With 'Hobbit,' New Zealand fuses film and tourism

Updated: 2012-12-09 08:09

By Michael Cieply and Brooks Barnes(The New York Times)

|

|||||||

|

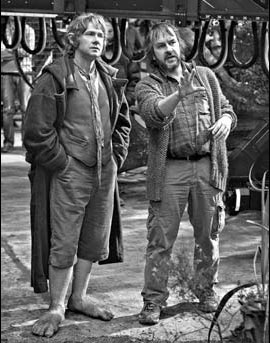

The director Peter Jackson, far right, used sites in New Zealand to film "The Hobbit." Gollum at Wellington Airport. Marty Melville / Agence France-Presse - Getty Images; below, Todd Eyre / Warner Brothers Pictures and MGM |

WELLINGTON, New Zealand - In Prime Minister John Key's office is a sword given to him by President Obama. It was used, he said, by Frodo Baggins in the "Lord of the Rings" trilogy, and it serves as a reminder that in New Zealand, the business of running a country goes hand in hand with the business of making movies.

Mr. Key's government has taken extreme measures that have linked its fortunes to some of Hollywood's biggest pictures, making this country of 4.4 million people a grand experiment in the fusion of film and government.

As "The Hobbit: An Unexpected Journey," the first of three related movies by the director Peter Jackson, approached its world premiere on November 28 in Wellington (and in December worldwide), there were signs everywhere of the film's integration into Kiwi life- from the giant replica of its Gollum creature at Wellington Airport to the gift shops that are expanding to meet anticipated demand for Hobbit merchandise (elf ears, $14).

But the path to this moment has been filled with controversy. Two years ago, when a dispute with unions threatened to derail the "Hobbit" movies- endangering several thousand jobs and a commitment of some $500 million by Warner Brothers- Mr. Key persuaded the Parliament to rewrite its national labor laws.

The government agreed to contribute $99 million in production costs and add $10 million to the studio's marketing budget. And its tourism office will spend about $8 million in its current fiscal year, and probably more in the future, as part of a promotional campaign to market the country as a film-friendly fantasyland.

For tiny New Zealand, where plans to cut $35 million from the education budget set off national outrage this year, the "Hobbit" concessions were difficult for many to accept, especially since the country had already provided some $150 million in support for the "Lord of the Rings" movies.

And recently the government has been suspected of taking cues from America's powerful film industry in handling a request by United States officials for the extradition of Kim Dotcom, the mogul whose given name was Kim Schmitz, so he can face charges of pirating copyrighted material.

Mr. Key has been sharply criticized for cozying up to Mr. Jackson, a fellow New Zealander. Phil Darkins, a vice president of Actors Equity in New Zealand, calls his country the "only Western democracy on the planet where professional performers have virtually no rights."

Mr. Darkins also objected to immigration law changes that allow foreign film workers into the country for brief periods without review by local worker groups.

The opposition Labour Party, while backing the government's support for the film industry, has chafed at what it views as the "Warner Brothers-specific" concessions made by Mr. Key.

The making of feature films and TV shows generated only about $1.1 billion in revenue for New Zealand last year, well under 1 percent of a gross domestic product of roughly $160 billion. About 17 percent of movie and TV revenue is directly subsidized by the national government, which spent nearly $200 million to support movies last year.

But the tourism industry is 20 times the size of the country's movie and television production business. And as other countries, notably China, have moved into some of New Zealand's core dairy industry, the Kiwis have focused more on the vacation market.

The thinking: Movies may draw visitors who are not up to the rigors of bungee-jumping, zorbing (rolling downhill inside a plastic ball) or other outdoor sports that are tourism mainstays.

Scratching for solutions to the 2010 crisis with unions over "The Hobbit," Mr. Key, who is also the tourism minister, settled on using much of the tourism budget to re-brand the country as Middle-earth, hoping to lure visitors to Mr. Jackson's film locations.

But there is no guarantee moviegoers will embrace the "Hobbit" films with the same fervor as the "Rings" trilogy, with combined global ticket sales of $3 billion.

Other big questions remain, including the capricious nature of the filmmaking business, which will quickly flee to the government offering the best incentives.

Exchange rates play a sizable part in the bidding process. Favorable rates were one reason Mr. Jackson and his partners were able to build New Zealand into a crossroads for special effects and postproduction work. "Avatar," "Marvel's The Avengers," "The Adventures of Tintin" and "Prometheus" are among the many films that have crossed through Mr. Jackson's Wellington-based effects shop, Weta Digital, on their way to theaters.

But recently a stronger New Zealand dollar has eroded its cost advantage for North American companies. Northern Ireland now claims to be the "new New Zealand," while Serbia says it is "New Zealand, but cheaper," notes Gisella Carr, chief executive of Film New Zealand, which scours the globe for film work.

Hollywood is also looking to China, where the government is building expensive movie facilities and offering access to a vast market in exchange for a stake in American studio pictures.

New Zealand does have language in its favor, since the crews speak English. Still, for Mr. Key and others, the primary challenge remains linked tightly to Mr. Jackson: how do you build a significant and enduring economic sector from a local business dominated by one man?

"You can't base an industry solely on one person," said Mr. Key. "That's a very vulnerable business strategy."

Smaller filmmakers say the priority given to big productions like Mr. Jackson's has hurt them. In Auckland, where an independent film culture once thrived, Mr. Jackson is acidly referred to as "Sir Peter," emphasizing the honorific he received in 2010.

Mr. Jackson, 51, disagreed with the notion that New Zealand's film industry rested squarely on his shoulders. "If I started to think like that my head would explode," he said. "I can't take responsibility for everyone's employment."

He does, however, employ thousands. His Stone Street Studios include four soundstages, two sophisticated enough to allow him to construct a rushing river inside, as "Hobbit" scenes required. A few blocks away, Weta Digital employs a thousand graphic artists, technicians and support staff. Also nearby is the 300-employee Weta Workshop, which builds props, designs film-related merchandise and fills private orders for rich collectors- like a full-size working Panzer tank.

The collection of companies takes up so much space it has been given a nickname: Wellywood.

As "Lord of the Rings" tourism peaked in recent years, about 6 percent of international visitors to New Zealand, or roughly 150,000 people, cited the films as a reason for coming; 11,200 said it was their only reason.

As Mr. Key explained, "Peter is a very, very big fish in quite a small tank."

The New York Times

(China Daily 12/09/2012 page12)