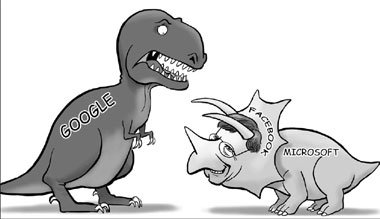

Facebook beams in, but Google still dominates

Updated: 2007-12-19 07:24

Never mind websites. Forget page views. They're so 2006. This was the year of Facebook. The social site, started in 2004 to organize college communities, was finally opened to the rest of us, and in the spring it was discovered en masse by media wonks (like me), who forced acquaintances into joining, using the evangelistic fervor of recent cult converts.

Then, in May, Facebook opened up to developers, who now were able to add applications to the service; already they've built 5,000. And in October, Microsoft beat Google to invest in the company at a valuation of $15 billion.

Worth it? I'd say yes. Facebook has 50 million active users (each worth $300, according to Microsoft, as opposed to $500 a year for a newspaper reader, according to Deutsche Bank). They are joined by 200,000 more daily, all of whom spend an average of 20 minutes every day inside.

But far more valuable than that is the realization of Facebook as a platform, on top of which we users organize our communities, and on top of which those developers are building venture-backed companies. Facebook analytics firm Adanomics tracks the supposed value of these applications, pegging the most popular, Top Friends, with 20 million installations, at $28m.

Facebook is answering the question every company should be asking: what would Google do? Google built a platform that enables others to build businesses; now so has Facebook. Indeed, 23-year-old Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg's ambition is to build the Google of people.

Yahoo would have been wise to have asked that question - WWGD? - years ago. Instead, it made itself into a classic, albeit digital, media company during six years under the leadership of CEO Terry Semel. That strategy ran out of gas and in June, when Yahoo fired Semel. Co-founder Jerry Yang took over and is now hinting at his new strategy - Yahoo as a platform.

At the same time, Yahoo's traffic numbers have been falling, but that's not because of dwindling popularity. It's because Yahoo's pages, like those of many sites now, are built on newer technologies - Flash, Ajax - which embed more content and functionality into a single view, reducing the clicks a user makes. That is why tracking service Nielsen decided this year to stop counting page views, which had been the universal measure of web popularity (but page views are now, remember, so 2006).

Measuring the Web is further complicated by the explosive growth this year of widgets: exportable modules of content and programming that are easy to add to a blog or MySpace page - YouTube videos, for example. Indeed, TV networks are counting on such open distribution.

NBC and Fox announced a new service to air their shows online; CBS began executing an "audience-network" strategy to have viewers share shows, and the BBC and Sky released new players. Yet at the same time, Viacom was suing YouTube parent Google for enabling piracy. All this reveals only that the very architecture of media distribution on the web is still very much in development. But the business model of internet media is becoming clearer. Google, Yahoo, Microsoft, and AOL have been in a race to buy advertising technologies - DoubleClick, aQuantive, Right Media, Tacoda - and no wonder, since it is apparent that the web will be supported by little more than adverts and ego.

In September, the New York Times ended its quixotic attempt to charge for content, TimesSelect, when it concluded that getting traffic and ads via Google search was a better business. This only fuelled speculation that new Wall Street Journal owner Rupert Murdoch will shut its tollbooth. The Economist has jumped its pay wall.

That would leave only FT.com trying to charge readers online as it does in print. So much for circulation revenue. All online is a freesheet. So if advertising is the lifeblood of the internet - and thus the future of all media - who controls it? Who wins? Who else? Google. By one calculation, it now has 40 percent market share of online advertising - a share growing faster than the industry.

So the constant calculation in media minds is whether Google is friend or enemy - as if there's really a choice. Belgian newspapers won a suit against Google News to take down their headlines, but by May, they had relented and allowed their news to return to Google. In a little-heralded but still significant shift, Google that same month included current and archived headlines, videos and photos in its reconstituted "universal search" results, giving new attention to media other than plain, old web pages (which - need more proof? - are so 2006).

Google also became a publisher. In August, it licensed and began serving complete wire-service articles. This only worried the newspapers that used to get that traffic.

While in the UK, the national brands keep squabbling as if in the playground over who's biggest online, in the US, newspapers should be so lucky. Tribune Company is going private, Belo and Scripps are hiving off their underperforming newspaper divisions and every month the industry's finances get worse.

Where does Google go next? The rumor is that it will release a phone or mobile operating system, overshadowing the launch of Apple's iPhone. Media will finally and truly go mobile.

For a preview of that, look no farther than the June US launch of the iPhone, where fanatics queuing overnight broadcast the scene live from webcams and wireless laptops and published about it in new microblogging platforms: Twitter, Pownce and status updates on, yes, Facebook. There's Facebook again. But note the one player that emerges in all of 2007's developments: Google. This may have been Facebook's year. But so far, it is still Google's century.

The author is a journalism professor at the City University of New York who blogs at buzzmachine.com The Guardian

(China Daily 12/19/2007 page11)

|

|

|

|

|

|