Taking a stand to protect privacy

Updated: 2012-02-12 07:51

By Somini Sengupta(The New York Times)

|

|||||||||

Max Schrems, a 24-year-old law student from Salzburg, Austria, wanted to know what Facebook knew: He requested his own Facebook file. What he got turned out to be a virtual bildungsroman, 1,222 pages long. It contained wall posts he had deleted, old messages that revealed a friend's troubled state of mind, even information that he didn't enter himself about his physical whereabouts.

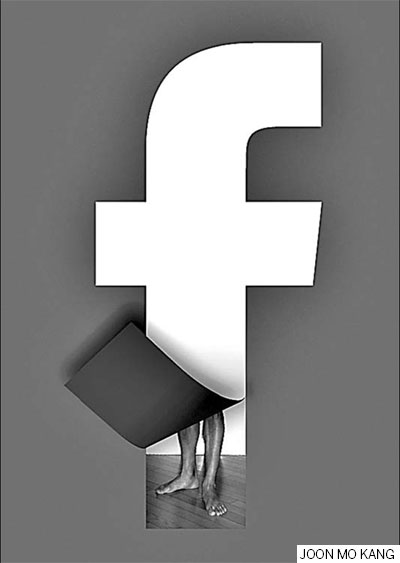

Mr. Schrems felt a vague disquiet about what Facebook could do with all that information. Why was it there at all, he wondered, when he had deleted it? "It's like a camera hanging over your bed while you're having sex. It just doesn't feel good," he said."We in Europe are oftentimes frightened of what might happen some day."

Mr. Schrems's sentiment is emblematic of the discomfort sweeping Europe about the ways in which Internet companies treat personal information. That discomfort has prompted proposals for stricter regulation of online data across the continent. And Europe's moves to protect Internet privacy have given rise to a thorny question: How do the laws and mores of nations manage, if at all, the multinational companies that now govern our digital lives?

Personal data is the oil that greases the Internet. Each one of us sits on our own vast reserves. The data that we share every day - names, addresses, pictures, even our precise locations as measured by the geo-location sensor embedded in Internet-enabled smartphones - helps companies target advertising based not only on demographics but also on the personal opinions and desires we post online. Those advertising revenues, in turn, make hundreds of millions of dollars for companies like Facebook.

The European media seized on Mr. Schrems's discovery. German newspapers published instructions on how to request personal files from Facebook. Within months, 40,000 people had made requests. The data protection office in Ireland, where Facebook has its European center, conducted an audit of Facebook's data retention practices; the company agreed to overhaul the way it collects data in Europe, including disposing of data "much sooner."

German regulators have scrutinized facial recognition technology. The Netherlands is considering a bill that would require Internet users to consent to being tracked as they travel from Web site to Web site. And last month, the European Commission unveiled a sweeping privacy law that would require companies to obtain explicit consent before using personal information, inform regulators and users in the event of a data breach and, most radical, empower Europeans to demand that his or her data be deleted forever.

"Europe has come to the conclusion that none of the companies can be trusted," said Simon Davies, the director of the London-based nonprofit Privacy International. "There is a growing mood of despondency about the privacy issue."

Every European country has a privacy law, as do Canada, Australia and many Latin American countries. The United States remains a holdout. It has laws that protect health records and financial information, and even one that keeps private what movies people rent. But there is no law that spells out the control and use of online data.

Social mores around privacy vary widely across the globe. In Japan, Google was criticized for being intrusive when its self-driven cars cruised the streets with a camera snapping pictures for Google Street View. In India, the notion of privacy seems foreign. A shopkeeper might casually ask a childless woman if she has gynecological trouble; school grades are posted on public walls; many people still live in extended families, literally wandering in and out of one another's bedrooms. But a project to issue biometric identity cards to every Indian recently set off a flurry of concern, prompting the government to draft a law that enshrines the right to privacy for the first time.

Part of the difficulty in regulating online privacy is the speed of technological innovation. Just as it becomes remarkably easy for us to share our information with others, it also becomes cheaper and easier to crunch and analyze that information - and store it forever.

Most people may not have much to hide. For a few, not sharing personal information may be vital.

They're the ones who need the protection of the law, argued Rebecca MacKinnon, a fellow at the New America Foundation and author of "Consent of the Networked," a book about digital freedom.

"It may be victims of domestic abuse who don't want to be stalked or tracked, or it could be dissidents in Syria, or someone who has weird opinions and could mistakenly end up on a watch list when they don't deserve it," said Ms. MacKinnon. "If you have a democratic society, the point is not to say whatever is good for the majority is all we need."

The New York Times

(China Daily 02/12/2012 page9)