A fascination with wood

Updated: 2013-03-10 08:01

By Zhao Xu(China Daily)

|

|||||||

|

An independent scholar of traditional Chinese culture, Mi Hongbin has a soft spot for wood. Wang Jing / China Daily |

Old wood is valued in China for its aged patina, its markings and a beauty that lives on long after the tree was felled. Zhao Xu talks to a scholar who has made it his calling to study and treasure wood.

Mi Hongbin raised his very first question about wood at the age of 7 as he watched a traditional Chinese doctor take his patient's pulse.

"What he did, basically, was to place his fingers gently on the patient's wrist and count the throbs," says Mi, an independent scholar with a special bent for the mystical and philosophical aspects of Chinese culture, and a soft spot for wood.

But it was the prop, not the healing that held the young man's attention.

"What intrigued me was not that he could come to a diagnosis through such a simple but mystified procedure, but the fact that it couldn't be performed without that small chunk of wood, on which the patient rested his wrist."

That "chunk of wood" has been part of the healing paraphernalia for ages, and is known as a "pulse pillow". Many have been used for decades, and all have been polished by constant use to a shiny patina, oiled by numerous encounters with human skin.

"To a child like me, it was a symbol, an essential part of a ritual," Mi recalls. "And I asked my father: 'Why wood? Maybe we could use something else, like a cotton-stuffed real pillow?'"

His answer was brief, but it took Mi the rest of his life to decipher the words.

"Wood cultivates people", his father had said.

Shouldn't it be the other way round, Mi had thought at the time. The question remained in Mi's head as extensive travels around the country drew him deeper and deeper into the study of wood, much like the concentric swirls that marks a tree's core.

"For the Chinese, wood represents two things: constancy in the face of a fickle world, and gentleness bestowed by age," says Mi.

As proof, he points to Beijing's Forbidden City, the site of the royal palaces and the seat of power for nearly half a millennium. This is where every pillar and chair is a marvelously constructed wooden wonder that once spoke well of an everlasting and benign rule.

"On another level, the qualities believed embodied in wood are exactly the ones traditional culture valued - a steadfast inner depth and a suave exterior," Mi says.

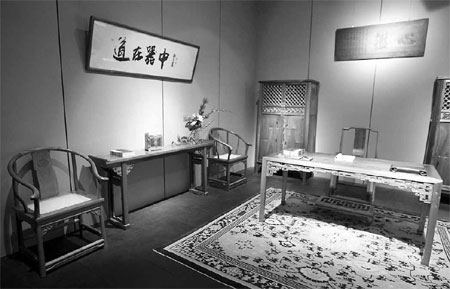

Mi has just finished consulting for an exhibition of wooden furniture at Beijing's National Museum called Beauty Honored by Time.

More than a hundred pieces were showcased, both ancient and modern, and all were made from a rare slow-growing wood called jinsi nanmu or golden phoenix wood, valued for its amber color, rippling grain and sweet, soothing scent.

It was in the dimly lit, wood-scented exhibition hall that Mi found the perfect examples to illuminate his thoughts.

"The Chinese attitude toward wood can only be fully understood in the context of their age-old furniture-making traditions," says Mi, pointing to a wooden latticed boudoir bed.

The different parts of its intricately repetitive floral patterns were pieced together by the mortise-and-tenon method, a technique deeply rooted in the country's ancient philosophy.

"The mortise (sun, ) and tenon (mao, ) symbolize yin and yang, the dual forces that rule our natural world and give expressions to all its simultaneously contradictory and interdependent phenomena, such as female and male, water and fire, life and death," explains Mi. "We Chinese believe that enduring beauty could only be achieved through embracing this duality."

Iron nails may rust and screws may come loose but a mortise and tenon fuse into each other for all seasons.

If the idea of yin and yang appears a little too abstract for those born and raised outside of Chinese culture, the many details diligently worked into Chinese wooden furniture can paint a more vivid picture for them, sometimes with an unexpected dash of humor.

An example is the trapeze-shaped book cabinet whose double doors would gradually and automatically close after being opened. The name of the cabinet, "a lazybones' cupboard", tells only half of the story.

"The cabinet had been especially designed for scholars who were presumably interested in nothing but burying their noses in classics and often absent-minded beyond the pages," Mi says. "With its doors designed thus, a lazybones' cupboard offered protection to the beloved books that may be otherwise neglected by their absent-minded owners."

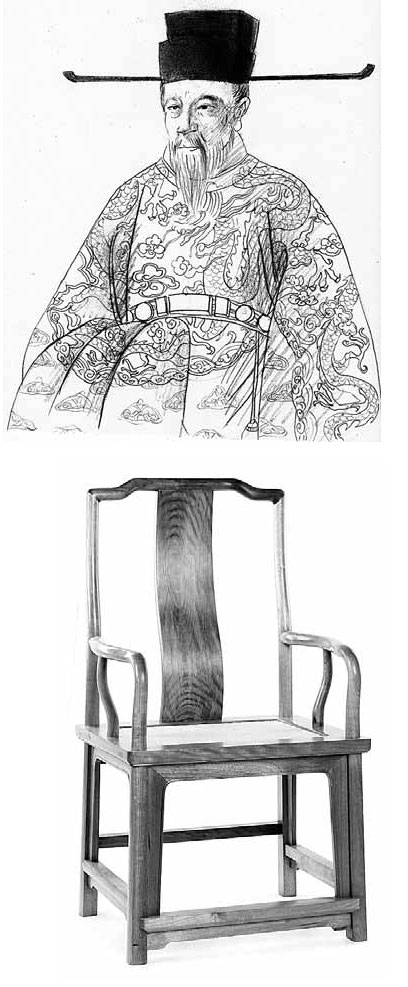

Forgetful or not, the scholars were often single-minded about one other thing, and that was to study hard so they could rise above the rest and earn a position in court. This craving for that high office is manifested in a common piece of furniture in the study - dubbed the "official's hat chair".

"During the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644), officials wore a certain headgear with tight-fitting black cap with two extended wing-like flaps," explained Mi. "When one sits on an official's hat chair, the top rail of the chair's S-shaped backrest extends from both sides of the head like wings on an official's cap."

The message is very clear - study hard and aim high.

If there is one particular group traditional Chinese wood culture attracts, it is the literati class whose members have been a highly introspective breed, judging by the furniture pieces they have inspired.

However, according to Mi, the ultimate proponent and practitioner of the country's furniture-making tradition was no bookworm or wallflower but someone who acted on power and will. He was Zhu Youxiao, the 15th emperor of the Ming Dynasty who reigned briefly from 1620 to 1627.

Known as the "Carpenter Emperor", Zhu had apparently found more personal fulfillment with a carpenter's saw than an emperor's seal.

He spent most of his day sweating in the court workshop, and the young emperor craved recognition from his peers and the market, like most serious artisans. At his order, completed pieces were taken outside the palace to be sold at local markets.

One man's obsession has spawned a trend. Carpentry was increasingly viewed as an artistic pursuit, and a noble engagement. Celebrated personalities of the time made and signed their furniture pieces the same way they placed their seals on paintings and calligraphy works.

The dominant style formed during this period, famously known as the "Ming Style", eschewed any superfluous decoration for a deliberate minimalism, or an understated luxury to use the modern lexicon.

"The style is a direct reaction to all the sumptuousness of the preceding era, and is underwritten by the belief that while sophistication exacts the eye, simplicity trains the mind," says Gao Shuzhen, founder of the Nanmu Studio which is behind the National Museum show.

"And that ideal triumphed during the Ming Dynasty."

Although style temporarily yielded to a much more elaborate and ornate aesthetic during the Qing Dynasty (1644-1911) which followed, "Ming Style" has reinforced itself as the current paragon of classical Chinese furniture-making especially as modern collectors and connoisseurs initiated a society-wide search for "our cultural roots".

As for his father's sage saying about "wood cultivating people", the 41-year-old Mi has finally arrived at his own conclusion.

"A master carpenter and his chosen piece of wood - they both have their own temperaments. The relationship between them can be best described as a love affair. The craftsman is determined to turn natural beauty into a work of art with timeless appeal, investing countless hours of hard work and total concentration of mind and soul," Mi says.

"By doing so, he brings out the best in himself and becomes complete."

Contact the writer at zhaoxu@chinadaily.com.cn.

|

A Ming-style study: Four Chinese characters in the calligraphy work are dao zai qi zhong, or "wisdom in what you use". Photos by Wang Jing and Provided to China Daily |

|

Top: A Ming Dynasty official wore a tight-fitting black cap with two extended wing-like flaps. Above: An official's hat chair, the top rail of the S-shaped backrest extends both ways like wings of an official's cap. |

|

A latticed boudoir bed flaunts intricately repetitive flower patterns made using mortise-and-tenon joints. |

|

The four parts of the floral motif are interlocking pieces. |

(China Daily 03/10/2013 page1)