The old ways gain favor for Koreans

Updated: 2012-02-19 08:36

By Choe Sang-Hun(The New York Times)

|

|||||||

|

Teaching South Korean children etiquette, including the tea ceremony, is a way to revitalize morality, some traditionalists believe. Photographs by Jean Chung for The International Herald Tribune |

YEONGJU, South Korea - When he looks out from the time-frozen world of Korea's oldest private Confucian academy, Park Seok-hong sees the rest of the country "turning into a realm of beasts." He points to recent news as evidence: young people swearing at elderly passengers in the subway and children jumping to their deaths to escape bullying or the pressure of hyper-competitive school life.

"We may have built our economy, but our morality is on the verge of collapse," Mr. Park said. "We must revitalize it, and this is where we can find an answer."

Mr. Park is chief curator of Sosu Seowon, a complex of 11 Confucian lecture halls and dormitories that first opened in 1543 in this town 160 kilometers southeast of Seoul.

In South Korea, where the word "Confucian" has long been synonymous with "old-fashioned," people like Mr. Park have recently gained with their campaign to reawaken interest in Confucian teachings that stress communal harmony, respect for seniority and loyalty to the state - principles that many older Koreans believe have lost their grip on the young.

In the past five years, a steadily increasing number of schoolchildren - as many as 15,000 a year - have come here for a course on Confucian etiquette.

Elsewhere, about 150 other seowon, or Confucian academies, have reopened for similar extracurricular programs, said Park Sung-jin, executive director of the National Association of Seowon in Korea.

"I came here so Grandpa will scold me less," explained Kang Ku-hyun, a sixth-grader from Seoul.

|

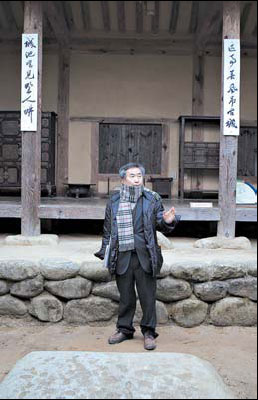

Park Seok-hong, the curator of a seowon school, argues that Confucianism has much to offer. |

For three days, the children sampled the life of Confucian students of old, receiving instruction on dinner and tea table etiquette and proper ways of addressing one's parents.

The seowon stay is part of a broader trend that emerged about a decade ago in the wake of the Asian financial crisis, when South Korea suffered economic setbacks and rising unemployment and suicide rates, and many people sensed a loss of the values that they believed had sustained older Koreans through hardships following the 1950-53 Korean War.

In recent months, South Korea has also been gripped by soul-searching after half a dozen students who had been bullied at school took their own lives. A series of suicides by soldiers has also shocked the country, which depends on a conscript military to guard against North Korea.

To address this unease, Buddhist temples have begun offering "temple stays," where city dwellers attempt meditation and poise. Marines run "survival camps," where schoolchildren crawl through obstacle courses in a regimen designed to instill comradeship and perseverance.

Centuries ago, carefully selected boys from across Korea lived secluded lives on this campus. In their heyday, more than 700 such academies dotted Korea, training applicants for the civil service and serving as guardians for the Confucianism that provided the ruling ideology of the Yi dynasty (1392-1897).

For decades, many Koreans strove to free themselves from the strictures of Confucian tradition, blaming it for things like the rigidly hierarchical corporate culture and a centuries-old preference for boys that once led to rampant abortions of female fetuses.

Still, champions of the seowon's importance argue that contemporary Korea can learn much from the old.

Mr. Park, the chief curator, has seized every opportunity to promote Confucian learning - to everyone from government officials to visiting tourists. "They accept one-tenth of what I say," he said. "They look at me as if I were crazy, ultraconservative, out of fashion. I feel like an outcast."

The New York Times

(China Daily 02/19/2012 page11)