Man's intrusion in nature spurs epidemics

Updated: 2012-07-22 06:48

By Jim Robbins(The New York Times)

|

|||||||

The term "ecosystem services" refers to the many ways nature supports the human endeavor. Forests filter the water we drink, for example, and birds and bees pollinate crops.

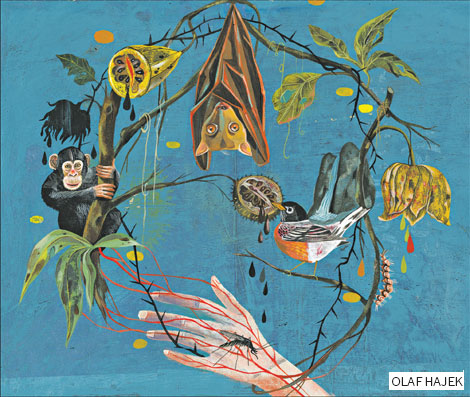

If we fail to understand and take care of the natural world, it can cause a breakdown of these systems and affect us in ways we know little about. An example is a developing model of infectious disease that shows that most epidemics - AIDS, Ebola, West Nile, SARS and hundreds more that have occurred over the last several decades - are a result of things people do to nature.

Disease, it turns out, is an environmental issue. Sixty percent of emerging infectious diseases that affect humans originate in animals - more than two-thirds in wildlife.

A global effort involving veterinarians, biologists, physicians and epidemiologists is trying to understand the "ecology of disease." It is part of a project called Predict, financed by the United States Agency for International Development. Experts are trying to learn, based on how people alter the land - with a new farm or road, for example - where the next diseases are likely to spill over into humans and how to spot them when they emerge, before they spread. They are gathering blood, saliva and other samples from high-risk wildlife species to create a library of viruses so that if one does infect humans, it can be more quickly identified. And they are studying ways of managing forests, wildlife and livestock to prevent diseases from leaving the woods and becoming the next pandemic.

It isn't only a public health issue, but an economic one. The World Bank has estimated that a severe influenza pandemic, for example, could cost the world economy $3 trillion.

The problem is exacerbated by how livestock are kept in poor countries, which can magnify diseases borne by wild animals. A recent study by the International Livestock Research Institute found that over two million people a year are killed by diseases that spread to humans from wild and domestic animals.

The Nipah virus in South Asia and the closely related Hendra virus in Australia are the most urgent examples of how disrupting an ecosystem can cause disease. The viruses originated with flying foxes, also known as fruit bats. They are messy eaters. They often hang upside down and eat fruit by masticating the pulp and then spitting out the juices and seeds.

Because the bats have co-evolved with the virus, they experience few effects from it. But once it breaks out of the bats and into species that haven't evolved with it, an epidemic can occur, as one did in 1999 in rural Malaysia. It is likely that a bat dropped a piece of chewed fruit into a piggery in a forest. The pigs became infected, and the virus jumped to humans, infecting 276. Many suffered permanent and crippling neurological disorders, and 106 died. There is no cure or vaccine. Since then there have been 12 smaller outbreaks in South Asia.

In Australia, where four people and dozens of horses have died of Hendra, suburbanization lured infected bats that were once forest-dwellers into backyards and pastures. If these viruses evolve to be transmitted readily through casual contact, the concern is that they could spread throughout Asia or the world.

"It's a matter of time that the right strain will come along and efficiently spread among people," says Jonathan Epstein, a veterinarian with EcoHealth Alliance, a New York-based organization that studies the ecological causes of disease.

"Any emerging disease in the last 30 or 40 years has come about as a result of encroachment into wild lands and changes in demography," says Peter Daszak, a disease ecologist and the president of EcoHealth.

Emerging infectious diseases are either new types of pathogens or old ones that have mutated, as the flu does every year. AIDS crossed into humans from chimpanzees in the 1920s when bush-meat hunters in Africa killed and butchered them.

Diseases have always come out of the woods and wildlife and found their way into human populations - the plague and malaria are two examples. But emerging diseases have quadrupled in the last half-century, experts say, largely because of human encroachment, especially in disease "hot spots," mostly in tropical regions. And air travel and a robust market in wildlife trafficking add to the potential for a serious outbreak in large population centers.

The key to preventing the next pandemic, experts say, is understanding what they call the "protective effects" of nature intact. In the Amazon, one study showed that an increase in deforestation by 4 percent increased the incidence of malaria by nearly 50 percent, because mosquitoes, which transmit the disease, thrive in recently deforested areas.

Public health experts have begun to factor ecology into their models. Australia just announced a multimillion-dollar effort to understand the ecology of the Hendra virus and bats.

It's not just the invasion of intact tropical landscapes that cause disease. The West Nile virus came to the United States from Africa but spread in America because one of its favored hosts is the American robin, which thrives in lawns and agricultural fields. And mosquitoes, which spread the disease, find robins especially appealing.

Lyme disease is also a product of human changes. Development chased off predators - wolves, foxes, owls and hawks. That has resulted in a fivefold increase in white-footed mice, which are great "reservoirs" for the Lyme bacteria.

"When we do things in an ecosystem that erode biodiversity - we chop forests into bits or replace habitat with agricultural fields - we tend to get rid of species that serve a protective role," says Richard Ostfeld, a Lyme disease researcher.

The best way to prevent an outbreak in humans, experts say, is with the One Health Initiative - a global program that advances the idea that human, animal and ecological health are inextricably linked and need to be managed holistically.

"It's not about keeping pristine forest pristine and free of people," says Simon Anthony, a molecular virologist at EcoHealth. "If you can get a handle on what it is that drives the emergence of a disease, then you can learn to modify environments sustainably."

The problem is huge and complex. Just an estimated 1 percent of wildlife viruses are known. Another major factor is the immunology of wildlife, an emerging science.

The fate of the next pandemic may be riding on the work of Predict. EcoHealth and its partners - the University of California at Davis, the Wildlife Conservation Society in New York, the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C., and Global Viral Forecasting, based in San Francisco - are looking at wildlife-borne viruses in the tropics, building a virus library.

Most critically, Predict researchers are watching the interface where deadly viruses are known to exist and where people are breaking open the forest, as they are along the new highway from the Atlantic to the Pacific across the Andes in Brazil and Peru. The effort might mean talking to people about how they butcher and eat bush meat or to those who are building a feed lot in bat habitat.

EcoHealth also scans luggage and packages at airports, looking for imported wildlife likely to be carrying deadly viruses. And its program called PetWatch warns consumers about exotic pets from forest hot spots.

"For the first time," said Dr. Epstein, "there is a coordinated effort in 20 countries to develop an early warning system for emerging zoonotic outbreaks."

The New York Times

(China Daily 07/22/2012 page11)