Planet's green guardians, under siege

Updated: 2011-10-09 07:56

By Justin Gillis(The New York Times)

|

|||||||

|

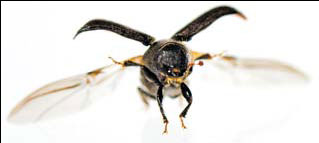

The mountain pine beetle, top right, is damaging evergreen forests that are also threatened by wildfires. Both scourges ravaged a forest in Montana, and might be worsened by a changing climate. Photographs by Josh Haner / The New York Times |

Trees slow the warming trend, but they feel its effects

Wise River, Montana

The trees spanning many of the mountain sides of western Montana glow an earthy red, like a broadleaf forest at the beginning of autumn.

But these trees are not supposed to turn red. They are evergreens, falling victim to beetles that used to be controlled in part by bitterly cold winters. As the climate warms, scientists say, that control is no longer happening.

Along with such insect infestations, forests throughout the world are contending with droughts, wildfires and other perils that may also be related to climate change.

Experts are scrambling to understand the situation, and to predict how serious it may become. They say the future habitability of the Earth may depend on the answer.

Precise numbers deduced only recently show that forests have slowed global warming by absorbing more than a quarter of the carbon dioxide that people are putting into the air. Trees are effectively absorbing the emissions from all the world's cars and trucks.

Without that disposal service, the level of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere would be rising faster. The gas traps heat from the sun, and human emissions are causing the planet to warm. But some scientists are worried that as the warming accelerates, trees themselves could become victims on a massive scale of the various effects of climate change.

"At the same time that we're recognizing the potential great value of trees and forests in helping us deal with the excess carbon we're generating, we're starting to lose forests," said Thomas W. Swetnam, an expert on forest history at the University of Arizona.

If enough trees were to die, forests would not only stop absorbing carbon dioxide, they might also start to burn up or decay at such a rate that they would spew huge amounts of the gas back into the air. That, in turn, could speed the warming of the planet, unlocking yet more carbon stored in once-cold places like the Arctic. Scientists are not sure how likely this feedback loop is, and they are not eager to find out the hard way.

It is clear that the point of no return has not been reached yet " and it may never be. Despite the troubles of recent years, forests continue to take up a large amount of carbon.

"I think we have a situation where both the 'forces of growth' and the 'forces of death' are strengthening, and have been for some time," said Oliver L. Phillips, a prominent tropical forest researcher with the University of Leeds in England. "The latter are more eye-catching, but the former have in fact been more important so far."

Scientists acknowledge that their attempts to use computers to project the future of forests are still crude. Some of those forecasts warn that climate change could cause widespread forest death in places like the Amazon, while others show forests remaining robust carbon sponges throughout the 21st century.

Many scientists say that ensuring the health of the world's forests requires slowing human emissions of greenhouse gases. Most nations committed to doing so in a global environmental treaty in 1992, yet two decades of negotiations have yielded scant progress.

In the near term, experts say, more modest steps could be taken to protect forests. One plan calls for wealthy countries to pay those in the tropics to halt the destruction of their immense forests for agriculture and logging.

But now even that plan is at risk, for lack of money. Other strategies, like thinning overgrown forests in the American West to make them more resistant to fire and insect damage, are also running short of money.

Many scientists had hoped that serious forest damage would not set in before the middle of the 21st century, and that people would have time to get emissions of heat-trapping gases under control. Some of them have been shocked in recent years by what they are seeing.

"The amount of area burning now in Siberia is just startling," Dr. Swetnam said. "The big fires that are occurring in the American Southwest are extraordinary in terms of their severity, on time scales of thousands of years. If we were to continue at this rate through the century, you're looking at the loss of at least half the forest landscape of the Southwest."

The carbon dioxide mystery

As best researchers can tell, the oceans take up about a quarter of the carbon emissions arising from human activities. Trees are taking up a similar amount of carbon.

While all types of plants absorb carbon dioxide, known as CO2, most of them return it to the atmosphere quickly because their vegetation decays, burns or is eaten. It is mainly trees that have the ability to lock carbon into long-term storage, and they do so by making wood or transferring carbon into the soil. The wood may stand for centuries inside a living tree, and it is slow to decay even when the tree dies.

But the carbon in wood is vulnerable to rapid release. If a forest burns down, for instance, much of the carbon stored in it will re-enter the atmosphere.

Destruction by fires and insects is a part of the natural history of forests, and in isolation, such events would be no cause for alarm. Indeed, despite the recent problems, a new estimate, published August 19 in the journal Science, suggests that when emissions from the destruction of forests are subtracted from the carbon they absorb, they are, on balance, packing more than 900 million metric tons of carbon into long-term storage every year.

One major reason is that forests, like other types of plants, appear to be responding to the rise of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere by growing more vigorously. The gas is, after all, the main food supply for plants. Scientists have been surprised in recent years to learn that this factor is causing a growth spurt even in mature forests, a finding that overturned decades of ecological dogma.

Climate-change contrarians tend to focus on this "fertilization effect," hailing it as a boon for forests and the food supply. They assert that this effect is likely to continue for the foreseeable future, ameliorating any negative impacts on plant growth from rising temperatures.

More mainstream scientists, while stating that CO2 fertilization is real, are much less certain about the long-term effects, saying that the heat and water stress associated with climate change seem to be making forests vulnerable to insect attack, fires and many other problems.

"Forests take a century to grow to maturity," said Werner A. Kurz, a Canadian scientist who is a leading expert on forest carbon. "It takes only a single extreme climate event, a single attack by insects, to interrupt that hundred-year uptake of carbon."

It is possible the recent die-backs will prove transitory, but some are doubtful.

"If this were happening in just a few places, it would be easier to deny and write off," said David A. Cleaves, senior adviser for the United States Forest Service. "But it's not. It's happening all over the place. "

In some places, higher temperatures could aid tree growth or cause forests to expand into zones previously occupied by grasslands or tundra, storing more carbon.

Forests are re-growing on abandoned agricultural land across vast reaches of Europe and Russia. China, trying to slow the advance of a desert, has planted nearly 40 million hectares of trees.

But the planet simply does not have room for many more of forests. To expand them significantly would require taking more farmland out of production, an unlikely prospect.

Wildfires and bugs

The mountain pine beetle has pushed farther north into Canada than ever recorded. The beetles have jumped the Rocky Mountains into Alberta, and fears are rising that they could spread across the continent in coming decades.

In the American West, warmer temperatures are causing mountain snowpack to melt earlier. That is causing greater water deficits in the summer, just as heat cause trees to need extra water to survive. The landscape dries out, and the stressed trees become more vulnerable to both fire and beetles.

Arizona, New Mexico and Texas have been so dry that huge, explosive fires consumed millions of hectares this summer.

The role of climate change in causing the drought is unclear " the more immediate cause is an intermittent weather pattern called La Nina.

Bu experts say that climatic change may ensure that some areas burning this year will never return as forest - they are more likely to grow back as heat-tolerant grass.

"A lot of ecologists like me are starting to think all these agents, like insects and fires, are just the proximate cause, and the real culprit is water stress caused by climate change," said Robert L. Crabtree, head of a center studying the Yellowstone region in Montana. "It doesn't really matter what kills the trees - they're on their way out. The big question is, are they going to regrow? "

Stalled efforts

A scientific consensus has emerged that people mismanaged widespread areas of pine forest in the Western United States over the past century, in part by suppressing the mild ground fires that used to clear out underbrush and limit tree density.

As a consequence, these overgrown forests have become tinderboxes that can be destroyed by high-intensity fires. The government stance is that many forests throughout the West need to be thinned, and some environmental groups have come to agree.

But with little money available to subsidize the thinning, the United States Forest Service is reduced to treating only small sections of forest. On an even larger scale, experts cite a lack of money as endangering a program to slow or halt the destruction of tropical forests at human hands.

Rich countries agreed in principle in recent years to pay poorer countries large amounts of money if they would protect their forests. But climate legislation stalled in the United States amid opposition from lawmakers worried about the economic effects, and some European countries have also balked at sending money abroad. That means it is not clear the forest program will ever get rolling in a substantial way.

"Like any other scheme to improve the human condition, it's quite precarious because it is so grand in its ambitions," said William Boyd, a University of Colorado law professor working to salvage the plan.

The best hope for the program now is that California, which is intent on battling global warming, will allow industries to comply with its rules partly by financing efforts to slow tropical deforestation. The idea is that other states or countries would eventually follow suit.

Yet, scientists emphasize that in the end, programs meant to conserve forests - or to render them more fire-resistant, or to plant new ones - are only partial measures.

To ensure that forests are preserved for future generations, they say, society needs to limit the fossil-fuel burning that is altering the climate of the world.

The New York Times

|

Some of the world’s forests, as they decay, are starting to release more carbon than they take up. Measuring decay in Harvard Forest in Massachusetts. Josh Haner / The New York Times |

(China Daily 10/09/2011 page9)