Defending world's greatest sites

Updated: 2012-01-29 07:58

By Steven Erlanger(The New York Times)

|

|||||||

|

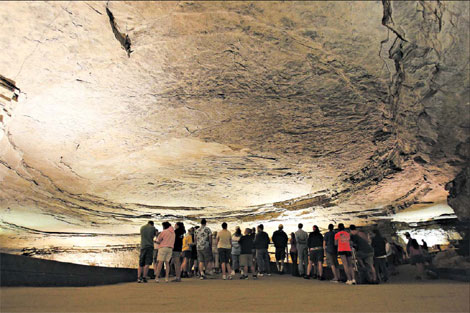

Tourists flock to World Heritage sites like Mammoth Cave National Park in Kentucky and, below, Jordan's Petra ruins and the Leaning Tower of Pisa in Italy. Ed Reinke / Associated Press |

World Heritage is big business, bringing hordes of tourists to poor countries. It can also overwhelm the very sites it is designed to protect, with chain hotels and restaurants and thousands of feet treading on fragile ground.

But World Heritage can also recognize traditions that might have little aesthetic value to any group but the one practicing it.

The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (Unesco) has created two treaties to enshrine the concept of heritage.

|

Erik De Castro / Reuters |

The World Heritage Convention, dating from 1972, was set up to defend a wild landscape before it disappeared. The Convention for the Safeguarding of Intangible Cultural Heritage was introduced in 2003 to defend traditions, and is more controversial. Some 188 nations have ratified the first convention. To date, there are 725 cultural, 183 natural and 28 properties combining the two, in 153 countries. The list includes the Leaning Tower of Pisa and Venice and its lagoon, in Italy. Jordan has Petra and Wadi Rum. France even lists the banks of the Seine.

Russia has the Kremlin, Red Square and Lake Baikal. The United States list includes Yellowstone National Park, the Grand Canyon and the Everglades. Luxembourg pretty much lists itself; Afghanistan includes the remains of the great Buddhas of Bamiyan, blown up by the Taliban.

The Marshall Islands has the Bikini Atoll Nuclear Test Site (preserving a place consecrated to the potential end of everything).

In his book "Disappearing World: The Earth's Most Extraordinary and Endangered Places," Alonzo C. Addison, a director in Unesco's external relations department, arranges sites in varying degrees of distress, from causes that include conflict, theft, development, pollution, invaders and tourism.

Conflict is the most obvious, whether in Afghanistan, Jerusalem, Kosovo or around the Preah Vihear temple on the border of Cambodia and Thailand, where there have been armed clashes.

The Darfur crisis has done extraordinary damage to the Garamba National Park in the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

But most troubling may be mass tourism. "The world is more global and some sites can't deal with all the tourists," Mr. Addision said, whether it's Machu Picchu or Angkor Wat. (Unesco is trying to put Machu Picchu on the list of endangered sites.)

"The dark side, of course, is consumption," said Francesco Bandarin, assistant director-general of Unesco and head of its World Heritage Center, speaking of the consumerism that often surrounds heritage sites.

"And consumption and preservation do not go together." If a site is "within an hour of a harbor," he added, "it becomes inundated by a flood of tourism and geysers of money."

Angkor, he said, now has 200 hotels nearby. "The tourism industry has a lot of power in many poor countries but a short-term vision," Mr. Bandarin said.

So far, 139 countries have signed the Cultural Heritage convention. Of the 267 traditions enshrined, 27 are "in need of urgent safeguarding," including "the watertight-bulkhead technology of Chinese junks." The regular list includes oral traditions and performances, social rituals and crafts - including Cambodia's Royal Ballet and Indonesian puppet theater. And the French gastronomic meal.

But inclusion on the list can lead to manipulation. The French gastronomic meal preserves the lavish family occasion that marks major life events.

So Unesco was not pleased that some 60 French chefs used the designation to promote themselves with a celebration at Versailles last April where meals largely prepared elsewhere were trucked in. There is talk of taking the recognition away.

Cecile Duvelle, the French anthropologist in charge of Unesco's intangible heritage section, fiercely defends the concept. The point, she said, is not to "preserve and protect, which is to freeze something, but to safeguard," as a sort of living heritage. Traditions can change as they are passed down, she noted, yet provide a sense of identity. In return for listing the traditions, governments commit to promote and support them, by, for example, stopping deforestation.

"The value," Ms. Duvelle said, "is for the community, not for the world."

The New York Times

|

Fabio Muzzi / Agence France-Presse - Getty Images |

(China Daily 01/29/2012 page11)