A developer vs. India's gods

Updated: 2012-09-02 07:56

By Vikas Bajaj(The New York Times)

|

|||||||

|

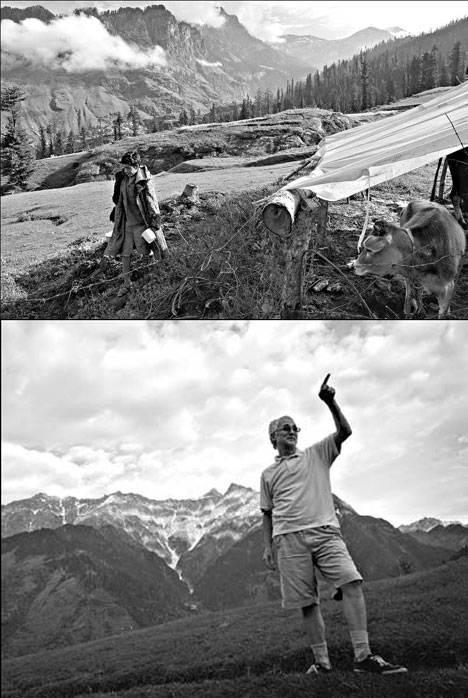

John Sims, an American hotel developer, wants to build a ski resort in Manali, India. A farm on the property, top. Photographs by Kuni Takahashi for The New York Times |

MANALI, India - To John Sims, the Himalayas, with some of the finest mountain slopes in the world, seemed like the perfect place to build India's first Western-style ski resort. But the local gods - or at least the holy men who claimed to speak for them - were his first challenge.

In the seven years since, Mr. Sims, an American hotel developer with years of experience working in India, has encountered seemingly endless setbacks.

Some opponents claimed falsely that the 46-hectare project would take over the entire valley. Others complained that the developers had underpaid landowners for their property. The state of Himachal Pradesh, which had once championed the $500 million proposal, moved to cancel it after a different political party took over. Now, a court has allowed it to go forward but has given the developers just six months to secure environmental permits from a government that has repeatedly stalled the project.

"My fundamental complaint is only this: Why did you invite us?" Mr. Sims said. "Why did you take our deposit? Why did you encourage us to spend money and then make a 180-degree turn?"

It is not easy to do business in India. The World Bank ranks India 166th out of 183 economies in the ease of starting a business.

Foreign direct investment was strong last year. But in the first six months of this year, it fell to $16.5 billion, down 18 percent compared with the same period in 2011, according to the Reserve Bank of India.

Some multinational companies have lost patience. Etisalat, a telecom company based in the United Arab Emirates; Eni, the Italian energy giant; and Fraport, a German airport developer, are either withdrawing from India or are said to be considering such a move because of delays and erratic policy changes.

"For foreign investors, a stable and predictable policy environment, along with dependable legal and political institutions, are key considerations in addition to market size and growth potential," said Eswar S. Prasad, an economist at Cornell University in Ithaca, New York. "Policy reversals and domestic power plays that turn foreign-financed projects into political footballs are likely to further dampen confidence among foreign investors."

India's economy is slowing sharply and becoming even more reliant on foreign capital. Prime Minister Manmohan Singh has become concerned enough to pledge friendlier policies.

About a decade ago, Mr. Sims, now 60, set his sights on building a ski resort like Vail in Colorado or Davos in Switzerland.

The resort investors found a seemingly ideal site. Though nobody lives on the spot year-round, villagers grow kidney beans and potatoes and graze their cows there. From three sides, there is a breathtaking view of the Kullu Valley, and the fourth side backs up to a mountain on which Mr. Sims planned to build a ski lift that would climb to 4,270 meters. "It's just about as spectacular as you can get," he said.

The location is a 10-hour drive from the nearest major airport, but Mr. Sims was optimistic about creating a winter wonderland. After a gondola ride up to the car-free village, visitors would find luxury hotels, a crafts bazaar, an ice rink and the ski lift.

Himachal Pradesh agreed to lease Mr. Sims forest land and to exempt him from a land ownership restriction.

The Ski Village would create 4,000 jobs, Mr. Sims said. Many local residents supported the project.

But others said lewd, loud Westerners would defile the area, known as "the valley of the gods" because many Hindu deities are said to reside here.

One landowner, Geeta Devi Katoch, said many people were angry when they learned that the developers had quietly bought some early parcels of land for one-third the price that prevailed once people learned of the project. She said her family, which grazes cows on the hilltop, would not sell. "This land is all we have," she said. "What will we do if we sell?"

In June, the Himachal Pradesh High Court gave Mr. Sims six months to obtain environmental approvals.

Mr. Sims said he felt that the odds were stacked against outsiders. "It's the robber baron era," he said, adding, "Only those strong Indian businessmen who know how to play the game can succeed."

Neha Thirani contributed reporting from Mumbai.

The New York Times

(China Daily 09/02/2012 page10)