Holding back floods with balloons

Updated: 2012-12-02 07:59

By Henry Fountain(The New York Times)

|

|||||||

|

Hurricane Sandy brought a storm surge into New York City's subways. Patrick Cashin / Metropolitan Transportation Authority |

MORGANTOWN, West Virginia - With a few dull thuds, the 900-kilogram bag of high-strength fabric tumbled from the wall of the mock subway tunnel and onto the floor. Then it began to grow.

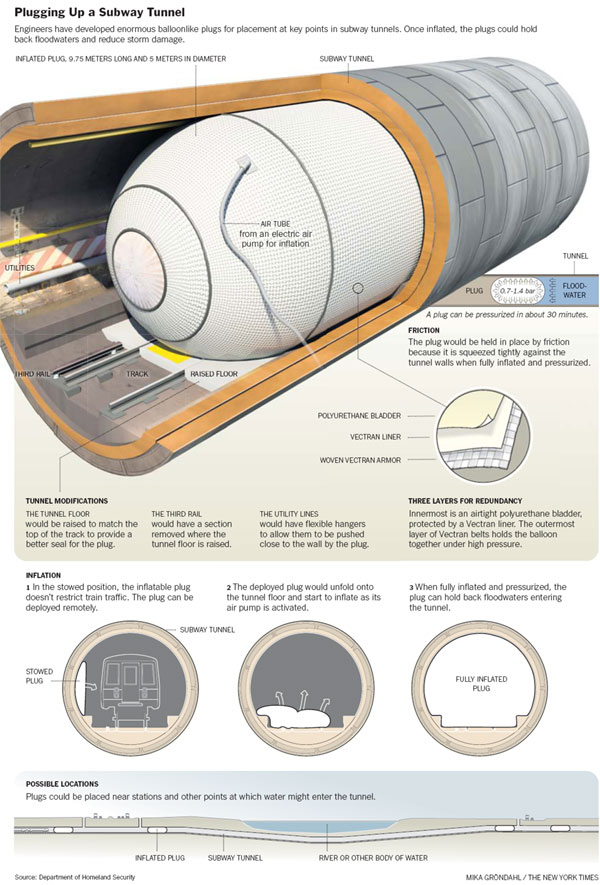

As air flowed into it through a hose, the bundle inflated until it was crammed tight inside the five-meter-diameter tunnel, looking like the filling in a giant concrete-and-steel cannoli.

The three-minute procedure was the latest test of a device that may someday help guard real tunnels during disasters - whether a terrorist strike or a storm like Hurricane Sandy, whose wind-driven surge of water overwhelmed New York City's subway system in October.

"The goal is to provide flooding protection for transportation tunnels," said John Fortune, who is managing the project for the United States Department of Homeland Security's Science and Technology Directorate.

The idea is a simple one: rather than retrofitting tunnels with metal floodgates or other expensive structures, use a relatively cheap inflatable plug to hold back floodwaters.

But developing a plug that is strong, durable, quick to install and foolproof to deploy is a difficult engineering task.

"Water is heavy, there's a lot of pressure," said Greg Holter, an engineer with Pacific Northwest National Laboratory who helps manage the project. "So it's not as simple as just inflating and filling the space. The plug has to be able to withstand the pressure of the water behind it."

The idea has been in development for more than five years and Dr. Fortune says there are at least a few more years of testing and design work ahead.

If the plugs are shown to be effective, they will be made available to transit systems around the country; they are expected to cost about $400,000 each.

Work on the plug began in 2007, after Ever J. Barbero, a West Virginia University professor whose specialty is the use of advanced materials in engineering, was contacted by a Homeland Security official looking for unusual ideas on ways to keep a subway system from flooding if an underwater tunnel were breached - by a terrorist bomb, for example.

"I said, 'We'll put an air bag in a tunnel,'" Dr. Barbero recalled. About $8 million has been spent on the project so far.

The first full-scale plug, made with a single layer of Vectran, a strong but lightweight yarn spun from a liquid-crystal polymer, failed during a pressure test in 2010. "It ripped right down the middle," Dr. Fortune said.

So Dr. Barbero and ILC Dover, a company in Delaware that makes high-strength soft structures like spacesuits, came up with a three-layer plug, with the outer layer consisting of woven Vectran belts.

"It took time to figure out how to make it work with such huge pressure," Dr. Barbero said. "But it also took time for the team to understand how a subway works, what are the constraints in the tunnels."

A subway tunnel is full of grease and grime - and, often, rats. "That's something we've talked about," Dr. Fortune said. "We've actually put Vectran samples in tunnels, to see if rats ate it. They didn't."

There are also obstructions like tracks, as well as an electrified third rail, pipes and safety walkways, all of which could cause gaps between the plug and the tunnel walls. Most of the obstructions can be dealt with by modifying a short section of the tunnel to accommodate the plug, which is nearly 10 meters long when inflated.

While a plug at either end of an underwater tube would protect against a tunnel breach, Hurricane Sandy showed that flooding can occur in many other ways - through ventilation grates and station entrances, for example.

Dr. Barbero's initial idea was to put plugs on rail cars so that they could be sent to any location, as needed. "That sounded really far-fetched" to Homeland Security officials, he recalled.

He came up with a more permanent installation: the plug sits, folded up, inside a long container snug against a tunnel wall, out of the way of passing trains.

On a signal, the container opens like a parachute bag, and the plug unfolds and inflates.

As with a parachute, proper folding is critical. "If you fold it wrong, it won't come out right," Dr. Barbero said.

"This is something like the air bag in your car," he added. "You depend on it. You don't think about it. You never use it, probably. But if you need it, it's got to be there, and it better work."

The New York Times

(China Daily 12/02/2012 page11)