Testaments of history

Updated: 2011-11-13 07:02

By Zhang Kun(China Daily)

|

|||||||||

|

The size, technique and inscriptions make the Dake Ding unique and a national treasure. Provided to China Daily |

Three ceremonial bronze tripods each command pride of place in separate museums in China. Zhang Kun pays respect to one of them.

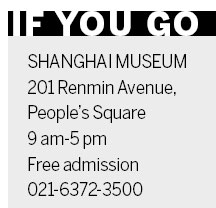

If there is only time to see one piece of history in Shanghai, then you must go to the Shanghai Museum and search out a bronze tripod in its bronze collection. This is a 2,000-year-old bronze tripod that dates from the Western Zhou Dynasty (c. 11th century-771 BC). They call it the Dake Tripod, or Dake Ding (大克鼎).

Its brother cauldron, the Dayu Tripod or Dayu Ding (大孟鼎), was loaned to Beijing, at the end of the 1950s, to join the then newly launched National Museum of History. It is now part of the collection of the National Museum.

Another famous tripod is the Maoging Ding (毛公鼎), which is the centerpiece of the Taipei Palace Museum, having left the mainland together with the Kuomintang forces in 1948.

These bronze cauldrons were used for ceremonial rituals in the Zhou Dynasty and they are precious records of the language and culture of those faraway times.

In Shanghai, the Dake Tripod also provided the impetus for the museum's bronze collection, which is one of the best in the country and the world.

"Several generations worked for decades to put together the collection," says Zhou Ya, director of the bronze department at Shanghai Museum. "We have a large and systematic collection, with items typical of each important period to form a linear history. More importantly, we have some very precious, state-level treasure pieces."

Since its founding in 1952, the Shanghai Museum has pushed to add to its bronzes, with some important pieces collected and rescued from foundries.

"We used to send archaeologists to these smelters, picking up antiques from the piles of recycled scrap metals," Zhou says. "Later, we trained some workers at the foundries so they could put aside anything that looked like an antique."

Thousands of valuable pieces were collected this way, including many top-grade antiques. But the discoveries have petered out now because the foundries no longer melt down recycled scraps.

But the Dake and Dayu tripods had a different story.

The Dake Ding stands 93.1 centimeters tall, has a diameter of 75.6 centimeters, and weighs more than 200 kilograms. It was unearthed in a village in the Famensi region, in Shaanxi province in the 19th century. Its size, technique and inscriptions make the Dake Ding unique and a rare national treasure.

Two hundred and ninety characters are inscribed on the cauldron, documenting the occasion of a high-ranking official named Ke who received largess from the King of Zhou.

"For the researchers, it provided important evidence of the economic system of the Western Zhou period," Zhou says.

The Dake and Dayu tripods were donated to the Shanghai municipality in 1951 by Pan Dayu (潘达于), who believed "important antiques can only realize their value in a public museum". They were just two of the more than 200 pieces donated by the family.

Pan Zuyin (潘祖荫) (1830-1890), was a high-ranking official, scholar and dedicated collector of antiques. His collection was kept safe by his family in Suzhou, Jiangsu province and it was variously guarded from foreign buyers and invaders.

In 1937, Japanese planes bombed Suzhou and the Pan family decided to seek shelter some place else. Before they left, they buried the two bronze cauldrons, since they were too heavy to evacuate.

A hole was dug under the floor of the living room, and the bronzes were buried and covered over by a brick floor. Although the Japanese repeatedly raided the Pan house for the famous collection, it was never found.

An American once offered to pay 300,000 kilogram of gold for it and even added a villa to the bargain, but Pan Dayu, the mistress of the household, turned him down. She was Pan Zuyin's granddaughter-in-law.

After she donated the cauldrons to Shanghai, Pan Dayu received a citation from the Ministry of Culture, and it hung on her bedroom wall for 50 years. She died in Suzhou in 2007.

After the Dayu Ding went to Beijing, Dake Ding became the most prominent exhibit in the bronze hall of the Shanghai Museum.

The collection occupies the largest hall on the ground floor and more than 400 items are displayed in the permanent exhibition. Although the museum sometimes loans exhibits to museums abroad, a national treasure like the Dake Ding is not allowed out of China.

You can contact the writer at zhangkun@chinadaily.com.cn.

(China Daily 11/13/2011 page15)