A tree of life connects species

Updated: 2012-06-17 07:46

By Carl Zimmer(

The New York Times

)

|

|||||||

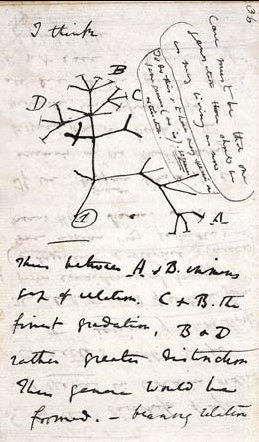

In 1837, Charles Darwin opened a notebook and drew a simple tree. Each branch represented a species. In that doodle, he captured his newfound realization that species were related, having evolved from a common ancestor. Across the top of the page he wrote, "I think."

Two decades later Darwin presented a detailed account of the tree of life in "On the Origin of Species." And much of evolutionary biology since then has been dedicated to illuminating parts of the tree. Using DNA, fossils and other clues, scientists have worked out the relationships of many groups of organisms, making rough sketches of the entire tree of life.

"Animals and fungi are in one part of the tree, and plants are far away in another part," said Laura A. Katz, an evolutionary biologist at Smith College in Northampton, Massachusetts.

|

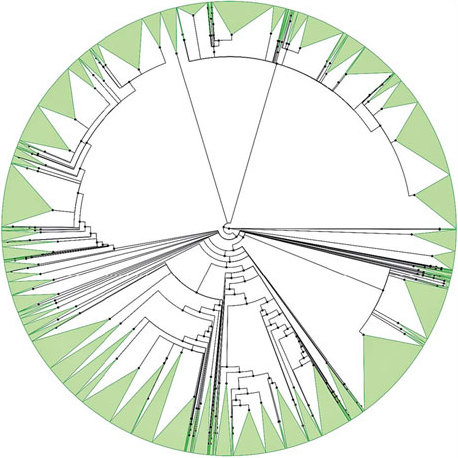

Scientists want to create a single tree of life out of thousands. An updated model, and Darwin's effort. Cambridge University Library; Iplant Collaborative, top |

Now Dr. Katz and her colleagues are doing something new: they are drawing a tree of life that includes every known species - a tree with about two million branches.

"I think it is an amazing step forward for our community if it can be pulled off," said Robert P. Guralnick, an expert on evolutionary trees at the University of Colorado who is not part of the project.

Until recently, a complete tree of life would have been inconceivable. To figure out how species are related, scientists inspect each possible way they could be related. With each additional species, the total number of possible trees explodes. There are more possible trees for just 25 species than there are stars.

But scientists have developed computer programs that find the most likely relationship among species without considering every possible arrangement. Those computers can now analyze tens of thousands of species at a time.

Yet these studies have thrown spotlights on only small portions of the tree of life.

"Nobody has tried to put all these results together," said the leader of the new effort, Karen Cranston, a biologist at the National Evolutionary Synthesis Center in Durham, North Carolina.

Last year, Dr. Cranston and other experts came up with a plan for a single tree of life. The National Science Foundation has awarded the team a three-year grant of $5.7 million. The project, the Open Tree of Life, hopes to publish a draft by August 2013. The scientists will grab tens of thousands of evolutionary trees archived online, then graft the smaller trees into a single big one.

These trees represent just a tiny fraction of all known species. The rest are classified in the old Linnaean system, in which they are assigned to a genus, a family, a kingdom, and so on. The team will use that data too. All the species in a genus, for example, will belong to branches descending from the same common ancestor. The Linnaean system will give the tree only a rough picture of the true relationships among species.

"Parts of it will be quite good, and parts will be quite bad," Dr. Cranston said.

The team will then set up an Internet portal where the entire community of evolutionary scientists can upload new studies, which can then automatically revise the entire tree.

And the tree will grow. Each year scientists publish descriptions of 17,000 new species. Last year a team estimated the total number of species to be 8.7 million, although others think it could easily be 10 times that.

When scientists publish the details of a new species, they typically compare it with known species to determine its closest relatives. They will be able to upload this new information into the Open Tree of Life. Scientists who extract DNA from the environment from previously unknown species will be able to add their information as well.

Animals and plants will take up only a tiny part of the tree. "Most biodiversity on earth is microbial," said Dr. Katz.

Microbes pose a special challenge. The branches of the tree of life represent how organisms pass their genes to their descendants. But microbes also transfer genes among one another. Those transfers can join branches separated by billions of years of evolution.

"In a lot of the tree of life, it's not really treelike," Dr. Cranston said.

She and her colleagues are exploring how they can build their database to include these gene transfers, and how best to visualize them.

"That's an issue we intend to struggle with for the next three years," Dr. Katz said.

Luke Harmon, an evolutionary biologist at the University of Idaho who is not involved in the project, looks forward to using the tree to explore the history of life. One major question evolutionary biologists have long explored is why evolution runs at different speeds in different lineages.

"We can use the tree to identify evolutionary 'bangs' and 'whimpers' through the history of life," said Dr. Harmon said. It may also be possible to see how climate change has driven extinctions, and to make predictions for the future.

Stephen A. Smith, a team member from the University of Michigan, hopes that the Open Tree of Life will allow scientists to tackle some major questions.

The tree may be able to guide the search for new drugs, for example. Scientists trying to treat infectious bacteria could search for the fungi that make antibiotics that are effective against it. The relatives of those fungi might make even more effective drugs.

"These are questions we can ask now," Dr. Smith said. "But we don't have all the data together to answer them yet."

Roderic D. M. Page, a professor of taxonomy at the University of Glasgow, called the Open Tree of Life team "first class," but added: "Displaying large trees is a hard problem that has so far resisted solution. We are still waiting for the equivalent of a Google Maps."

The New York Times

(China Daily 06/17/2012 page11)