Authentically Spanish cuisine

Updated: 2012-09-23 08:01

By Glenn Collins(The New York Times)

|

|||||||

|

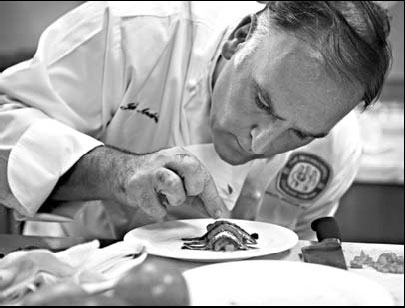

Jose Andres, the best-known Spanish chef working in the United States, prepares tomato seeds, diced tomato and Spanish anchovies. Richard Perry / The New York Times |

It seems an impossible dream, if not the one that the Man of La Mancha sang about onstage. But here it goes: over the next decade, dozens of American cooks schooled in the authentic cooking of Spain and trained in Spanish restaurants will begin to populate the United States. In due time, hundreds, then thousands, will serve up a cuisine that is not Mexican, or Caribbean, or Latin American, but one faithful to Spain.

Not only will they staff a national roster of credibly Spanish restaurants, but they will also go on to create new ones. Ultimately, that will increase American demand for the wine and products of Spain.

To that end, the dreamer himself - not Don Quixote, but Jose Andres, the best-known Spanish chef working in America - was cooking an egg in a culinary-school kitchen. He tipped a heated pan of olive oil and swirled the white as it coalesced around a gleaming yellow yolk.

It echoed a classic Diego Velazquez painting from the early 17th century, "Old Woman Cooking Eggs."

"It is Velazquez, it could not be more Spanish, and it is simple," said Mr. Andres, who has become the dean of Spanish studies at the International Culinary Center in Manhattan. "Everyone thinks that Spanish technique is complicated, but it is really about simplicity, and that is exactly what we must teach."

It was his passion for the cuisine of his homeland that led Mr. Andres to suggest that the culinary center create a program that immerses future professionals in the cooking and language of Spain.

One of the course's goals, to bring Spanish products more into the American mainstream, has never been more necessary. For even though Spain's reputation for gastro chic continues to swell, thanks to the renown of Ferran Adria and other chefs of the cocina de vanguardia, as the new Spanish cuisine is called, European austerity measures have brought on a culinary crisis in Spain.

The unemployment rate there is 24 percent, the highest in Europe, and about 12,000 restaurants have gone out of business since 2008.

To Mr. Andres, the new curriculum is nothing less than a show of faith in the future of Spanish cooking.

"It may be thought of as fashionable now," he said, "but it's not some fad. It is here to stay."

Mr. Andres, who is 43 and owns 14 restaurants in Las Vegas, Los Angeles, Miami and Washington, has long wanted to foster a Spanish cooking school. Last year he approached the culinary center's founder and chief executive, Dorothy Cann Hamilton, whom he has known since the 1990s. "He told me, 'We have to do a Spanish school,'" Ms. Hamilton recalled.

Much of the Spanish food in the United States has long been inauthentic, "a melange of many cultures - Mexican, Dominican, Puerto Rican and Portuguese," said Colman Andrews, a founder of Saveur magazine. Mr. Andrews, the biographer of Mr. Adria, is also the author of the Spanish cooking canon "Catalan Cuisine," published in 1988, and the editorial director of the food Web site The Daily Meal. "This curriculum takes Spanish cuisine back to its roots."

Mr. Andrews said that vast waves of French, Italian and Latin American immigrants over two centuries had given primary attention to their cuisines. Spanish food in the United States was so underrepresented, he said, that many Spanish people in the United States opened Italian restaurants.

In February, an initial class of 24 students will study for 10 weeks at the culinary center. The school expects the Spanish program to cost $5 million to open, including $1 million to develop the curriculum.

Mr. Andres recently visited a school kitchen to hold forth on his aesthetic, and his technique, with Candy Argondizza, a culinary center vice president who will oversee the teachers. "Trying to capture Jose's passion as a teacher - that will make our program work," she said.

As an example of the radical simplicity of Spanish cooking, Mr. Andres made the egg a la Velazquez, then mentioned that war horse, gazpacho, "which, if done correctly, is like no other soup in the world," he said. "Hard-core gazpacho is, conceptually, a liquid salad."

He hopes students will share his urgency to "nail down the basics of Spanish cooking before it gets too out of hand," he said, bemoaning the growing vogue for fusion. "I love Mexican food and South American food, and I have those restaurants. But you don't want Spanish cuisine to be bastardized."

Students will be immersed in everything from allioli (the paste made from garlic, olive oil and salt, without the eggs used in the Provencal aioli) to sofritto (long-cooked onions) and romesco (tomato-nut sauce).

Mr. Andres hopes that students will be given a deep understanding of the Spanish products underpinning the nation's cuisine, including pimenton, Iberico ham, dried seafood, cured tuna belly and the delicacy mojama (dried tuna packed in sea salt and hung in the sun to dry).

His vision is multigenerational. "If eventually we create a pool of thousands of people graduating from the program, this opens the possibility of thousands of new American restaurants putting out more authentic cooking," Mr. Andres said. "Now is the moment to push for the next level of quality in Spanish cuisine."

The New York Times

(China Daily 09/23/2012 page12)