Op-Ed Contributors

Debate: Urban congestion

(China Daily)

Updated: 2011-04-12 08:00

|

Large Medium Small |

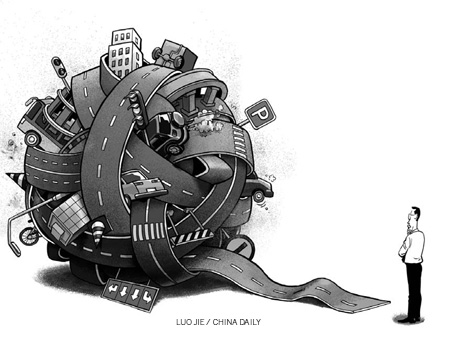

Too many cars on the roads are bringing cities to a standstill. Three experts explore the deeper issues involved and offer their solutions.

Murad Qureshi A.M.

Charge cars out of city center

Urban congestion was one of the serious issues discussed at the annual sessions of the National People's Congress and the Chinese People's Political Consultative Conference National Committee.

The Beijing municipal government has extended its transport measures since the 2008 Olympic Games by increasing public transport facilities.

But all of these initiatives have been overshadowed by the fast increase in the number of vehicles. Beijing is still home to almost 4.8 million cars and the number is rising fast.

The only solution to this problem is the continuous development of the city's public transport system along the lines already implemented by the authorities but with one addition, congestion charges, which ration road space through pricing. The congestion charge will bring the "cost" of an additional trip by car to the fore of car-owners' mind. And such a charge would be consistent with the Chinese government's focus on people-centric and scientific methods of development.

The introduction of such a program in London in 2002, has reduced the number of vehicles entering central London by 70,000 a day. It has produced real benefits for the city, not only by reducing key traffic pollutants, but also by improving public transport capacity and performance, and reducing road traffic casualties.

The geography of Beijing, with its several ring roads, makes it more suitable to impose congestion charges than London and other foreign cities that have already introduced such a program. A first congestion charge zone could be created within either the Second or Third Ring Road at the beginning. It can then be extended outward depending on the success of the program and public demand. This is a real advantage that Beijing has and it should use as a valuable tool to deal with traffic gridlock.

As in London, to win public support, the funds raised from the congestion charges would have to be reinvested into public transport, and some exemptions or at least a discount could be granted to residents within the charge zone.

The scheme could be put into operation quickly using simple technology like closed-circuit television cameras at entry points of the ring roads and using a database of car licenses.

So while local authorities consider all the policy options to improve traffic flow, including higher parking fees, building more roads and parking spaces, and limiting the use of government cars, they should not forget the tried and tested road pricing mechanisms that other cities have already implemented.

The author is chair of the London Assembly Environment Committee.

| 分享按钮 |