Stitches from time

Updated: 2013-02-24 08:27

By Wang Ru(China Daily)

|

|||||||

|

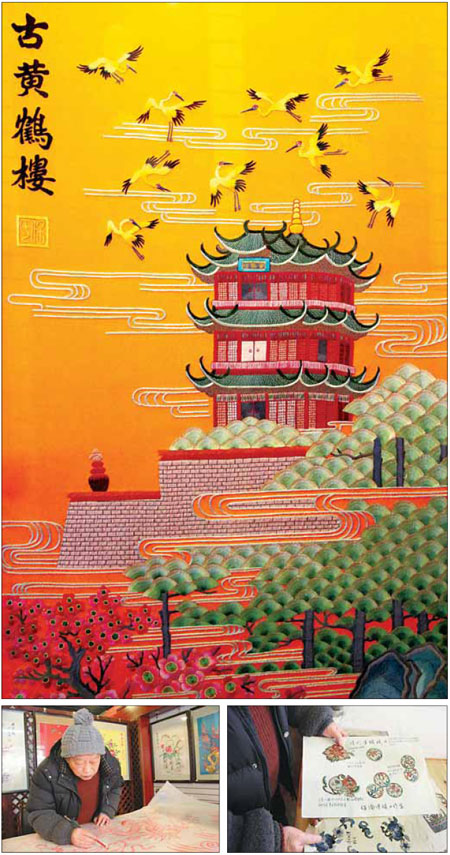

Ren Benrong works on embroidery designs in his studio. One of his works, Yellow Crane Tower, or Huanghelou (above) features a historic landmark in his hometown of Wuhan. Photos Provided to China Daily |

Embroidery is part of the Chinese cultural fabric, and there are many schools with unique stitches, designs and characteristics from various regions. One of the most long-lived is Han embroidery, from the central plains, which dates back to beyond 2,000 years. Wang Ru talks to a guardian of the ancient art.

When Red Guards broke into his home during the "cultural revolution" (1966-76), they destroyed more than 200 pieces of embroidery that Ren Benrong had in his collection. He stood aside and watched. As Ren, now 78, witnessed them burn the centuries-old elegant handcrafted work that he had inherited from his father and grandfather, he could not hold back his tears of anguish, but he also felt relieved of a heavy burden. "Most the embroideries were from theatrical costumes of plays about emperors and imperial families, all in the deeply-hated category of 'feudalism's evil legacy' then," Ren explains.

Decades later, he is sitting in his new embroidery studio in a cultural heritage community in Wuhan, capital of Central China's Hubei province, where he had moved to in August last year. He is master of more than 200 apprentices, all here to learn the ancient art of Han embroidery.

It is a style that originated in the ancient state of Chu during the Eastern Zhou Dynasty (770-256 BC), in what is now central China, along the hinterlands of the Yangtze River.

Han embroidery is known for its rich colors, bold designs and fine techniques. Many samples of Han embroidery were discovered in excavated tombs dating from 2,000 years ago.

Legends surround the art, some from the Romance of the Three Kingdoms, a collection of stories from the late Han periods.

It is said that Liu Bei, the warlord of late Eastern Han Dynasty (AD 25-220) was about to face his nemesis Cao Cao, a powerful enemy from the north who intended to invade with a mighty army.

Liu ordered all the women in his city to make brightly embroidered battle flags that would line the city walls.

Awed by the display, Cao suspected an ambush and withdrew his forces. Thus was the embroidery needle proved mightier than the battle-axe.

Back to modern times, Ren, our Han embroidery master, was born and raised on a 400-year old "Embroidery Street" in Hankou, Wuhan, where thousands of embroidery specialists used to practice their art in about 40 or so shops run by merchant families. Their work was exported all over China then.

Ren comes from a family of expert designers on the street. While the actual embroidery was mostly done by women, the designs were only crafted by men, who traditionally passed on their knowledge only to sons, not daughters.

A qualified Han embroidery designer needed to master not only the complicated needlework techniques of Han embroidery, but also the design and tailoring styles of royal costumes from different dynasties, and they needed knowledge of folk culture, Taoism and painting skills.

At the peak of its popularity, the War of Resistance against Japanese Aggression broke out in 1937 and lasted till 1945, and American bombers razed the whole street, which was near a Japanese arsenal in occupied Hankou.

"The business was destroyed overnight. Most shop owners and workers fled to the countryside," Ren remembers.

But genes would tell, and Ren could not abandon the family heritage.

Ren had been primed in all the knowledge of embroidery design since he was a child. At 12, he was apprenticed for three years, followed by one year as an assistant designer and another five years learning from an embroidery master.

"Embroidery requires great patience. It takes two months to finish a piece, and it involves complex processes of designing, the matching of colors, and the execution of millions of stitches. An exquisite work may take more than half a year to complete."

For years, Ren worked 18 hours a day to perfect his craft, hands and ears often frozen in the harsh winter. In 1957, he left Hankou for Beijing to study at the new Central Academy of Craft Art.

In his two years in Beijing, Ren soaked up knowledge of traditional Chinese folk customs and deepened his understanding of culture theories. He also did research on imperial costumes in the Forbidden City.

When he returned to Wuhan, he started work with a company that produced theatrical costumes and one of the works he helped produce - eight embroidery pieces of places of interests in Hubei - were selected for display at the Great Hall of the People in Beijing.

But in the 10-year chaos of the "cultural revolution", his company closed down, and Ren became a boiler worker, shoveling coals into furnaces.

Even then, Ren did not give up his art and secretly kept in practice under the cover of night. He also took a risk and went back home, raking through the pile of the ashes left by the Red Guards and salvaging what he could of the destroyed embroidery.

When that dark era finally ended, Ren returned to work at another theatrical costumes company, and slowly realized that there might still be a bright future ahead for Han embroidery.

He kept this vision even after he retired in 1990, and started his quest across Hubei, collecting more than 2,000 samples of Han embroidery, some of which were faded fragments.

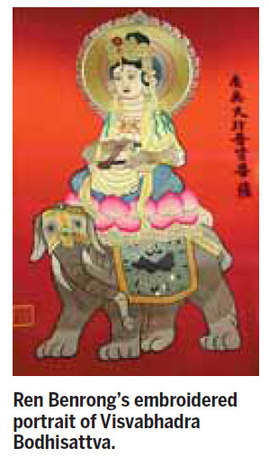

Ren then invested his life savings to buy the silks and threads from Suzhou, Jiangsu province and started restoring the most traditional skills of Han embroidery. His works are now collected at the Wuhan Museum and are often given as cultural gifts from the State to distinguished foreign visitors.

In 2008, Han embroidery was listed as a National Intangible Cultural Heritage of China and Ren was acknowledged as a living inheritor of the traditional art. In August last year, with the full support from the local government, Ren was allocated a large rent-free studio to continue his work.

Ren hopes to establish a Han embroidery museum, and publish a book that summarizes the skills and knowledge so more people will understand the ancient art.

"I gave my life to embroidery because I respect my ancestors, the tradition and the history, it is in every stitch of my work," he says. But there is one thing that places him apart from past masters. Ren has decided to pass on his skills to his daughters and granddaughters.

Contact the writer at wangru@chinadaily.com.cn.

(China Daily 02/24/2013 page1)