Suits deter art authentication

Updated: 2012-07-01 08:46

By Patricia Cohen(The New York Times)

|

|||||||

Art's celebrated freedom of expression may no longer extend to expert opinions on authenticity.

As spectacular sums flow through the art market and an expert verdict can make or destroy a fortune, several high-profile legal cases have pushed scholars to censor themselves for fear of becoming entangled in lawsuits.

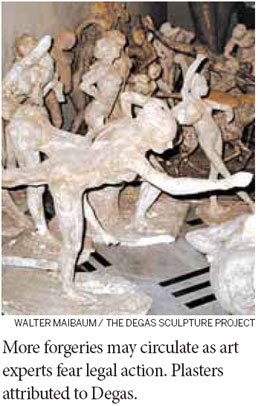

The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, the Roy Lichtenstein Foundation and the Noguchi Museum, all in New York, have stopped authenticating works to avoid litigation. In January the Courtauld Institute of Art in London cited "the possibility of legal action" when it canceled a forum on a controversial set of some 600 drawings attributed to Francis Bacon. And the leading experts on Degas have avoided saying if 74 plasters attributed to him are a stupendous new find or a hoax.

The anxiety has even touched the catalogue raisonne, the definitive, scholarly compendium of an artist's work. Auction houses sometimes refuse to handle unlisted works. As a result catalogue raisonne authors have been the targets of lawsuits, not to mention bribes and even death threats.

But the staggering rise in art prices has transformed the cost-benefit analysis of suing at the same time fraud has become more profitable, said Nancy Mowll Mathews, president of the Catalogue Raisonne Scholars Association.

Some warn the growing reluctance to speak publicly about authenticity could keep forgeries and misattributed works in circulation while newly discovered works go unrecognized.

In 2005, after watching other organizations fend off lawsuits, the Lichtenstein foundation bought $5 million worth of liability insurance and made its authentication process more rigorous and transparent, its executive director, Jack Cowart, said. Then in 2011 the Warhol foundation revealed it had spent $7 million defending itself against a lawsuit involving a silk-screen it had rejected for the catalogue raisonne. When Mr. Cowart called his insurance company to find out if the Lichtenstein foundation would be protected if faced with a similar suit, the agent said it was impossible to predict. "That was a very sobering moment," Mr. Cowart said.

Board members said the benefits of authenticating did not outweigh the risk of being sued. "Why should we go stand in front of a speeding car?" Mr. Cowart said. "It's not the role of the Roy Lichtenstein Foundation" to authenticate art.

That view disturbs Jack Flam, president of the Dedalus Foundation, based in New York, which is publishing Robert Motherwell's catalogue raisonne and was sued last year for changing its opinion about a painting's authenticity. "If experts stop speaking up, you're going to get more fakes surfacing," he said.

Sharon Flescher, executive director of the International Foundation for Art Research, said she doubts the number of lawsuits challenging expert opinions has gone up, but conceded that the perception is having "a chilling effect." Though few plaintiffs win, experts are deterred by the time and legal expense. That's why the College Art Association recently began offering affordable liability insurance to its members who authenticate art, she noted.

Peter R. Stern, an art lawyer in New York, tells clients never to volunteer an opinion unless formally asked by the owners, and even then to make sure the owners sign a waiver promising not to sue. "Art scholarship is fighting a losing battle against commerce," he said.

Fears of being sued may lead to changes in the nature of catalogues raisonnes, Ms. Flescher said. She pointed to recent decisions by the Calder and Lichtenstein foundations and the Noguchi Museum to move their catalog efforts online and label them "works in progress."Shaina D. Larrivee, manager of the Isamu Noguchi catalogue raisonne, said, "What we are presenting is a combination of completed research and research pending." She added, "We are very clear that 'research pending' does not guarantee inclusion in the final catalogue raisonne, and that we have the ability to remove artworks if new information comes to light."

Alexander Rower, Alexander Calder's grandson and chairman of the Calder Foundation, decided to forgo a catalogue raisonne in favor of an online guide to Calder, scheduled to go up soon. "You determine if your work is fake or not with the data we present," he said.

The New York-based foundation does not authenticate, he said, but it will register and examine a supposed Calder at an owner's request. And the foundation keeps a watchful eye on the market. Mr. Rower traveled to the Basel art fair in Switzerland in June to photograph every Calder for further research, he said.

And if he were to find a forgery?

"You can't just go out there in the world and say 'That's fake,'" Mr. Rower said. "But it is a fair thing for me to say to an art dealer, 'Have your presented this work to the Calder Foundation?' And if he says no, I say, 'You really should.'"

The New York Times

(China Daily 07/01/2012 page22)