Dam threatens a way of life

Updated: 2012-05-27 07:57

By Aaron Nelsen(The New York Times)

|

|||||||||

|

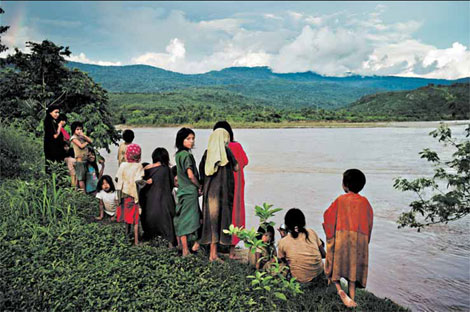

The Ashaninka people in Peru have faced encroachment from settlers and speculators, and now, a proposed hydroelectric dam. Tomas Munita for The New York Times |

In Peru, a project would flood a remote valley inhabited by indigenous people

Boca Sanibeni, Peru

Along the Ene River, in a remote jungle valley on the verdant eastern slopes of the Andes, the humming of an outboard motor draws the stares of Ashaninka children.

With encroachment from settlers and speculators, and after a devastating war against Shining Path rebels a decade ago, the indigenous Ashaninkas' hold is precarious. And they are now facing a new peril, the proposed 2,200-megawatt Pakitzapango hydroelectric dam, which would flood much of the Ene River valley.

The project is part of a proposal for as many as five dams that under a 2010 energy agreement would generate more than 6,500 megawatts, primarily for export to neighboring Brazil. The dams would displace thousands of people in the process.

Antonio Metzoquiari, 59, considered the implications for his community. "This is a grave matter," he said. "It's a return to violence, another war. I don't know where or how, but we would have to find a new place to live."

Hydroelectric dams have fallen out of favor in some parts of the world, but they remain attractive in much of Latin America, where a number of nations have plenty of water but lack other energy sources.

For now, the project is stalled in the Peruvian Congress. President Ollanta Humala has not staked out a clear position on the proposed dams, though that is likely to change when President Dilma Rousseff of Brazil visits Peru, a visit expected soon.

Despite claims that the welfare of affected communities is a top priority, several of the projects passed feasibility studies before local residents were even informed that the government had awarded concessions on the land. In response, the Central Ashaninka del Rio Ene, which represents Ashaninka populations, went to court to compel the Energy and Mining Ministry to disclose all feasibility studies.

After the project was announced, the organization brought together 17 Ashaninka communities to explain that a dam would inundate some communities and dry out others. Many people would be forced from their homes, critics argue, evoking memories of Peru's war against the Maoist-inspired Shining Path rebels, which officially ended in 2000 but scarred the Ashaninka.

Of the 70,000 people who were killed over two decades, 6,000 were Ashaninka, experts said. Thousands more were displaced.

The final speaker at the meeting, Dimer Dominguito, 25, who was accompanied by his wife and five children, captured the Ashaninka's outrage.

"In the city they make money and buy whatever they need, but here we live by our customs, our market, eating what we plant and we are happy," he said. "We want to defend our right to what is natural, to defend our market, and we support the government, but who supports us?"

The New York Times

(China Daily 05/27/2012 page9)