Small fists hold tight in a lesson on rodeo

Updated: 2011-08-28 08:00

By Sarah Maslin Nir(The New York Times)

|

|||||||||

|

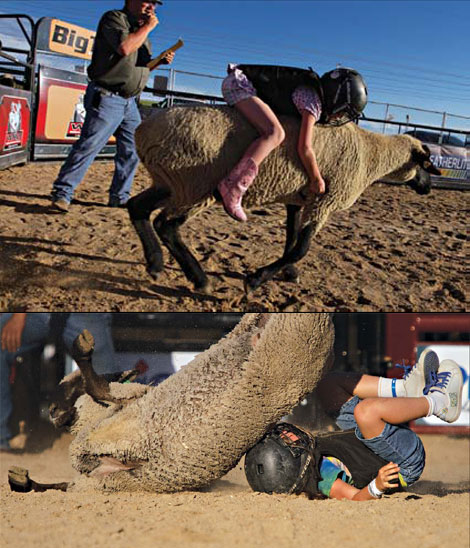

Mutton busting is gaining popularity among American children, like these at the Arapahoe County Fair in Colorado. Children wear protective helmets. Photographs by Rob Mattson for The New York Times |

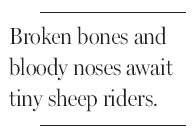

AURORA, Colorado - Kaden Bustamante tottered out of the rodeo arena after his brief, rough ride landed him face down in the dirt. He spit dust and tried to stanch the blood pouring from his nose.

Then he wailed for his mother. Kaden is 3; this was his first time riding a galloping sheep.

Mutton busting is the miniature equivalent of competitive bull riding. Children cling to sheep, and generally speaking, whoever stays on the longest wins. But even the most talented rider ends up on the arena floor. Playing make-believe rodeo with sheep has long been a pastime of rural children. But the sport has begun to move to wider, sometimes suburban, audiences and competitors.

Kaden was among the 20 or so children, most 3 to 6 years old, who competed in a mutton-busting event this summer put on by Wool Riders Only at the Arapahoe County Fair here in Aurora, a suburb of Denver.

"I think it builds character," said Meredith Templin, a nurse whose son, J.T., 6, had begged to compete. She lamented "this age where we sanitize our kids' hands every 30 seconds."

"I think that same mentality of parents being overprotective is the same as not wanting them to experience failure," she said.

Successfully riding sheep "did so much for his little ego. He was so proud of himself," she said of J.T., who came off his sheep quickly and took a hoof to the groin. He went back later for a second ride.

"We are teaching our kids that yes, you are going to fall. You can lose, too, and that can mean something," Ms. Templin said.

Kaden's brother Logan, 6, competed last year and returned "to rematch my enemy," he said. "The sheep." But as he was about to mount up, his chin trembled and he bolted into his mother's arms.

The sport's popularity seems based in such sentiments and a move toward embracing rough-and-tumble Western culture, according to participants.

No data exist for how many children participate nationally.

In 2005 the sport expanded from one event at the Colorado State Fair to 16 stops from Dallas, Texas, to Las Vegas, and a "World Finals," in Fresno, California.

Wool Riders Only estimated that this summer, 8,000 children would ride its sheep.

"It's scary to get on a live animal and ride down an arena," said Lisa Lawson, the director of operations for Tommy G. Productions, the parent company of Wool Riders Only. "When they do it, they feel like they are invincible."

Not all agree. Avery Martinez, 7, cried after getting a face full of arena dirt at the Arapahoe fair.

In an age of rubber-covered playgrounds, a sport in which a child can have 70 kilograms of sheep roll over him defies comprehension.

"Growing up on the East Coast, you don't see kids in any kind of danger, ever, and these parents are purposefully putting their kids on these crazy little sheep," said Stacey Berry, 25, a Massachusetts native visiting Jackson, Wyoming, for the summer.

"It looks cute," she said. "But I think it definitely borders on child abuse."

Mutton-busters disagree.

"It's not that we're out there to put our kids out there to get hurt," said Amy Wilson, 37, who helps run the Jackson Hole Rodeo.

"It's probably just like in the cities. Just like a kid going out for basketball and getting hurt playing basketball."

Even though her son Tipton, 7, broke an ankle at age 5 when a bolting sheep left him hanging from a gate by one leg, he still competes frequently.

One July day in Jackson, a 60-centimeter-tall cowboy careened out of the chute, somersaulted off the sheep and rose immediately, pumping tiny fists to wild applause.

At the Wool Riders Only in Aurora a week later, however, the air was at times soaked with sobs.

The more suburban a competition, the more tears, said Randy DiSanti, the event's announcer.

After Lachlan Murphy had a winning ride of 4.89 seconds that day in Aurora, all he could think about was the shiny medallion around his neck, even though his sheep had scraped him off on the arena's metal fence. "It's just a small sheep," he said, clutching his prize. "I just care that I won."

The New York Times

(China Daily 08/28/2011 page11)