Cuban surfers overcome obstacles before waves

Updated: 2013-02-24 07:52

By Nick Corasaniti(The New York Times)

|

|||||||

|

Photographs by Jose Goitia for The New York Times |

|

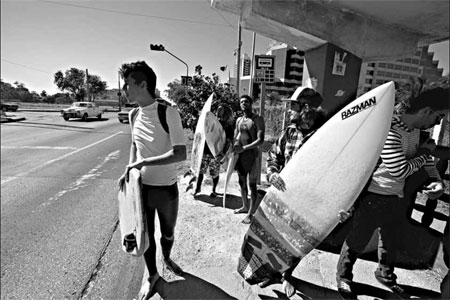

Government officials once feared surfers would leave Cuba on their boards. Hurdles for surfers include a lack of real surfboards. |

HAVANA - Eduardo Valdes peered out over Playa, past the embassies of Miramar, to the glimmering royal blue of the distant Straits of Florida, searching for a hint of white rolling eastward.

"This is my surf report," said Mr. Valdes, who, with his hair pulled into a bun and tattoos emerging past the hem of his board shorts, looks almost as Hawaiian as he does Cuban. "And it's flat again. Where are my waves?"

The waves will come, up to two meters the next day, but for Cuba's surfers the other staples of the sport are hard to come by. Surf wax, new boards or simple online surf reports are scarce. Cuban policies, and the American blockade, have made surfing here a complicated endeavor.

But the sport persists in Cuba through the determination of native surfers and homegrown organizations like Royal 70, a nonprofit surf collective founded by Mr. Valdes and Blair Cording, an Australian surfer.

"I started surfing by intuition," said Frank Gonzalez, 26. "Then, after surfing for four years, I saw my first surf video. Wow, I was impressed."

For years, having a modern surfboard in Cuba was as rare as having a passport. Most surfers had to use crudely shaped pieces of plywood, often ripped from discarded school desks and coated in black-market resin. Those who found a sizable piece of wood would staple a makeshift wood fin to the bottom and attach clothesline for a leash.

The lucky few to encounter a discarded refrigerator at a junkyard stripped it of its yellow foam and shaped a board using cheese graters and coat hangers - the closest thing a Cuban could get to a modern polyurethane board. Fiberglass scavenged from boatyards and shipwrecks coated the refrigerator foam but made it heavy. But as refrigeration technology changed, finding even the yellow foam became difficult.

Adding to the challenge is the danger of surfing Havana's main break, Calle 70. The waves peel across a razor-sharp reef dotted with sea urchins; most wipeouts end in blood.

"It's probably the scariest place I've ever surfed," said Mr. Cording, 42, who sold everything he owned to travel to Cuba to bring donated boards.

Cuba's sports infrastructure is similar to the one in the former Soviet Union, where officially recognized sports like baseball and boxing receive financial support, coaching and backing by the state government. Surfing is not only unrecognized here, but the concept of Cubans swimming away from protected shores with a flotation device can also leave officials uneasy.

According to Cuban lore, the first surfers in Baracoa were thrown in jail. "When the cops released them, they told them, 'Get your boards and go back to Havana,'" Mr. Valdes said, adding that the authorities thought the surfers were trying to leave the country.

To help improve surfing's image, Mr. Valdes and Mr. Cording organized good-will missions. Last Christmas, Mr. Valdes brought $800 of food and goods to a Havana orphanage with money raised in Australia. Havana surfers also organize beach cleanups. And they continue surfing without creating problems for government officials.

"The government struggles with the idea of surfing," said Mr. Cording, who works with Cuba's sports ministry to negotiate the flow of donations. "They said do it underground and we'll turn a blind eye."

Cuba has more than 3,700 kilometers of coastline (California has about 1,350 kilometers of beaches). Yet the surfing Web site Surfline, which provides reports of known surf spots, lists only four breaks on the island.

For Mr. Valdes, the problems facing Cuba's surfers could be helped with one change.

"I just want someone to come and make a surf shop here, at least with wax and leashes and maybe rashguards," he said. "We could be sustainable. That would be enough."

The New York Times

(China Daily 02/24/2013 page10)