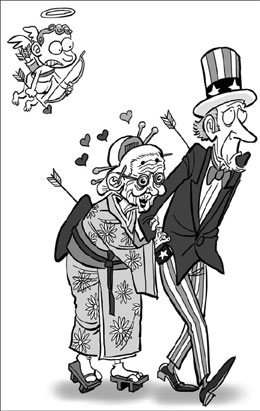

Fukuda's opportunity to boost US ties

Updated: 2007-11-13 07:03

Prime Minister Yasuo Fukuda, son of late Prime Minister Takeo Fukuda, will fly to the United States this month, three decades after his father's first summit in America. He will land in a country that has changed considerably in 30 years.

Most noticeably, in 1977, 220 million people lived in the US; today there are more than 300 million, a gain equivalent to nearly two-thirds of Japan's population. Japan, by contrast, has only grown by fewer than 14 million citizens since 1977. The Japanese population is now declining.

In 2037 there could be 380 million Americans, so Japan looks increasingly small and elderly compared with the US.

On the economic front, there was much anxiety about the Japanese industrial juggernaut in 1977. Americans feared that the "American Century" was giving way to the era of Japanese dominance. In 1979, Ezra Vogel of Harvard, in his "Japan as Number One", advised his fellow citizens to emulate Japan.

Thirty years later, however, America has demonstrated its primacy in the key technologies of our era, and there is less concern about US decline, although the long shadow of the subprime crisis is darkening this rosy picture.

Japan is now seen as lagging in the technological revolution headquartered in Silicon Valley and throughout the US. If Americans think that they will be dethroned economically, they fear China rather than Japan.

America's international position and its attitude to the outside world have also evolved. In 1977, the Cold War bound the US to its allies. The Soviet threat dictated the massive deployment of American forces in Eurasia backed by the political, economic, cultural, and military weight of US partners. In 2007, the Soviet Union is no more.

Therefore, Fukuda should expect to find an America that projects self-confidence and calm. But on the contrary, he will find the American psyche gripped by anxiety.

Americans, regardless of party affiliation, are still traumatized by the September 11 attacks. The suicide hijackings were an imaginative plot by foes with limited resources and unable to seriously threaten the US. But Americans believe a new "world war" had been declared.

In part due to this "post-traumatic stress disorder", which afflicts the American elite even more than the general public, US President George W. Bush was able to invade Iraq, hence precipitating a cascade of catastrophic events for the US.

Moreover, September 11 attacks fueled a Manichaean world view, best exemplified by the president's slogan: "You're either with us or against us."

Fukuda would be wrong to think that only Bush and his neo-conservative advocates have adopted this attitude. The acceptance by many American politicians of torture and their support for continuing the war in Iraq, or at best their tepid opposition to it, indicate that the president reflects the feelings of the American political and intellectual establishment of both parties.

One of the consequences of this situation is the replacement of "alliance" with the concept of the "coalition of the willing", which in plain English means that the US makes all decisions even if the allies contribute resources.

How do these developments make the Fukuda's visit different from that of his father? One positive change is that, partly due to the focus on China and the opening of Japan's markets, there is much less hostility to Japanese trade than there was in the 1970s. Therefore, the Japanese leader will not have to face a barrage of criticism from protectionist lobbies.

But due to the relative decline of Japan's population and the economic rise of the rest of East Asia, Japan now looks less important in American eyes. Additionally, the current American focus on "terror" and the unwillingness to listen to allies make the US a difficult partner to deal with.

As the Bush administration enters its twilight, Fukuda should use his time in Washington to get to better know members of Congress and the presidential candidates and to enlighten them about issues that are of importance to Japan.

It may not yield immediate results but could help lay the foundations for a better Japan-American relationship in the future.

The author is director of the Institute of Contemporary Japanese Studies at Temple University Japan Campus in Tokyo The Asahi Shimbun

(China Daily 11/13/2007 page11)

|

|

|

|

|

|