Protecting a species that most people fear

Updated: 2012-04-15 07:36

By Claudia Dreifus(The New York Times)

|

|||||||||

|

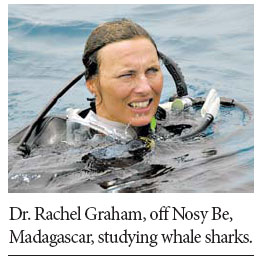

Snorkeling to tag, photograph and determine the sex of whale sharks. Photographs by Julie Larsen Maher |

BELIZE CITY, Belize - As the director of the Wildlife Conservation Society's Gulf and Caribbean Sharks and Rays Program, Dr. Rachel Graham must overcome deeply held fears and prejudices in her efforts to outlaw fishing of various shark species, including the whale shark, now protected off the coasts of Belize and Mexico. Last May Dr. Graham received the 2011 Gold Award and about $100,000 from the Whitley Fund for Nature in England for her work on its behalf.

An edited version of our conversations follows.

Q. What appeals to you about sharks?

A. They are beautiful and graceful. On an ecological level, they play an important role because they keep their prey species in check. You can see that there's great intelligence there. They haven't been around for almost 400 million years without having evolved tremendous smarts. One of the species I study - the whale shark - they are the most brilliant of navigators. They travel thousands of miles, and they arrive at a certain spot in Belize each year just when the reef fish are spawning and there's a wonderful buffet for them to eat.

Q. Give us a summary of the state of the world's sharks.

A. About 17 percent of 1,200 species of sharks and rays are threatened with extinction. For those species that swim in the open ocean, the numbers are even more dire. The International Union for the Conservation of Nature reports that a third of them are threatened. Most of their decline seems to be due to overfishing for shark fin soup - a prestige food in parts of Asia.

Q. Was it hard to win that ban on whale shark fishing in Belize?

A. People just adore whale sharks. They are huge and beautiful. It's much more difficult to protect other species because they are a large component of fisheries.

Q. What would you advise a traveler to China who is offered shark fin soup?

A. Think very carefully ... why you would want to eat species that are threatened with extinction and that are bad for you. The level of mercury is very high.

Q. What do you feel when you see headlines about shark attacks on swimmers?

A. It troubles me, of course. That sort of coverage is overblown, and it imperils many species. People ought to realize that when they go into the wilderness, they risk becoming part of the food chain.

Q. So is "Jaws" your least favorite movie?

A. In fact, it's not. It's got such great lines that as shark researchers we use again and again. Like, "We're going to need a bigger boat!" We love that line!

Q. Do you ever worry about being attacked?

A. I'm always sensitive to the moods of the sharks. The most serious threats I've encountered have come from people. There's a shadowy shark fishery here, operated by teams from Guatemala who work from isolated islands. The animals are killed at night and then shipped to landing sites in Guatemala where the meat and fins are exported. In 2007, I did a report for the Belizean government. I estimated how many sharks were being caught and taken out of the country. Afterward, I was told by a Guatemalan fisherman I'd worked with, "It's probably not a good time for you to go to Guatemala."

Q. Do you ever feel despair about what is happening to sharks?

A. Actually, I'm optimistic. I think there's a big chance for changing how people feel about sharks and rays. As people learn more about them, they see that their slaughter is unsustainable and morally wrong.

The New York Times

(China Daily 04/15/2012 page11)