Defining the mystical gift of charisma

Updated: 2011-08-28 08:01

(The New York Times)

|

|||||||

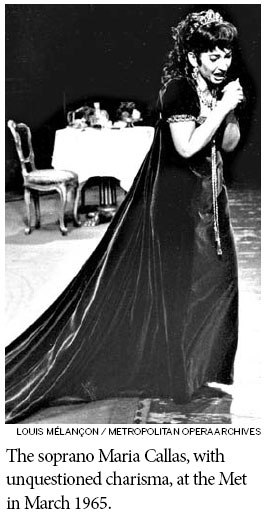

On March 19, 1965, Maria Callas returned to the Metropolitan Opera after a seven-year absence. It was one of the most anticipated nights in Met history.

The next day Harold Schonberg reported in The Times that Callas's first entrance set off a wave of applause for several minutes. There were 16 curtain calls at the end.

Charisma, critics like to call it. In recent reviews in The Times I've referred to "the charismatic Russian baritone Dmitri Hvorostovsky," "the charismatic Helene Grimaud" and "the quietly charismatic folk singer and songwriter Sam Amidon." Of a benefit concert for Japan I referred to a "dazzling variety of charismatic frontwomen."

But what is charisma?

Charismatic performers are those whom you simply can't look away from. Their charisma is an almost physical presence, a spark that powers even the most unassuming musical passage.

To experience a charismatic performance is to feel elevated, simultaneously dazed and focused, galvanized and enlarged. It is to surrender to something raw and elemental, to feel happy but also unsatisfied.

Charisma is demanding. We are told of Callas's overwhelming use of her body onstage.

It is a mystifying gift that cannot be taught. The young tenor Vittorio Grigolo is still getting used to singing onstage, but his charisma is unmistakable.

We now have a culture in which the technical ability of artists is far more impressive than ever. But charisma is not virtuosity. Christian Tetzlaff is a technically flawless violinist, but he isn't charismatic. Joshua Bell, less innovative if just as virtuosic, is.

There is remarkable unanimity to our recognition of charisma. Reviewing a recital featuring the countertenor David Daniels in The Times in April I wrote that "his charisma and softly velvet tone were no surprise"; in mid-August Anthony Tommasini reported in The Times from Santa Fe, New Mexico, that Mr. Daniels sang "with the expected virtuosity and charisma."

Last fall the soprano Marina Poplavskaya took the leading roles in two new Verdi productions at the Met. Her voice is more interesting than beautiful, and her breathing is a mess. But she has charisma.

In "Don Carlo," when Elisabetta learns her lady in waiting has betrayed her, she demands the return of a small cross. Ms. Poplavskaya held out her hand for the piece, and her presence made the moment shattering.

Charisma works most strongly on a visual level; it's telling that we say "You can't take your eyes off her." Audio recordings can be modified to create an illusion of command. Film never lies.

For the ancient Greeks charisma was, simply, favor. Charis, whose name meant beauty and kindness, was an attendant to Aphrodite, the goddess of love.

In Christian theology, gifts from God are "charismata."

To some, charisma has lost its power. It is a given, we imply, so let's move on to the real stuff.

Let's assume that charisma is the real stuff, less a means than an end in itself. What we consider the "content" of the arts - the notes, the plot - is actually just the structure that makes possible the crucial thing: the aria or sonata provides a platform for us to experience the charisma.

If charisma were recognized as the central experience of performance, that experience would take on a ritualistic aspect. Art would be less an appeal to our intelligence or taste than to instincts we barely acknowledge.

Charisma fits well in a culture in which the connoisseurship of artistic technique has declined, but institutions are still seeking new audiences. Even if you know little about the technicalities of music, when you attend a performance by the pianist Evgeny Kissin, you are swept up by his power and presence.

The question is whether people want to be swept up. Charisma can be frightening; it demands a trust not easily conceded. If our desire from performance is only for comfort and reassurance, charisma will repel us. Recently I heard the soprano Aprile Millo sing an aria on a CD with burning intensity. Later I e-mailed her to ask her what charisma is.

"Hemingway gave us a haunting clue to it," she replied. "In his obsession with the Spanish bullfights, he spoke of the lust of the crowd and its desire to feel something special, a raw authenticity, even in so brutal a setting. What he mentions is the hush that would come over the crowd at the entrance of the toreadors. The people could sense the difference between those who did it for the fame, the paycheck, and those who had the old spirit: the nobility, bravery, heart, 'duende.' I believe this also happens in the theater. The crowd can sense the one with the authentic message, the connection to the truth."

The New York Times

(China Daily 08/28/2011 page12)