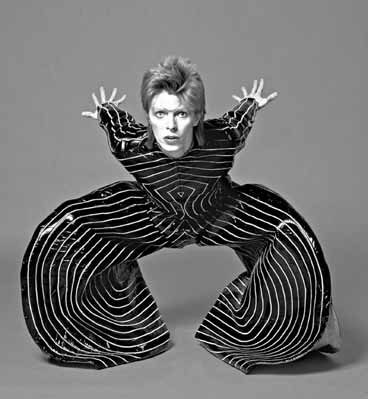

David Bowie, pictured in 1973, has ceaselessly reinvented his musical persona. Masayoshi Sukita / The David Bowie Archive 2012 |

On "The Stars (Are Out Tonight)," the new single from David Bowie's comeback album, "The Next Day," a line jumps out: "We will never be rid of these stars."

In the video, Mr. Bowie, 66, and the actress Tilda Swinton play an elderly couple persecuted by a pair of vampiric stars, who stalk them, invade their house and manipulate them like marionettes. But the song is less literal. It portrays celebrities as members of an overlord class who "burn you with their radiant smiles" but also as pitiable creatures, jealous of the grounded lives of ordinary folk. "But I hope they live forever," he sings, a nod to the notion of fame as immortality, a compensation for all the damage and delusion that comes with the territory.

Fame and death are closely braided themes shadowing "The Next Day," which is receiving acclaim as his strongest album in decades. Imagery of decay, debility and dejection pervade the record: "Here am I/Not quite dead/ My body left to rot in a hollow tree," he sings on the title track.

For most of the 21st century, Mr. Bowie had disappeared from view, even as the glam theatricality and gender-bending he pioneered was dominating pop through figures like Lady Gaga. Most assumed he'd retired, physically exhausted after a major heart attack and surgery in 2004, creatively spent after four decades of self-reinvention. But in a stealth attack, he returned in January with the wistful single "Where Are We Now?," the herald for "The Next Day," which came out on March 12.

The album, his first in a decade, asserts Mr. Bowie's relevance as a musician and songwriter. Dark in theme, "The Next Day" nods to high points in his past, notably "Lodger," from 1979, but the lyrics are unusually direct and unflinching for an artist who has often hidden behind masks or wrapped bleakness in obliqueness.

Meanwhile, his stature in pop history as the performer who bridged the gap between art and rock is being shored up by "David Bowie Is," a retrospective opening March 23 at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, a celebration of his mastery of all the nonaudio aspects of pop, including clothes and record artwork.

Among Mr. Bowie's most famous pronouncements early in his career were "I feel like an actor when I'm onstage, rather than a rock artist," and "If anything, maybe I've helped establish that rock 'n' roll is a pose." Before he came along, there was supposed to be a more-or-less direct correspondence between the performer and his real-life personality. But Mr. Bowie talked about playing characters, such as the rock god Ziggy Stardust, or the cold, remote Thin White Duke. He was the same and yet different each time he came before the public with a new album and tour.

In the mid-'60s, he hopped through five bands and many styles and looks before connecting with the public around 1969. Once his career took off, the shape-shifting took on a new urgency. He circumvented pop's cruel turnover by turning himself into the New Thing, again and again. As he said in 1977: "My policy has been that as soon as a system or process works, it's out of date. I move on to another area."

Mr. Bowie's great precursor and influence was Andy Warhol, the inspiration for his 1971 song "Andy Warhol." Analyzing Warhol, the art critic Donald Kuspit wrote of "the protean artist-self with no core" - a description that could also fit Mr. Bowie.

Read the vintage interviews, and it's striking how often intimations of hollowness occur, the sense of a man who appears superconfident but who battles feelings of self-loathing and doubt. "When I saw a quality in someone that I liked, I used it later as if it were my own"; "I'm not an innovator. I'm really just a Photostat machine. I pour out what has already been fed in." It seems as if "a continuing, returning feeling of inadequacy over what I've done" has helped propel the restless remaking of sound and style.

Warhol "superstitiously believed" that fame could keep death at bay, Mr. Kuspit says. When Mr. Bowie declares, "I hope they live forever" in "The Stars," is this a gesture of solidarity with "the dead ones and the living"?

You can reinvent yourself over and over, but Death, the Great Uninventor, will catch up. The torment of that unease has fueled Mr. Bowie's twilight masterpiece.

The New York Times

(China Daily 03/17/2013 page12)