A dance pioneer, hailed and hated

Updated: 2012-01-15 08:09

(The New York Times)

|

|||||||

|

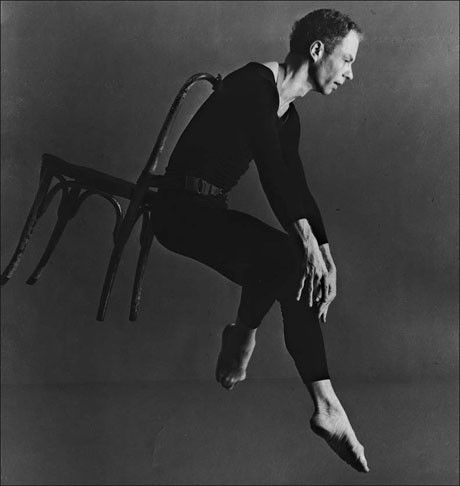

Merce Cunningham's bold choreography demanded much of both dancers and audiences Cunningham in a 1958 performance of "Antic Meet." Richard Rutledge / Merce Cunningham Dance Company |

Not long before his 80th birthday in 1999 the choreographer Merce Cunningham was asked by his brother: "When are you going to make something the public likes?"

A month later at Zellerbach Hall in Berkeley, California, Cunningham and his dancers received a huge ovation for the world premiere of his "Biped." This was to be the most sensational, abundant and internationally acclaimed work of his old age, a cornucopia that kept suggesting images of death and transcendence, with choreography partly devised on a computer. For the remaining 10 years of his life he was hailed as the world's greatest living choreographer.

Yet his pioneering company, founded in 1953, has kept confronting people with one challenge after another, even after his death in 2009. His company gave its last-ever performance on New Year's Eve. His works may be revived by other companies, but without specifically trained dancers, it is likely that much will be lost.

Problematic to appreciate, taxing to execute, Cunningham choreography did not grow more palatable, even as his technique became taught around the world. During a 2005 performance in London of his "Ocean" (1994), a piece danced in the round, people actually walked onto the stage in their urgent quest of the exit. Last year, at performances of his last work "Nearly Ninety2" (2009), some audience members were converted, but others fled.

What his dancers did was virtuosic and strange. The technique was about complex coordination and rhythm, and balance within off-balance situations.

His dancers were likened to robots. Sometimes they visibly worked with intense concentration. ("It's when dancing gets awkward that it starts to become interesting," Cunningham liked to say.)

They employed extremes of speed and slowness; they were frequently motionless (often on one leg). They tilted their backs to a rare extent.

Among the first 10 people passionate about his work were the artists Robert Rauschenberg and Jasper Johns, who both designed for the company. "Nothing Merce does is simple," Mr. Johns said in 1968. "Everything has a fascinating richness and multiplicity of direction."

The first and crucial challenge of Cunningham's dance theater was the way dance, music and design were presented as equal and independent forces, frequently colliding.

But the notorious difficulty surrounding Cunningham - for 50 years the partner of the composer John Cage - arose from the nature of the music he chose.

Some Cunningham scores were deafening. In some of his works dance and music shared the same peacefulness; but in others the alienation between music and dance was the point. When a dancer maintained calm equilibrium amid a soundscape like jet rockets or radiator clankings, the effect could prove grace under pressure. Or dancers doing slow falls against near-silence showed the drama of pure movement in isolation.

In "Shards" (1987), a bleak but startling work, I remember dancers frozen for long periods, leaning from the waist at extraordinary angles, and then short outbreaks of spasmic movements. A grim work - so why is it so haunting? At the time Cunningham said: "Society is split into so many directions. Look at the disintegration. So many things are falling apart, so many people are having troubles of various kinds. There is no center. I think that the center lies in oneself. Each person has to find it for himself. I think 'Shards' must come from all that kind of thinking."

Yet "Shards" went deeper than social conditions; nature itself seemed afflicted by a nervous breakdown. This was poetic drama of a profound order. It changed my mental landscape.

The defining image of American modern dance, from Isadora Duncan to Martha Graham, had been of the individual heroically confronting space. But with Cunningham the drama of isolation in space acquired many more facets (privacy, meditation, alienation).

No choreographer was ever more devoted to new possibilities. Cunningham often started a piece with definite ideas (his notes for one work included Aristotle, Falstaff, and Laurel and Hardy), but then used chance methods (and the computer) to shape his treatment.

Now this incomparably imaginative enterprise is ending. This was Cunningham's own decision. His career was devoted to the new; his company was not to dwindle into a museum.

The difficulty of this dance theater was intimately connected to its greatest rewards. Rhythm, line, balance, phrasing, drama, expression and aesthetics were all constantly redefined. We had to chase to keep up. Along the way our lives were repeatedly changed.

The New York Times

(China Daily 01/15/2012 page12)