|

REGIONAL> Culture Tourism

|

|

Day the earth stood still

By Victor Paul Borg (China Daily)

Updated: 2008-12-04 08:13

At Shaanxi's sprawling tumulus of Emperor Jingdi, the fourth Han (206 BC-AD 220) emperor, history did not stop when the emperor was entombed in 141 BC. History is once again being charted at the Hanyang Ling Museum, which was eulogized as an "outstanding achievement and a model for other relics protection projects" by Michael Petzet, chairperson of the International Council on Monuments and Sites. It's a living archeological museum, and the first in the world that is developing a new method for the preservation of relics in situ. "The tricky part is dealing with different substances in the pits, which include pottery, ceramics, metal, and wood fragments," explains Wang Baoping, deputy curator.

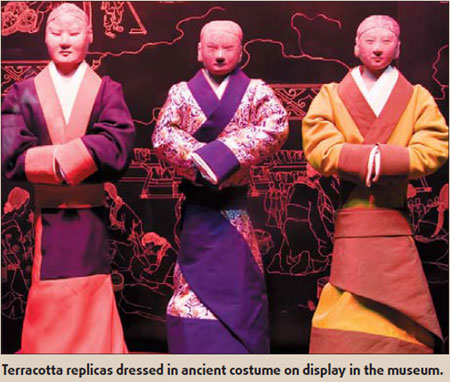

"The bulk of the material is clay and the importance with clay is to prevent it from cracking, yet metal requires a drier environment than most other stuff. "So we're still somewhat experimenting with the optimal climactic calibrations for all the different materials." Hanyang Ling Museum, located near Xi'an, which opened last year and cost 100 million yuan ($14.5 million) to construct, offers an experience that's more authentic and vivid than the more famous Terracotta Warriors Museum. In the latter the figures were reconstructed; in Hanyang Ling the relics are exhibited in the trenches as they were found. Visitors walk on the glass floor and peer down on the terracotta figures that constitute the phantom state apparatus of Jingdi's empire. It's like an entire ancient city that was buried and is now literally poking out of the earth. "By keeping the historical environment intact," Wang says, "it's like having a mirror on the state - the organization of the state is illustrated in the way the tumulus' pits were laid out." The massive tumulus, which is a mound of earth raised over graves, reveals a state that was efficient, organized and prosperous. Yet the emperors believed that they would transpose the entire state with them for perpetual rule in the afterlife, and it's estimated that Jingdi squandered 30 percent of the state's resources during his 17-year-reign to fulfill this fantasy. The scale is staggering: Each of the 81 pits that fan out from the central tomb, where Jingdi is interred, holds a different department of the government of the day. Trenches were dug and figures were created and placed in wooden tunnels, which were covered with earth again, and a grand sacrificial temple built on top. This temple has virtually disappeared. Eventually, the wood deteriorated and the earth caved in, and now Hanyang Ling Museum is built over the 10 pits that have been excavated. The figures, which are about half a meter tall, were made in molds. Their hands were added afterwards to fashion different poises, their faces were carved individually, and the figures dressed according to rank and role. No one was left behind: One pit holds the prison department with all the prisoners, and another holds the concubines that had fallen out of favor with the emperor. And the fantasy was so complete that even food wasn't left to chance. The kitchen department occupies two entire pits, containing stoves and urns of wheat, as well as rows of livestock, mostly pigs and cows and dogs, the preferred meat at a time when chicken and ducks were still new foods. Many of the figures are now missing their hands; others have their heads broken off; and some lie on their sides like fallen dominos, knocked over when the earth caved in. Looking down on the trenches, in the museum's dim and cold-white light (a light starved of UV for preservation purposes), the experience is surreal. It's like snooping in an esoteric place, a place that's forbidden to the living, a place that's even haunting in its eerie atmosphere. The collection seems to have an enigmatic life of its own - an artistic feat.

One can imagine how more realistic the figures looked before their costumes deteriorated. Today these figures are most naked. "The lowly slaves and servants weren't dressed and these are the lucky ones now, as their etched costumes are still intact," jokes Cheng Yanni, the museum's public relations officer. The museum is also educational. It was the first time in 15 years of writing about travel and culture that I learned about what archeologists call "organic relics". These are degradable remains - lances, swords, cloth, arrows and bows, and the wooden chariots - that are now at an advanced stage of decomposition. Most intact of these are the wooden chariots that were placed at the head of each tunnel or pit to symbolically lead the terracotta figures towards the emperor's tomb. All that remains of them now are outlines of the chariots and their riders flattened on the ground like raised carvings. Meanwhile, other pits have been explored in limited excavations to gain a fuller picture of the entire tumulus and the organization of the state during the flourish of the Han civilization. The site is huge spread over 12 sq km, containing the second mound of the empress as well as other "satellite tombs". In the exploratory excavations, the archeologists dug into the pits and some other tombs to have a peek at what's there, and then covered everything with earth again. "For the sake of preservation, we won't carry out any more full excavations at this stage," says Yan Xinzhi, deputy head of the museum's research section. "Once we find the optimum climate to stabilize the excavated relics, and once we gain enough knowledge in the preservation of post-excavation relics, then we'll start planning the complete excavation of the other pits. But for now the relics are more stable in their buried state."

(China Daily 12/04/2008 page19) |